Between June 11 and June 14, 2014, I attended the 35th Annual Conference on New York State History.

Between June 11 and June 14, 2014, I attended the 35th Annual Conference on New York State History.

In addition to presenting a paper entitled “Memory, Community, Loyalty: Albany, New York during the American Revolution, 1763-1776,” I attended the conference as an interested scholar of New York State History.

Here is a recap I wrote of an interesting panel called “Mormonism and the Empire State.”

The post appeared on John Fea’s blog “The Way of Improvement Leads Home” on Thursday June 19, 2014.

On Friday, June 13, 2014, Gerrit Dirkmaat (Joseph Smith Papers Project) and Michael Hubbard MacKay (Brigham Young University) presented “Mormonism and the Empire State,” a panel at the 35th Annual Conference on New York State History. Together these scholars analyzed Joseph Smith’s interaction with the scholarly and print culture of 1830s New York to demonstrate the connection Mormonism has with the state.

Michael Hubbard MacKay argued that Mormonism was “ensconced” in New York culture because Joseph Smith connected the religion with the state’s scholarly community. The Mormon tradition holds that in 1823, an angel visited Smith and directed him to a stone box buried on a hill near his Manchester, New York home. Inside the box, Smith found golden plates. The plates contained many cuneiform-looking characters. As the angel instructed Smith not to show the tablets to anyone, Smith kept the plates hidden and transcribed their symbols on to paper.

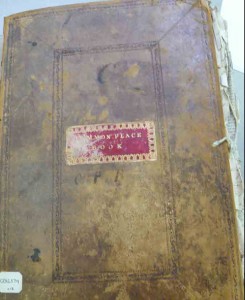

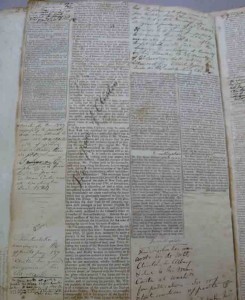

The symbols on the golden plates formed the basis of the Book of Mormon. However, neither Smith nor anyone else could understand what the Book of Mormon said until they deciphered the characters. Smith sought translational assistance from scholars around New York State.

A letter from Joseph Knight Sr. shows that Smith wanted a learned man to translate the symbols from the plates. Smith’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, confirms this idea when she wrote that her son transcribed the “characters Alphabetically and sen[t] them to all the learned men that he could find and ask[ed] them for the translation of the same.” Smith worked with his friend and follower Martin Harris of Palmyra, New York to find a scholar who could help them.