What kind of historian are you?

Over the last week, I have been asked this question three or four times. It's a question the irks me because I don’t quite understand why we continue to label our colleagues.

What kind of historian are you?

Over the last week, I have been asked this question three or four times. It's a question the irks me because I don’t quite understand why we continue to label our colleagues.

In this post, you will discover the various labels we have for historians, why many historians continue to label their colleagues, and why we should do away with most professional labels.

Overview of Historian Label Use

In graduate school, I learned that historians classify themselves by the period and geography they study: medievalist, early modern Europeanist, South Americanist, early Americanist, 19th-century Americanist, etc.

Classification by geography and period makes sense. Historians all study history, but by stating our period and geography in a quick and efficient way we allow our colleagues to know our area(s) of expertise.

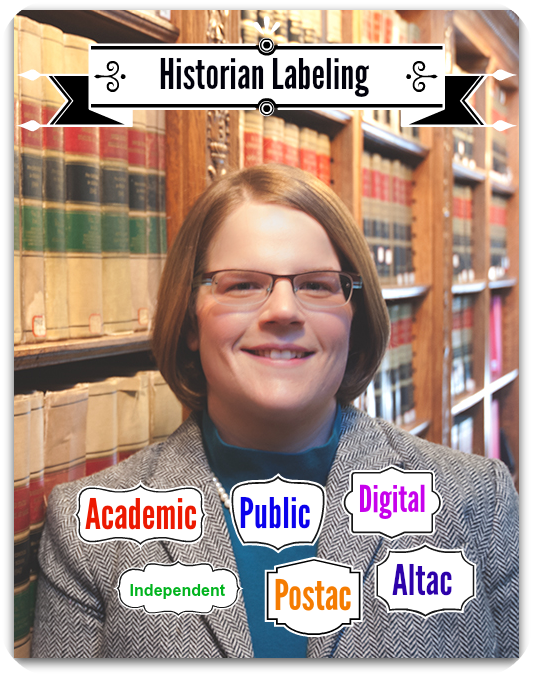

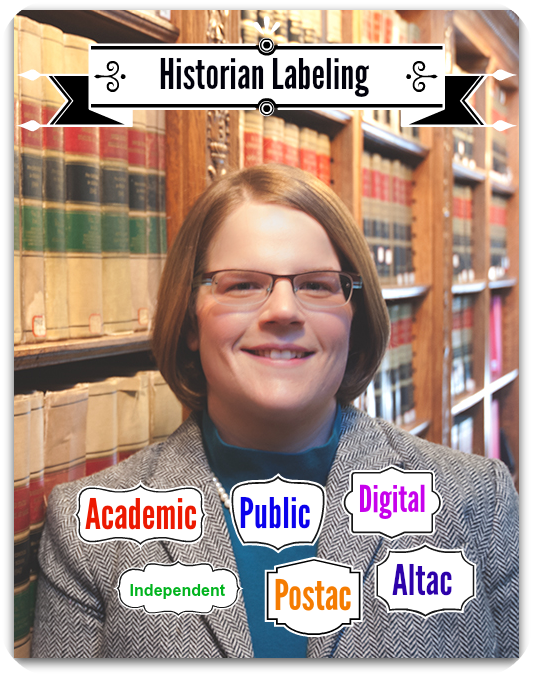

Graduate school also introduced me to the fact that many historians like to classify themselves in terms of affiliation and profession: Academic, public, independent, and amateur.

After graduation, I discovered that professional labels did not stop with academic, public, independent, or amateur. Some historians also use the labels of digital historian, digital humanist, post-academic (also spelled post-ac or postac), and alternative-academic (alt-ac or altac) to define themselves.

I understand why many historians use labels: They provide a short code for who professional historians should take seriously. However, these labels of affiliation and profession are fraught with stereotypes. They are also restrictive, exclusive, and obsolete.

Below I offer my basic (and I am sure incomplete) definitions of each historian label. These definitions should help you better understand why I find them restrictive, exclusionary, and outdated.

Basic Definitions for Historian Labels

Academic: An historian with a Ph.D. in history and a tenure track position as a professor at a university of college. Academic historians teach, conduct research, write-up their research, and use this written work to set and participate in debates and conversations about history.

Public: Historians who convey history to the public. Public historians work at public and private institutions such as historical societies, museums, national parks, libraries, and archives. Sometimes they hold PhDs, often they have a masters degree. Public historians have expertise in developing exhibits and interpretive programs about history for the general public. They may also specialize in providing assistance to historians and history lovers who want to find information about history.

Public: Historians who convey history to the public. Public historians work at public and private institutions such as historical societies, museums, national parks, libraries, and archives. Sometimes they hold PhDs, often they have a masters degree. Public historians have expertise in developing exhibits and interpretive programs about history for the general public. They may also specialize in providing assistance to historians and history lovers who want to find information about history.

Independent: An unaffiliated historian. Someone who self-funds their research. These historians can be trained professionals or journalists-turned-historians. They may also be genealogists who perform genealogical research as professionals and who seek recognition as members of the historical profession.

Amateur: Hobbyist historians. These historians have a passion for history and have followed their passion into the world of archival research. They have no formal training and they pursue their work when they have time. They may write short articles for local newspapers or online publications. Sometimes they write full-length books.

Digital: An historian who works with and incorporates new technologies into their research and historical interpretation methods. They may conduct interdisciplinary work and might consider themselves as digital humanists. Some digital historians create computer programs to extract information from big data sets.

Postac: An academically-trained historian who has left the academy. Postac historians might work as independent historians or they might have left the profession altogether.

Altac: An academically-trained historian who has pursued a different career path within academia. They might head a special department or initiative or assist with or perform administrative work. Many altac historians teach history courses when time and opportunity allow.

Thoughts on Historian Labels

With the exception of the period and geography labels, I believe that the 21st century has rendered the above affiliation and profession labels obsolete.

Too many historians use affiliation and profession labels as a short code to make a quick assessment about an historian’s work without taking the time to get to know an unknown colleague. They assume that if an historian they meet does not have the “right” label then they don’t have the right kind of training or don't use professional research and interpretive methods.

Too many historians use affiliation and profession labels as a short code to make a quick assessment about an historian’s work without taking the time to get to know an unknown colleague. They assume that if an historian they meet does not have the “right” label then they don’t have the right kind of training or don't use professional research and interpretive methods.

Historian labels have created divisions within our profession; I have heard both academic and public historians use the term “academic” and “public” as pejoratives to describe a fellow historian.

I have also seen, and experienced, affiliated colleagues shrug off independent historians because of their unaffiliated status. The sentiment “there-must-be-something-wrong-with-you-or-your-work if you are unaffiliated" underlies many of these affiliated historians’ dismissals of their independent colleagues.

We all know that there are numerous well-qualified historians who lack affiliation because the recent recession and an overproduction of graduate degrees has reduced the number of available jobs for historians who wish to work in academia or for public and private institutions.

However, it’s not just professional snobbery that renders historian labels obsolete: it’s how the labels limit the range of our work.

Present-day historians wear many hats and cultivate diverse skill sets to prosper in the tight job market and further their professional work.

I know plenty of academic historians who have a passion for public outreach and plenty of public historians who cross over into the academic realm by conducting high-quality, historical research and conveying what they find in scholarly publications.

There are altac historians who create interesting digital projects and independent historians who work with public and academic history institutions as consultants. Furthermore, there are amateur historians who have a deep passion and know more about certain subjects than those who teach those topics in college classrooms.

No one label can possibly fit most historians because most of us have multiple historical and professional interests.

Furthermore, labels also exclude a number of professional historians because their job descriptions do not fit into any of the above labels. Take documentary editors, for example. These historians have a specialized skill set and job functions that place them in numerous categories: academic, public, altac, postac, and digital. However, using multiple labels is cumbersome and the practice fails to produce a quick short code for their work.

Conclusion

It’s time that historians stop obsessing over professional labels.

We are losing the funding fight with STEM subjects in part because our profession can become consumed with internal fighting over professional labels and the boundaries of work that they supposedly create.

Labels breed professional snobbery and inhibit profession-wide collaboration.

All historians need to be engaged in a quest to reassert the relevancy of history. Therefore it shouldn’t matter what field you study or where you work. We should help instead of exclude and fight with each other.

Discarding labels won’t be easy.

When was the last time you attended a professional seminar, conference, or event that didn’t have you fix an affiliation on your name tag or state your affiliation at the start of the event?

I don’t like labels and I dislike it when my colleagues try to affix a label to me, but I occasionally use them. And yes, I am guilty of using labels to make quick and unfair assessments about unknown colleagues.

But I will do better. I will make a conscious effort to discard labels.

The next time I attend a history seminar or attend a conference that requires me to place a label on my name tag, I will say that I am an historian of early America. Because this is the only meaningful and comprehensive label that describes what kind of historian I am.

What Do You Think?

What Do You Think?

What do you think about professional labels?

Last week, Michael Hattem of The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History interviewed me about Ben Franklin's World and my alternate career path.

Here's an excerpt:

Last week, Michael Hattem of The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History interviewed me about Ben Franklin's World and my alternate career path.

Here's an excerpt: