I don't get SnapChat. Why would you spend time creating content that people can only access for a limited period of time?

I shared this musing on Twitter and enjoyed exchanges that culminated in the fact that I'm old.

I don't get SnapChat. Why would you spend time creating content that people can only access for a limited period of time?

I shared this musing on Twitter and enjoyed exchanges that culminated in the fact that I'm old.

I may be a first-year millennial (I did in fact graduate high school in the year 2000), but I'm a member of the "Oregon Trail" part of the generation. The part that embraces new technology and still appreciates what came before it. I'm also a member of a profession that still lauds the book as the ultimate form of scholarly production. Books vary in quality, but they all take time to produce.

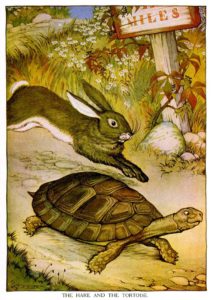

In the world I grew up in and the world I work in, it takes time and energy to produce content and preserve memories. These ideas and experiences shape the way I think about digital content and how it should be produced. They also make me a tortoise living and running in a hare's world.

The "Hare Approach" to Content Creation

In comparison, "real" millennials and "post-millennials" have grown up using smartphones, tablets, apps, and hardware, like Snap's Spectacles, to easily create digital content. As a childhood friend pointed out, "now, basic content creation is nearly effortless." You can create content and preserve a memory in seconds.

In comparison, "real" millennials and "post-millennials" have grown up using smartphones, tablets, apps, and hardware, like Snap's Spectacles, to easily create digital content. As a childhood friend pointed out, "now, basic content creation is nearly effortless." You can create content and preserve a memory in seconds.

We live in a world full of digital content, but most of it's created quickly and it's not very good: bad blog posts, blurry photos, mundane status updates, and shaky videos. This mediocre content clogs the internet and means something only to those who created it and to those who understand the context of its creation.

Thinking about SnapChat within the context that content creation should be easy and effortless is when SnapChat started to make sense to me: The social app caters to people who want to create fast, effortless content. And thinking about SnapChat in this light has allowed me to appreciate how Snap may be doing our digital world a great service by making low-quality, hastily created content available only for a short period of time. Less clutter means more space for the great stuff to shine.

But what does the idea of creating fast, easy content on-the-go mean for the future of content creation? Has my belief that historians and other digital content producers should expend effort to produce high-quality, well thought out content become outmoded?

Should I morph into a hare?

I don't think so, at least not yet.

The "Tortoise Approach" To Content Creation

If my ideas about content creation were outmoded then Amazon, Netflix, HBO, and now Apple wouldn't be investing HUGE sums of money in the production and curation of high-quality, niche programs like Game of Thrones.

If my ideas about content creation were outmoded then Amazon, Netflix, HBO, and now Apple wouldn't be investing HUGE sums of money in the production and curation of high-quality, niche programs like Game of Thrones.

All of these companies are producing high-quality shows unlike anything you can see on a traditional network to draw people to their subscription-based, digital content libraries. And if you're like me, you enjoy programs like Game of Thrones more than the programs on network television because of their production value. They involve many characters, have huge story arcs, and contain great special effects (hello, real-looking dragons & dire wolves). These high-quality shows also aren't beholden to the traditional time clock of network television-- episodes don't have to adhere to 30- and 60-minute time slots.

And premium digital networks aren't the only ones investing time and money into highly-produced content. Masterpiece Theater produces shows of similar quality for PBS. Think Downton Abbey, Victoria, and Poldark. They have less special effects than a show like Game of Thrones, but they all have high-quality production.

It's also interesting to compare the types of content networks are producing. HBO produces content like Game of Thrones and TrueBlood to appeal to fantasy lovers. People accustomed to good stories and who have a track record of paying for merchandise, books, games, and content. Masterpiece Theater's main goal is to drive people to support public broadcasting. They mainly produce mysteries and history-inspired programs. People who like history tend to enjoy culture, are civic-minded, and they have a track record of donating money to support the work of organizations like PBS and NPR.

Video-based content companies and companies that service digital video apps aren't the only companies investing in high-quality, digital content. So are traditional news outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and NPR.

The New York Times and The Washington Post have publicly declared that they are redoubling their efforts to produce well-researched, long-form articles to differentiate themselves from other news outlets. They're banking on the fact that high-quality content will drive ad sales and subscriptions. They've also started audio divisions to lead people to their print content and to advertise their areas of expertise-- The Washington Post specializes in political podcasts; The New York Times produces podcasts about culture and they just released The Daily, a podcast that focuses on a big news story and leads you to its printed or digital newspaper.

NPR is also investing money in high-quality podcasts. The powerhouse networks that feed a lot of content to the national NPR network-- WBUR (Boston), WNYC (New York City), and WBEZ (Chicago)-- all have podcast and mobile divisions to produce apps like NPR One and great shows like Modern Love, Death, Sex, & Money, and Serial. Further, NPR-trained talent has started a whole host of new venture-funded podcast companies like Gimlet and Pineapple Street Media.

These new digital audio companies were founded to produce high-quality, on-demand audio content. Their funding models are based on three ideas:

1. High-quality, intellectually-driven content attracts listeners that advertisers will pay a premium to get access to because host-read podcast ads aren't yet regulated by the FCC, which means ads don't have to sound like ads, and the listeners the intellectually-driven content attracts tend to have disposable incomes.

2. If you have enough high-quality content, listeners will pay to access a back catalog like a subscription network. (These paid-subscription models are just starting to appear and will become more visible as these networks add to their content catalogs.)

3. Big companies recognize the value of high-quality content and are willing to pay networks to create custom content for them--like Open for Business by eBay, produced by Gimlet, and GE's podcast The Message, produced by Panoply.

Why the Tortoise Will Win in History Content Production

Tortoises like me live in a hare's world. We look slow and outmoded in the way we produce digital content. But our goals are different from those of the hare.

Tortoises like me live in a hare's world. We look slow and outmoded in the way we produce digital content. But our goals are different from those of the hare.

In my case, I want to create content that resonates with people, that creates wide awareness about history, and that cultivates a sentiment within society that history and the work historians do is worth supporting. I'm, in fact, running a tortoise's race. So my ideas aren't outmoded, they're timely and they make sense.

I believe there is a place for the hare's content. Photos and images created quickly with smartphones are fun to produce and share. However, the hare's content won't build a lasting audience. Within the last decade we've seen Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram content producers who quickly built massive audiences only to watch those audiences dwindle and leave as new apps and social networks came out and interests changed. The quick and easy content they produced entertained only for a limited time.

History has staying power. People will always be interested in history because it helps us grapple with the big, existential questions of who we are and how we came to be who we are. This is why historians have always invested time and energy into producing content that lasts: books, articles, museum exhibits. And this tried-and-true method of investing time and effort in the content we produce should also be our approach in the digital world.

We should embrace the hare, borrow everything from its technological toolbox that will help us communicate history, and then adapt these tools to amplify our work. Because just like in the analog world that came before the digital world, quality work will rise to the top, be consumed by more people over time, and will last-- just like tortoises, which live an average of 200 years versus hares, which live an average of 5.5 years.