On Sunday, August 24, 2014, Tim and I toured the city of Luzern, Switzerland.

Situated on the edge of the Vierwaldstättersee (Lake Luzern), with a panoramic view of the Alps, Luzern stands as the tourism capital of Switzerland.

On Sunday, August 24, 2014, Tim and I toured the city of Luzern, Switzerland.

Situated on the edge of the Vierwaldstättersee (Lake Luzern), with a panoramic view of the Alps, Luzern stands as the tourism capital of Switzerland.

Luzern used to be on the “Grand Tour” route of all persons making their way through Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Brief History of Luzern

The history of Luzern dates back to about 750 when a group of Benedictine monks founded the Monastery of St. Leodegar. A fishing village grew around the monastery.

Luzern had become as a bustling trade center by the 13th century. The village sat amid the Gotthard Pass trade route and many traders passed through and settled in Luzern as a result.

King Rudolph I von Habsburg brought Luzern and Switzerland under his rule in 1290. Unhappy with Habsburg rule, Luzern joined three other Swiss cantons (similar to counties) and formed the “eternal” Swiss Confederacy known as the Eidgenossenschaft in 1332. Three other cantons joined this alliance and together they pulled free of Austrian rule in 1386.

The Swiss Confederacy lasted until around 1520. While most of the other cantons became Protestant, Luzern remained mostly Catholic.

The Swiss saw a change in governance again in 1798 when Napoleon marched into Switzerland; the French brought democracy to the country.

Kapellbrücke

The Kapellbrücke or Chapel Bridge stands as one of the most iconic sites in Luzern.

The Kapellbrücke or Chapel Bridge stands as one of the most iconic sites in Luzern.

Built during the first half of the 14th century, the bridge connected the town’s medieval fortifications. It also stood as a defensive structure. Built at an angle, the “window” openings facing the lake are smaller than its inland facing windows. The smaller openings provided defenders with more cover.

Next to the bridge stands the Wasserturm or Water Tower, which the people of Luzern built around 1300.

During the 17th century, artists decorated the bridge with paintings that depicted the history of the town as well as two patron saints.

The bridge you see and walk on today is not 100% original. In 1993, a pleasure boat moored under the bridge caught fire and set the bridge ablaze. The people of Luzern rebuilt the fire-damaged sections of the bridge, but they could not replace the paintings the fire destroyed. Therefore, only a few of the 17th-century paintings remain.

Reuss River Weir System

Luzern sits at the place where the Reuss River flows out of Lake Luzern on its way into the Rhine.

Lake Luzern receives most of its water from snowmelt. Therefore, the lake can fluctuate in depth depending upon how much rain north-central Switzerland receives and how fast the winter snow melts off the nearby Alps.

Prior to the 19th century, lakeside towns experienced flooding when lots of rain or fast melting snow flooded the lake. In the 19th century, the people of Luzern devised an extendable dam called the Nadelwehr or Spiked Weir, that allows them to maintain the water level of the lake by controlling its flow into the Reuss.

Each spring, the weir operators remove spikes from the weir to increase the flow of water out of Lake Luzern. When the water level of the lake drops in the summer, they replace the spikes to slow its flow into the Reuss. The weir operators close the weir entirely during the winter months to keep the water level high enough for the boats that ply the lake.

Spreuerbrücke

Like the Chapel Bridge, the wooden Spreuerbrücke (known in English as the Mill Bridge) dates back to the 13th century. “Spreu” manes chaff and this bridge connected the town to its mills.

Like the Chapel Bridge, the wooden Spreuerbrücke (known in English as the Mill Bridge) dates back to the 13th century. “Spreu” manes chaff and this bridge connected the town to its mills.

As many as 10 mills used to line the edge of the Reuss River.

Artists in the 17th century also decorated the Mill Bridge with paintings, all of which are visible overhead as you walk across the bridge. When you reach the halfway point you will find a little chapel, which the town built during the 16th century.

Today, volunteers decorate the chapel according to the season.

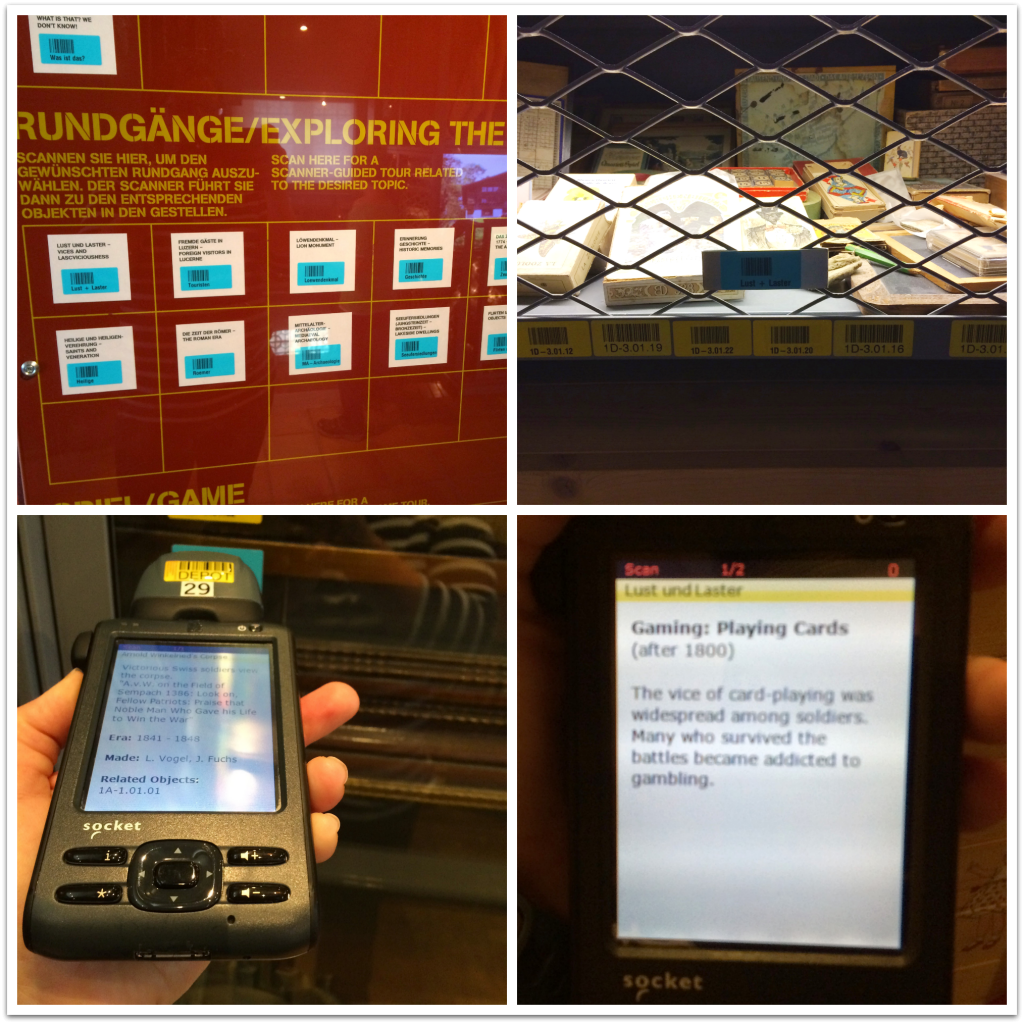

The Depot History Museum and its Novel History Interpretation Method

After Tim and I walked across the bridges and along the Reuss we visited the Historisches Museum of Luzern.

The museum is located in one of the oldest buildings in Luzern and it bears the nickname “The Depot” as the townspeople have placed all of their historical odds and ends inside of it.

Walking into the museum feels like walking into a warehouse. Spread out over three floors, the Depot displays its massive collections of paintings, toys, clothing, clocks, weapons, coins, pottery, and even toilets on industrial shelving units protected with glass or chicken-wire enclosures.

Given the sheer size and depth of this collection, the Depot provides each visitor with a barcode scanner. Each item within its collection has a barcode. When you come to an item you want to learn about, you scan the barcode and information about the object appears on your handheld scanner.

Upon presenting you with your scanner, the museum docent presents you with two options for how to view the museum's collections: 1. Walk around the museum on your own and scan objects that interests you. 2. Scan one of the blue tags before you head upstairs and have the scanner guide you through a themed tour of its collections.

Upon presenting you with your scanner, the museum docent presents you with two options for how to view the museum's collections: 1. Walk around the museum on your own and scan objects that interests you. 2. Scan one of the blue tags before you head upstairs and have the scanner guide you through a themed tour of its collections.

Initially, Tim and I attempted the first option, we scanned any item that piqued our interest. However, we became overwhelmed before we reached the first floor.

Few of the objects we scanned shared a relationship with one another. Not being well-versed in the history of Switzerland we lacked the context needed to place the disparate items we scanned in our minds or to connect them with one another.

Within 5-10 minutes we gave up our self-guided approach and returned to the ground floor to select a themed tour.

The museum presented several different themed tour options. One tour offered to guide visitors through items related to maps and geography. Another offered a medieval archaeological tour. Tim and I picked the “Lust & Vice” tour.

Our scanner directed us to objects that fit within the theme of “Lust & Vice.” Each time we scanned a blue tag associated with our tour a bit of narrative appeared on our scanner screens. These narratives provided us with the historical context that we had missed during our initial do-it-ourselves approach. For example, in front of a shelf filled with different playing cards our scanners informed us that “the vice of card-playing was widespread among soldiers. Many who survived battles became addicted to gambling.”

With that said, some of the narratives stretched an object's relationship to the theme of “Lust & Vice." One tag led us to a display of different police caps. The blurb on our screens informed us that although police caps changed in style over time they always projected a "racy style" or something to that effect.

I applaud the museum curator's efforts at trying to explain and connect the Depot's bric-a-brac. Although the narratives on the “Lust & Vice” tour sometimes left me wanting more information, or scratching my head as to how certain objects had made this themed tour, the connections the scanner made between the objects proved a valiant effort to help visitors make sense of the hodgepodge collection.

Conclusions

The Historisches Museum of Luzern is the first place where I have encountered a total reliance on a barcode scanner system of interpretation. I have seen other museums place QR codes on exhibit panels that allow visitors to receive additional information about the object through their smartphones.

The Historisches Museum of Luzern is the first place where I have encountered a total reliance on a barcode scanner system of interpretation. I have seen other museums place QR codes on exhibit panels that allow visitors to receive additional information about the object through their smartphones.

After my visit to the Depot, I thought about how much I enjoyed being able to select how I wanted to learn about the museum’s collections. The plethora of proffered tours allowed me to choose my own museum adventure.

The feeling and freedom involved in choosing how I wanted to learn about the history of Luzern made my experience more fun. It also ensured that I chose a topic that interested me.

Additionally, the use of scanners made the tour more fun. After I finished reading about one group of objects, my scanner told me which tag I needed to look for next. This instruction provided a treasure hunt-like experience. Not to mention, that the act of scanning the tags provided a certain amount of fun too. My observations of the other museum visitors told me that they felt the same way, especially the kids who raced around the museum’s three floors in search of their next tag.

I would love to see more museums in the United States (and elsewhere) adopt Luzern’s “create-your-own-adventure” approach. However, this approach really needs to include themed tour options that will guide visitors through the ways they can connect the various objects to each other and to the larger interpretive themes of the museum.

I believe that the interpretive model offered in Luzern would appeal to museums that are looking to attract more visitors. In our age of flashy technological gadgets and shortened attention spans, the “choose-your-own-adventure” model offers a fantastic approach that well suits our present-day culture.

What Do You Think?

What Do You Think?

What do you think about the “choose-your-own-adventure” model of museum interpretation? Have you seen it applied anywhere else?