How much money did the merchants of Albany, New York realize from the French and Indian War?

In this post you will discover the exciting new information I found during a recent research trip to the American Antiquarian Society and why I am rethinking French and Indian War profits.

How much money did the merchants of Albany, New York realize from the French and Indian War?

In this post you will discover the exciting new information I found during a recent research trip to the American Antiquarian Society and why I am rethinking French and Indian War profits.

Charges of Great Profits

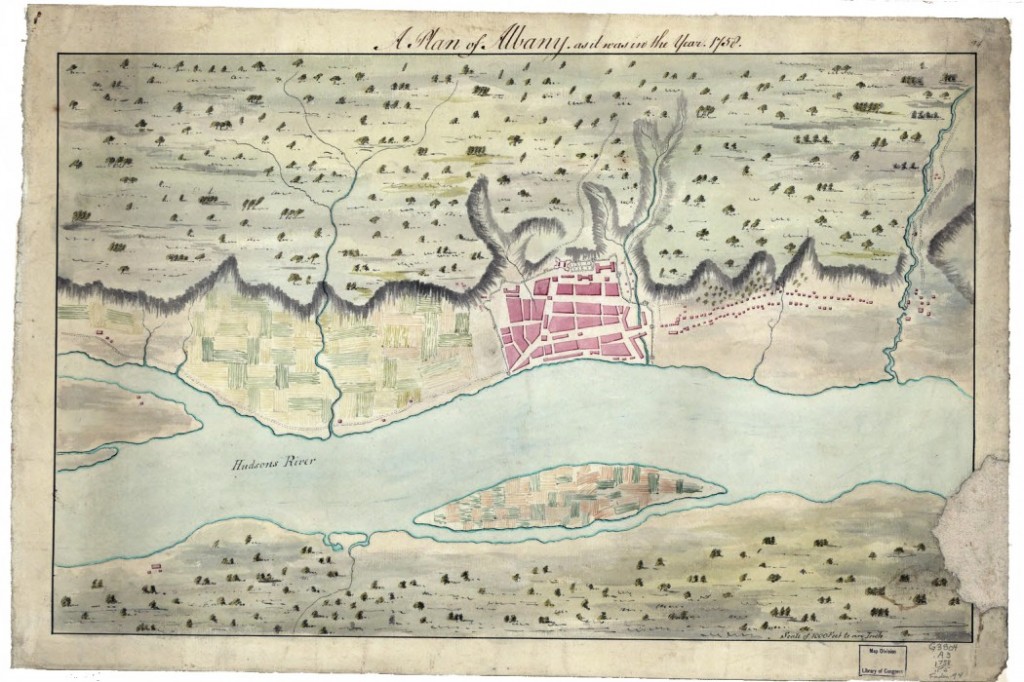

New England merchants and soldiers, New York City merchants, and traders from abroad complained that the merchants of Albany had discriminated against them during the French and Indian War (1754-1763).

They charged the Albanians with excessive taxation and with creating an unwelcome environment. They also claimed that the merchants of Albany had reaped great profits from the war.

Secondary sources about the war contextualize and moderate these assertions. The secondary sources claim that the profits of the war began in London and trickled down to merchants in major American seaports like Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City before they reached inland cities like Albany.

The Business of Military Supply

The War Department requisitioned supplies and contracted with large London mercantile firms to provide them. In turn, the London firms engaged large American houses, like those owned by the DeLanceys of New York City and the Franks of Philadelphia, to receive, acquire, and disperse those provisions.

Often provisions contracts between London merchants and large American firms charged American merchants with acquiring perishable foodstuffs closer to the front. Sometimes the American firms engaged trusted contacts in settlements closer to the front lines to fulfill their agreements for perishables and to deliver London-sent goods to locally stationed commissaries. More often, they sent factors (usually junior partners) inland to facilitate their military contracts.

Available records make it impossible to quantify how much profit Albany merchants made during the French and Indian War.

Available records make it impossible to quantify how much profit Albany merchants made during the French and Indian War.

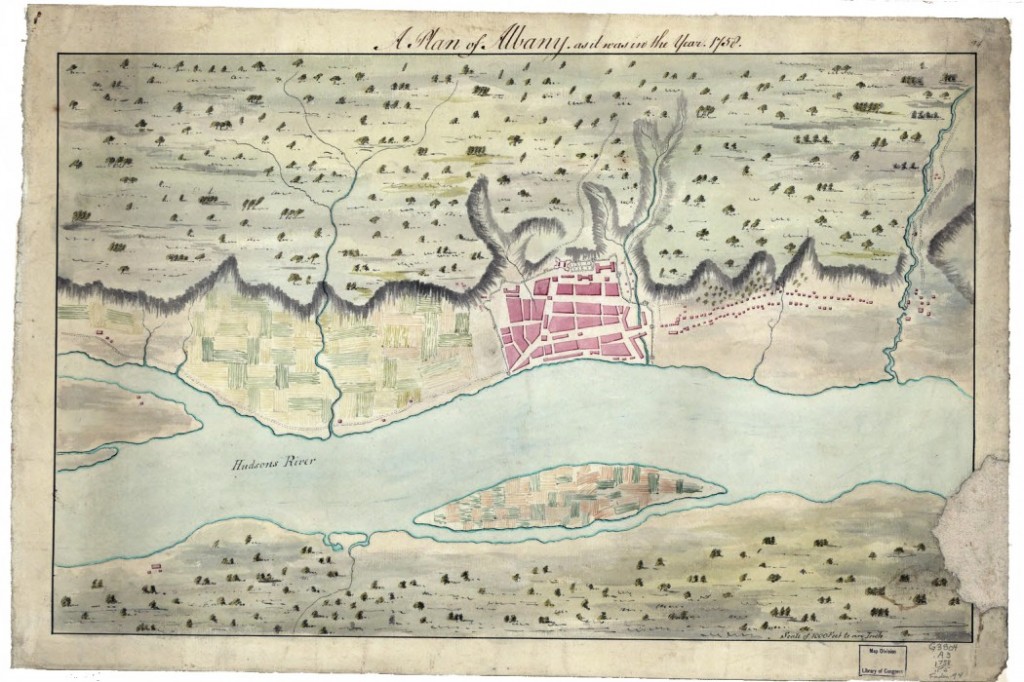

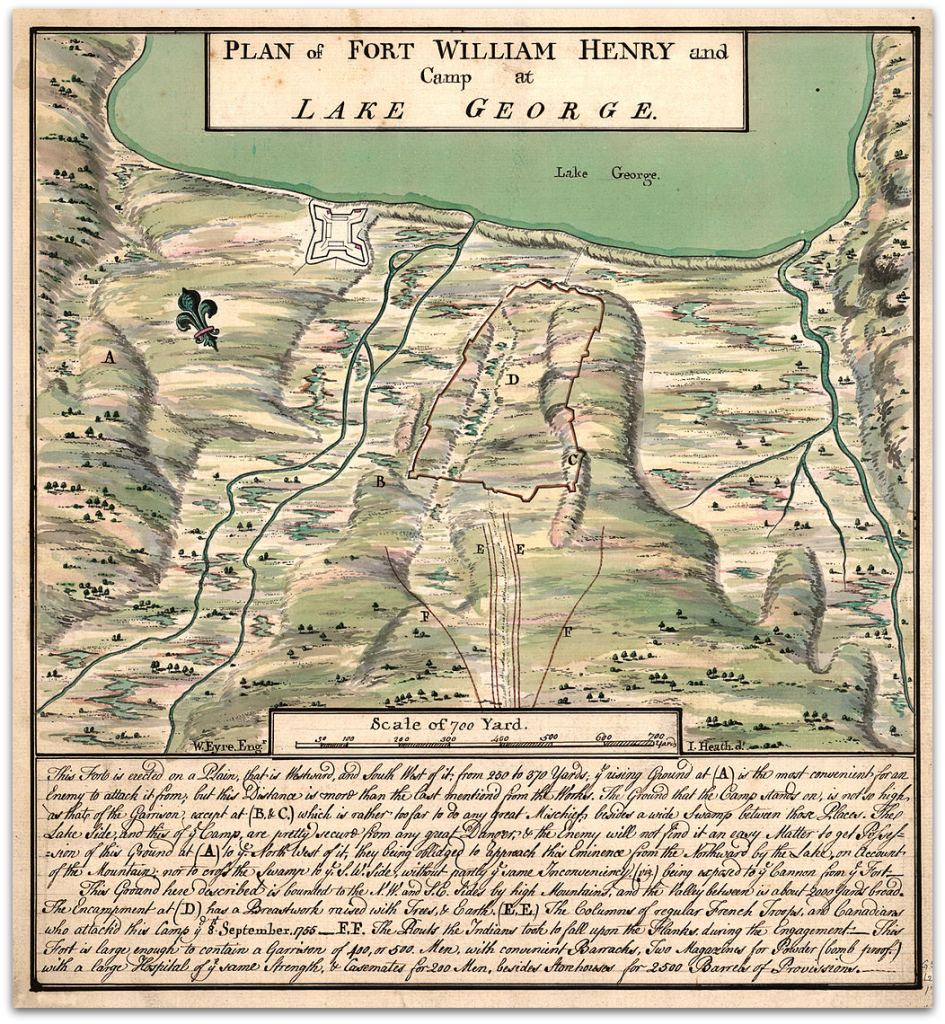

Scattered documents show goods that some Albany merchants imported during the war. They also provide a glimpse of how much money the British Army spent in Albany to hire laborers, build bateaus, and provide other services. For example, in 1758, John Bradstreet needed 1,500 bateaus for the campaign against Ticonderoga. He infused £19,251:15:1/2 into the Albany economy by purchasing lumber, naval stores, and labor to build them.

How Much Did Albany Merchants Profit from the War?

Although available documents make it impossible to quantify how much Albanian merchants profited from the war, I have never doubted that some of them must have made a fortune.

However, a recent research trip to the American Antiquarian Society has prompted me to rethink my assumption. My trip to the AAS put me into contact with the letterbooks of Cornelis Cuyler, one of Albany’s wealthiest merchants.

Cornelis Cuyler made his money the old-fashioned way: inheritance, marriage, and business.

The eldest surviving son of Johannes Cuyler and Elsie Ten Broeck, Cuyler inherited both the family fur trade business and the elite status that came with the “ancient” Albany-based names of Cuyler and Ten Broeck. He became a third-generation fur trader, a trade that required him to interact with Mohawk and other Haudenosaunee or Iroquois peoples and travel into “Indian Country.”

Cuyler’s efforts and keen sense of the trade enhanced the family business and wealth, as did his marriage to Catharina Schuyler, the youngest daughter of Albany Mayor Johannes Schuyler and Elsie Staats Wendell Schuyler. (Schuyler, Wendell, and Staats are also surnames that belonged to elite Albany families.)

Cuyler’s efforts and keen sense of the trade enhanced the family business and wealth, as did his marriage to Catharina Schuyler, the youngest daughter of Albany Mayor Johannes Schuyler and Elsie Staats Wendell Schuyler. (Schuyler, Wendell, and Staats are also surnames that belonged to elite Albany families.)

Cuyler’s letterbooks provide ample evidence that he understood the fur trade and how to leverage his familial connections to trade in Albany and abroad; Cuyler knew how to buy (or trade) for furs, where and when to sell those furs (London or Amsterdam), and how to use the proceeds to purchase English and Dutch manufactured goods, or goods from the West Indies, who to contact to smuggle the Dutch goods into New York, and how to sell them at a profit in Albany.

Cuyler's letterbooks reveal that knowledgeable and established Albany merchants profited early in the war, but not after 1756.

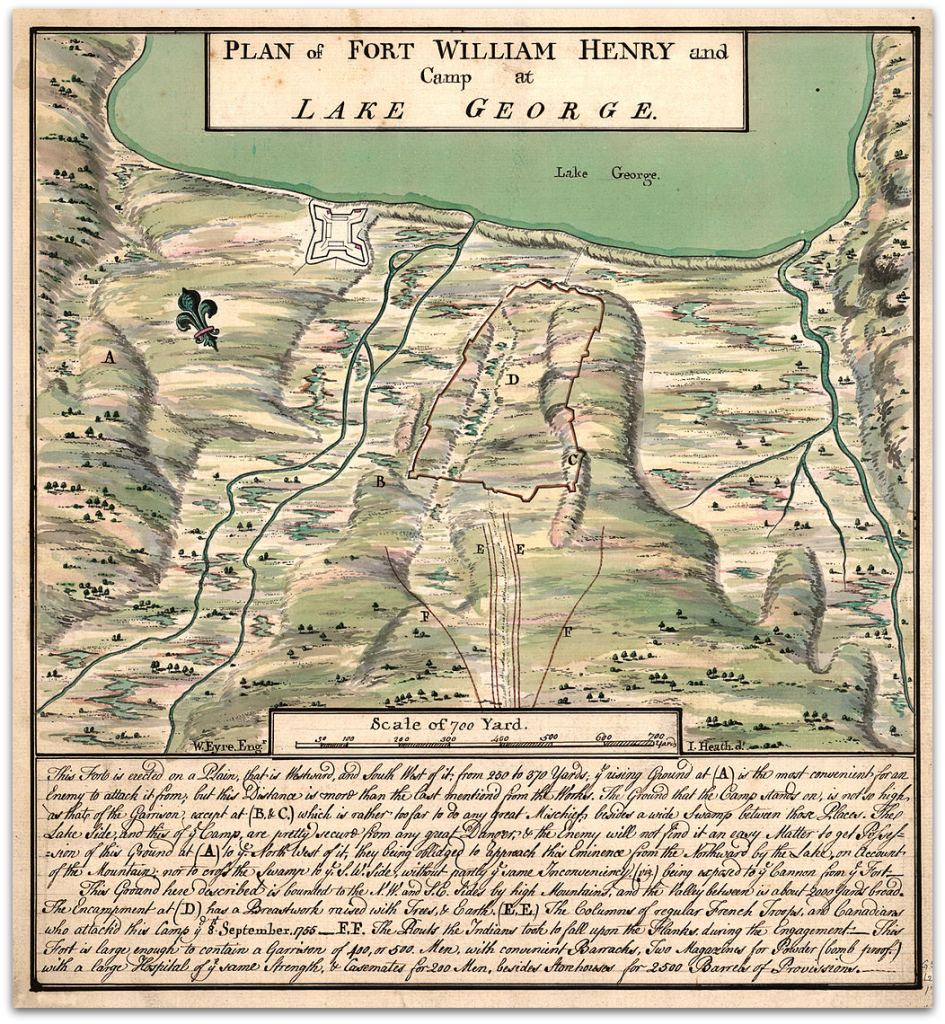

In 1755, Cuyler purchased £100* worth of textiles, clothing, and metal goods to sell to British soldiers, colonial militiamen, or for use in the fur trade. Additionally, Cuyler discussed how he provisioned sick and wounded soldiers at Lake George, advanced money to representatives from various colonial war committees, and rented property to an out-of-town commissary.

I have not been able to locate Cuyler’s account books, but his letters show someone with few complaints until April 1757.

I have not been able to locate Cuyler’s account books, but his letters show someone with few complaints until April 1757.

On April 7, 1757, Cuyler wrote to his relative and factor in Boston, Jacob Wendell, “Every thing here is @ Present Stagnated.”

On the same day, he wrote to his eldest son Philip in New York City, “Everything here is Stagnated with us” and that all of the profit went “to the People from New York” who “Supplys the Regulars Troups.” Cuyler commented on the unfairness of the situation: the merchants of New York City made all the money “& we have all the Burdon. I have at present 6 men & an Officer Billeted upon me that is Besides the Officers Servant.”

Cuyler’s letters reflect frustration at the military supply system. Unable to make money in military supply, Cuyler and his son invested in risky privateering ventures. Cuyler disliked the risk associated with privateering, but he invested in one or two ships anyway; he held a 1/16th share of one privateer.

Conclusions

Cornelis Cuyler’s letterbooks provide evidence that the people of Albany profited from the war, but not necessarily to the extent that the accounts of New England and foreign merchants have led us to believe.

Albany merchants who wanted to get rich from the war invested in risky schemes like privateering because partnerships with New York City firms did not always work out.

Cuyler’s letters indicate that more often than not New York City merchants like the DeLanceys removed Albany merchants from the profit chain. They hired New York City men or sent their sons to handle the supply contracts.

Cuyler’s letterbooks represent just one source. I plan to look for others, but few account and letterbooks from Albany during the French and Indian War period remain thanks to time and the New York Capitol fire of 1911.

Still, Cuyler’s letters provide insight into why the Albanians resorted to enforcing the ancient practice of “freedoms” (a license that all persons not born in Albany had to purchase in order to conduct trade in the city) and why they petitioned the New York Assembly, Governor, and Council to enact a law that would permit them to tax transient merchants. (The New York Assembly, Governor, and Council passed the requested law.)

Cuyler's letterbooks also suggest that the Albanians guarded their chances to profit because the trials and tribulations brought on by living in close proximity to British Regulars year-round caused many Albanians to feel entitled when it came to profiting from the war. Any profits the Albanians earned came at the price of hosting and housing the British Army.

*MeasuringWorth.com relates that £100 sterling in 1755 was worth approximately $13,500 in 2013.

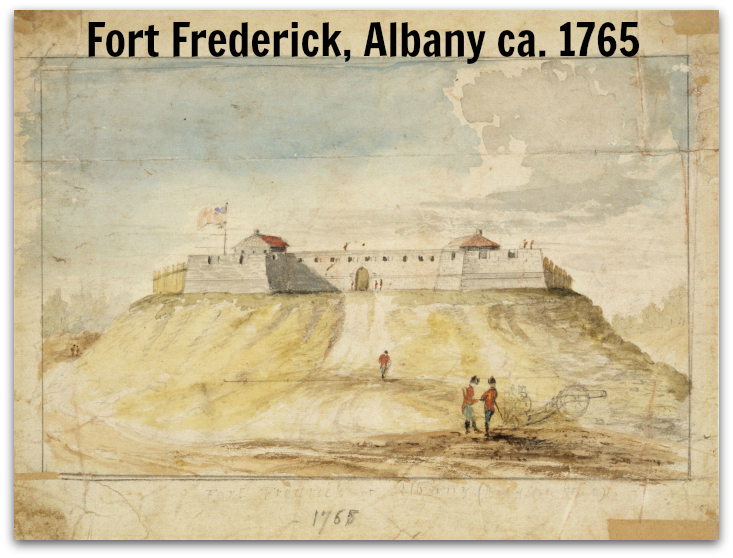

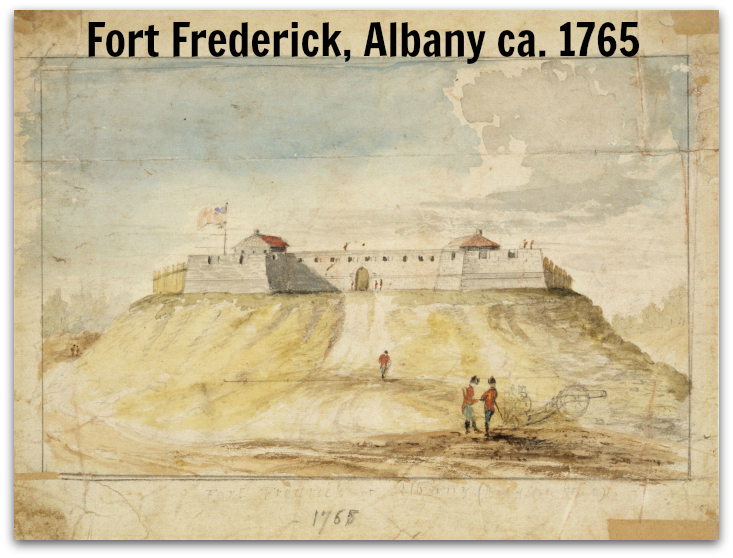

Drawing of Fort Frederick courtesy of the Albany Institute of History & Art

The editors of the Journal of Early American History have published my article "Trade, Diplomacy, and American Independence: Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co. and the Business of Trade During the Confederation Era" in their latest edition.

I came across the papers of Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co. during my volunteer work at the Albany Institute of History and Art. In exchange for building a finding aid for the Ten Eyck/Gansevoort Papers (MG2), I had the opportunity to be the first scholar to look at the collection. I had hoped that the papers would contain information for my book project AMERICA'S FIRST GATEWAY: ALBANY, NEW YORK AND THE MAKING OF AMERICA, 1614-1830. Instead, the collection led me to my second book project: The Articles of Confederation.

The editors of the Journal of Early American History have published my article "Trade, Diplomacy, and American Independence: Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co. and the Business of Trade During the Confederation Era" in their latest edition.

I came across the papers of Cuyler, Gansevoort & Co. during my volunteer work at the Albany Institute of History and Art. In exchange for building a finding aid for the Ten Eyck/Gansevoort Papers (MG2), I had the opportunity to be the first scholar to look at the collection. I had hoped that the papers would contain information for my book project AMERICA'S FIRST GATEWAY: ALBANY, NEW YORK AND THE MAKING OF AMERICA, 1614-1830. Instead, the collection led me to my second book project: The Articles of Confederation.

I have not been able to locate Cuyler’s account books, but his letters show someone with few complaints until April 1757.

I have not been able to locate Cuyler’s account books, but his letters show someone with few complaints until April 1757.