How do we fund digital history communications projects?

This question has occupied my mind for quite some time.

How do we fund digital history communications projects?

This question has occupied my mind for quite some time.

Many historians appreciate how Ben Franklin’s World provides history lovers with access to the world of scholarly history. They see the value in generating and stimulating interest in professional historians’ work. However, few have ideas about how to fund and institutionalize projects like Ben Franklin’s World.

Digital history communication is seen as necessary, but non-traditional scholarship. Presently, there is no place for it within either academic or public history institutions.

Those of us who work in digital history communication and communications perform work that everyone wants done, but no one wants to pay for. This has to change.

Engaging the public will be what rescues history and other humanities fields from their present period of crisis.

So how do we raise funds to do our work until we have the proof institutions need to support our scholarship?

In this post, you will discover the four traditional methods for monetizing a digital communications project. I will also reveal why I have chosen to begin funding Ben Franklin’s World with crowdfunding.

4 Methods of Monetizing a Digital Media Project

There are four, proven methods for monetizing digital communications projects.

1. Pre-sell ad space: You approach potential advertisers and pre-sell ad space on your project.

This method works well if you have an established reputation for producing high-quality media.

2. Advertisements: You sell space on your program to people who want to sell something to your audience.

In general, advertisers purchase ad space on audio and video podcasts using the CPM (Cost Per Mille/Thousand) model. For every one thousand downloads or views your podcast garners an advertiser will pay you $2-$50 per thousand.

The amount an advertiser pays depends upon whether their ad will be native (read by the host) and where it will be placed. There are three options for ad placement: Pre-roll: before the main program content; Mid-roll: in the middle of the program; Post-roll: at the end of the program.

Unless you have a program that generates millions of downloads or views, you can’t make a living or support a project using this model. This is why some podcasters supplement the CPM model by including clickable advertisements on their websites. This strategy works well if you have a high-traffic website.

Other podcasters avoid the CPM model and craft their own advertisement deals. They create a media kit that lists their digital assets (podcast, social media followers, e-mail list subscribers, website traffic, poll data showing the demographics of their audience and how engaged it is) and present custom packages to potential advertisers. The presented packages have a set cost and advertisers often have several options to choose from as each package comes with different levels of ad placement, guaranteed social shares/promotion, affiliate opportunities and commissions.

3. Products and Services: Program hosts create products and services that audience members can purchase.

The most successful digital media producers offer products and services to their audience. Products and services include one-on-one or group consulting, webinars, eCourses, eBooks, private mastermind groups, affiliate products, and access to bonus or old content.

WTF host Marc Maron offers his latest 50 episodes for free and charges $3.99 per month for access to his older episodes.

4. Crowdfunding: Ask your audience for support.

You set up a campaign and ask your audience to fund your work in exchange for continued high-quality content, swag, promises of no ads, bonus features, and access to you.

You set up a campaign and ask your audience to fund your work in exchange for continued high-quality content, swag, promises of no ads, bonus features, and access to you.

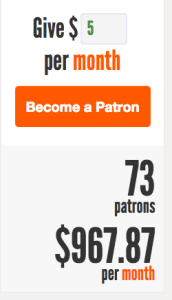

Sites like Patreon and Podbean offer content producers the infrastructure they need to ask audience members for regular, monthly contributions. Think Kickstarter but without a campaign time limit.

These sites make money by charging transaction fees and by taking a cut of what you make. For example, Patreon takes 5 percent of what you raise plus you pay another 4-6 percent in credit card transaction fees or a fee for payment transfers if a supporter opts to pay you via bank account transfer.

After considering these four options, I have decided to begin funding Ben Franklin’s World with crowdfunding.

Why Crowdfunding? Why Now?

Some people have a car payment, I have a podcast payment.

Producing and promoting a high-quality digital history communications project costs money.

When I started Ben Franklin’s World I made a promise to my partner Tim (the benefactor of my digital history projects), that if I succeeded in creating a successful platform, I would find a way to make it self-supporting.

Ben Franklin’s World has been successful and now it’s time to honor my promise.

My first option for monetizing Ben Franklin’s World has always been to ask my audience for support. They are the people who benefit most from my efforts, which means they also appreciate the value of my work.

I have launched the Ben Franklin’s World crowdfunding campaign, which I call the Ben Franklin’s World Movement. Ben Franklin’s World is part of the movement to help bring history back to the forefront of the public mind. The campaign asks my audience to participate in this movement in both financial and non-financial ways.

The How-To of the Ben Franklin’s World Movement Campaign

My campaign includes a video, non-financial support requests, and packages that ask for monthly, annual, or name-your-own financial support.

I am hosting the campaign on the Ben Franklin’s World website using a customizable LeadPages LeadPage; LeadPages is marketing software I purchased so I could offer a text-to-opt-in option for my listeners (text BFWORLD to 33444 to receive the show notes for each podcast episode in your inbox).[1]

LeadPages connects with PayPal, which will process funders' payments. I created custom PayPal buttons for each sponsorship package linked in my LeadPage. These buttons will place the correct amounts in my funders’ carts.

I am keeping track of donors by using MailChimp’s integration with PayPal. MailChimp will automatically log each new donor on a separate email list and send them a thank you note.

I chose to bypass sites like Patreon because I wanted to host the campaign on my website and I did not want to pay the 5 percent monthly and additional transaction fees.

As Patreon and like sites process payments through PayPal, my campaign strategy cuts out the middleman. Without the “middleman,” I maximize the amount I receive from my listeners’ donations. This is important to me as I have plans to expand the educational resources offered by Ben Franklin’s World and I ideas for other digital history communications projects.

Circumventing sites like Patreon has two drawbacks: First, sites like Patreon make it easy to set-up a campaign.

My desire to save 5 percent per month, plus additional transaction fees, required me to invest time into thinking about how I could recreate their campaign system with services I already pay for.

Second, my bypass means my campaign lacks a few crowdfunding specific options, like a total amount raised widget.

As I want to be transparent about the monies I raise, I will start issuing monthly earnings reports in November. I will place these reports on the BFWorld website and I may also send these reports to my funders via e-mail.

Conclusion

Will crowdfunding fully fund my digital history project?

I don’t know. I am hopeful it will cover my production costs.

I look forward to posting more about how the campaign works as a funding model for digital history projects when I have data to report.

[1] Please note that the LeadPages link is an affiliate link. I purchased the LeadPages template I am using for my campaign. LeadPages offers many free templates. I had to purchase a template that included the video, package, and button options I wanted because I adapted the software to fit an unintended purpose.