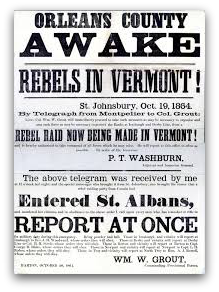

Did you know that a unit of Confederate soldiers invaded Vermont during the Civil War?

I didn't.

Did you know that a unit of Confederate soldiers invaded Vermont during the Civil War?

I didn't.

On October 15, 2014, I attended a talk by J. Kevin Graffagnino about the Confederate raid of St. Albans Vermont in October 1864.

In this post you will discover details about the St. Albans Raid as well as the valuable lesson the raid taught Graffagnino about researching and writing history.

Origins of Research

Since November 2008, J. Kevin Graffagnino has served as the Director of the William L. Clement Library at the University of Michigan. Prior to 2008, he held curatorial and administrative posts at the University of Vermont and the Historical Societies of Vermont, Wisconsin, and Kentucky.

As a native Vermonter, Graffagnino became interested in the St. Albans Raid as a child. His work at the University of Vermont and the Vermont Historical Society allowed him to conduct in-depth research about the raid from the Vermont point of view. His position at the Kentucky Historical Society gave him the opportunity to return to the raid and look at it from the Kentucky point of view.

The St. Alban’s Raid: An Overview

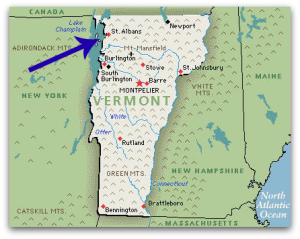

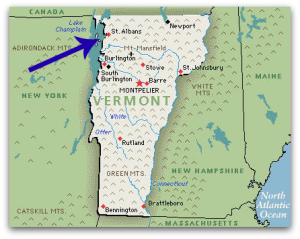

The St. Albans, Vermont raid stands as the northernmost military action during the Civil War.

The St. Albans, Vermont raid stands as the northernmost military action during the Civil War.

The raid took place on October 19, 1864 and it was led by a young Confederate calvary officer named Bennett Henderson Young.

The raid had strong Kentucky roots. In addition to Young, many of the Confederate soldiers who participated in the raid hailed from Kentucky.

Although the state government of Kentucky remained neutral throughout the war, many of its residents chose sides: Five times as many Kentuckians joined the Union Army than the Confederate Army.

In 1864, the Confederate Army sent 1st Lieutenant Bennett Young to Canada to reconnoiter the northern landscape of the U.S.

Canada did not take sides during the American Civil War. The country allowed civilians and soldiers from both the Union and the Confederacy to enter its borders to secure supplies or safety.

Young accepted his mission gladly. He wanted to punish New England for its role in the war and for the devastation its Union soldiers had wrought throughout the South. Young did not think it fair that nearly every community in the South lived in fear of wartime violence while most in the North lived without such fear, especially those in New England.

Young focused his attention on the northern borders of Vermont. Vermonters had been among the most vociferous opponents of slavery and the Confederacy.

In October 1864, Young met with Confederate leaders in Toronto. He told them that he intended to attack St. Albans, Vermont, a town in the northwest corner of the state.

Why St. Albans?

St. Albans made a perfect target for three reasons:

St. Albans made a perfect target for three reasons:

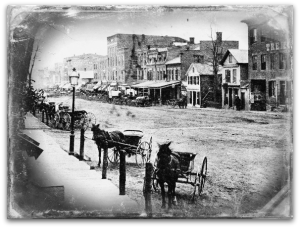

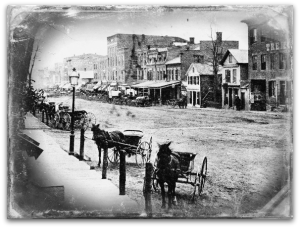

1. Railroad Hub: St Albans served as the headquarters for the Central Vermont Railroad. As a railroad hub, the residents of St. Albans were used to seeing out-of-town travelers. This fact would allow Young and his men to infiltrate the town with a minimum of suspicion.

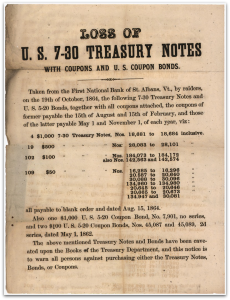

2. Money: As a railroad hub, St. Albans was a relatively prosperous community. Its three banks would have money in its vaults that Young and his men could secure and send back to the Confederacy.

The Confederate Army wanted Young to bring the horrors of the Civil War to New England. Young's attack was designed to unnerve the Yankees and make them live in fear that Confederate raiders might attack them at any moment. However, Young’s primary missions seems to have been to secure financial assistance for the Confederacy.

3. Location: Located in the northwest corner of the state, Young and his men could infiltrate St. Albans and make their way to the safety of Canada in short order.

The Raid

Twenty-two Confederate soldiers took part in the raid, including Young.

Twenty-two Confederate soldiers took part in the raid, including Young.

The twenty-two men arrived in St. Albans either alone or in pairs over several days. They stayed in different hotels as not to arouse suspicion. Their plan worked, no one in St. Albans suspected their plan.

The raid began at 3pm on October 19, 1864.

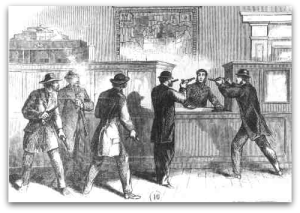

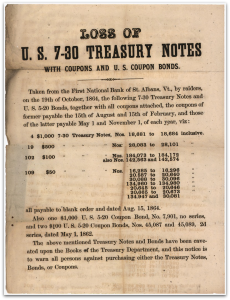

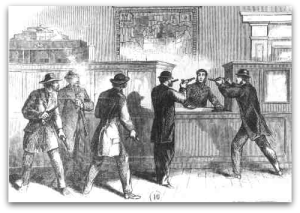

The Confederates divided into three different groups and each group entered a different town bank. In each bank, the Confederates raised their pistols and told the tellers and customers that they were Confederate soldiers who had come to take St. Albans and its money for the Confederacy.

The raid lasted 25-30 minutes.

After they robbed the banks, the soldiers rounded up all the horses in town. The rest of the St. Albans residents became aware of what was happening as the Confederates gathered the horses. The residents marched to the town square with their odd assortment of firearms.

A furious firefight ensued.

The civilians shot three of the raiders. The Confederates killed one civilian, an out-of-town visitor by the name of Elias Morrison. Ironically, Morrison had been a Confederate sympathizer.

After the firefight, Young and his men mounted their horses and galloped out of town. As they rode away they threw bottles of "Greek Fire" onto the sides of St. Albans buildings. Fortunately for the residents, the fire mostly smoldered. The only building claimed by Young's fire was an outhouse.

Flight into Canada

Young and his men galloped away with approximately $227,000 in their saddlebags.

Not long after crossing into Canada, Canadian police captured 14 of the raiders and about $90,000 of the stolen money. A Vermont posse apprehended Young.

Upon his arrest, Young claimed combatant status. The Vermonters didn’t care. They threw Young into a wagon and started back to the United States. However, before they made it across the border, Canadian police officers stopped the party and took Young into custody.

Upon his arrest, Young claimed combatant status. The Vermonters didn’t care. They threw Young into a wagon and started back to the United States. However, before they made it across the border, Canadian police officers stopped the party and took Young into custody.

Although the Canadians promised to return Young and his men to the Vermonters the next day, they did not. They opted to keep them in country to face an extradition trial.

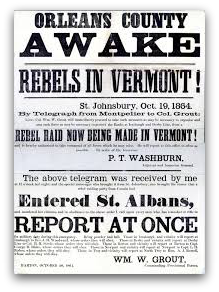

The Confederates may have failed at burning down St. Albans, but they succeeded in creating a feeling of panic and worry throughout Vermont. Rumors spread like wildfire throughout the state that Confederates were attacking towns and cities such as Burlington.

Vermonters interrogated hobos and any other unknown persons who entered their town. The state government formed a calvary unit to patrol its borders; the only available men to serve in it were invalid soldiers.

Meanwhile, the Canadians shipped the Confederates to Montreal where a judge would determine whether or not to extradite them back to the United States. In mid-December, the judge decided that he did not have jurisdiction to decide the case. He released Young and his men.

U.S. officials had them rearrested in short order. They asked the Canadians to hear charges of larceny, Young and his men had robbed individuals, an extraditable offense.

The Vermonters did not have much luck in Canada.

By late March 1865, the Canadian courts ruled that the raiders were not in fact eligible for extradition. Graffagnino pointed out that this decision could have been a bit of revenge for how the Vermonters supported the 1838 Patriot rebels against the Canadian government. Whatever the reason, the Canadians set Young and his men free.

Brief Epilogue

The Confederates made away with a large portion of the $227,000 that they stole from the St. Albans banks.

The Confederates made away with a large portion of the $227,000 that they stole from the St. Albans banks.

The banks and their account holders lost all but 1/3rd of the money, which the Canadian authorities returned to the town.

Some of the stolen bank notes made their way to the Confederate capital in Richmond, Virginia, but the money arrived too late to do much good. The war ended in April 1865.

Graffagnino and other scholars of the raid suspect that many of the raiders used their proceeds to start new businesses and careers at the end of the war. Although Graffagnino did not give a specific statistic, he related that many of the raiders returned to Kentucky and the South where they became bankers and prominent businessmen.

Between 1865 and 1868, Young wandered around Canada and Ireland; the United States had a bounty on his head. In 1868, he made his way back to Kentucky, settled in Louisville, and opened a successful law practice. He died in 1919 at 75 years old. Today the citizens of Louisville remember him as a soldier, philanthropist and gentlemen.

Lesson From the Raid

Graffagnino closed his hour-long lecture by asking “so what?”

So what has the St. Albans Raid taught him about history and conducting research?

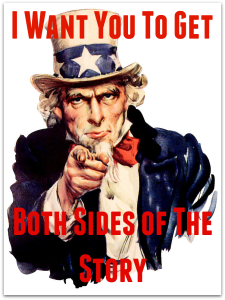

Graffagnino responded that researching the raid taught him how important it is to look at both sides of the story.

During his early career in Vermont, he only looked at the Vermont side of the story. Although he had collected a great many details about the raid, those details became richer during his time in Kentucky.

While working for the Kentucky Historical Society, Graffagnino learned more about Young, his men, and how the southerners portrayed the raid.

Understanding more about Young, his men, and their Confederate views gave Graffagnino a new appreciation for the raid and a fuller picture of what happened.

Conclusion

I admit that I attended Graffagnino’s lecture because I was interested in the content.

As a native New Englander with roots in both Boston and New Hampshire, I had no idea that the Confederates attacked Vermont. This surprising detail prompted me to step out of my historical comfort zone and find out more.

However, I am grateful that Graffagnino related his point about the importance of understanding both sides of the story when you research and write history. It seems like an obvious point, but it is one I have struggled with.

However, I am grateful that Graffagnino related his point about the importance of understanding both sides of the story when you research and write history. It seems like an obvious point, but it is one I have struggled with.

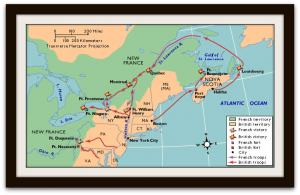

I have spent so much time researching the people of Albany that I almost feel insulted when I read an account by someone who does not understand how the fur trade worked, what it was like for the Albanians to live on the frontier, or to have their city used as a military base throughout each of the four wars for empire.

When I wrote my dissertation, my advisor sent back a few chapter drafts with calls for me to be more sympathetic to outside points of view. I am glad I took his advice.

For example, when I researched the Earl of Loudoun’s quartering practices during the French and Indian War from his point of view, I found that Loudoun disliked billeting his men in the Albanians houses and that he did all in his power to lessen the inconvenience. This was not something that I had read about in the Albanians’ accounts of the affair.

Today, I try to be more even-handed when I research and write about history. It was nice to hear that Graffagnino has also had to work at this part of his craft too. It was also nice to hear him voice a reminder to all of the historians and history enthusiasts in the audience that they should research and write about the past fairly.

Share Your Story

How do you avoid over sympathizing with your historical subjects?