Historians need to stop thinking about the tenure track as the only way and as the only measure of success within the profession. The profession would instantly help improve the job market for historians by improving its ability to help students at all levels of historical training recognize and discuss their unique and valuable skill set outside of the academy. It also needs to stop treating employment within the tenure track as the only “true” job market for historians and as the only measure of success.

Meet the New Ben Franklin's World Team Member

I’m pleased to announce that Christopher Jones has joined the Ben Franklin’s World team for the summer.

Christopher is a contributing blogger to Religion in American History, a founding member of The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History, and a soon-to-be doctoral graduate of the College of William & Mary.

I’m pleased to announce that Christopher Jones has joined the Ben Franklin’s World team for the summer.

Christopher is a contributing blogger to Religion in American History, a founding member of The Junto: A Group Blog on Early American History, and a soon-to-be doctoral graduate of the College of William & Mary.

Christopher will be helping me research two projects I have in development: A new, occasional format for Ben Franklin’s World and a new podcast that I would like to launch before the end of 2016. Both of these projects will benefit from his expertise in early American history and our ability to bounce ideas off of one another.

As Ben Franklin’s World approaches its second anniversary on October 7, I’ve been thinking about ways to add fresh perspectives and formats to the show. I have several ideas about ways to accomplish these feats, but as most of my time goes to producing the podcast, I lack the time to research these ideas thoroughly. Christopher will add more productive hours to my day. Additionally, as one of my goals is to add fresh perspectives to the show, it will be good to have someone on the team who thinks differently than I do to help add different viewpoints.

As Ben Franklin’s World approaches its second anniversary on October 7, I’ve been thinking about ways to add fresh perspectives and formats to the show. I have several ideas about ways to accomplish these feats, but as most of my time goes to producing the podcast, I lack the time to research these ideas thoroughly. Christopher will add more productive hours to my day. Additionally, as one of my goals is to add fresh perspectives to the show, it will be good to have someone on the team who thinks differently than I do to help add different viewpoints.

Thinking about digital media networks and how I can add to the format of Ben Franklin’s World sparked an idea for a new, short-form podcast that I would like to launch before the end of 2016. I’m not ready to divulge too many details, but like Ben Franklin’s World its mission will be to help connect people who have an interest in history to the work of professional historians. Unlike Ben Franklin’s World, it won’t be limited to early American history. (Fear not my early Americanist colleagues, I’m an early Americanist for life. I have a Trello board filled with ideas for more early American history-centric long-form podcasts.)

Now that you know what we will be working on this summer, what will you be working on?

A Traditional Historian in a Digital World: How I Write History for Podcasts

At NCPH 2016, someone asked the panelists of "Drafting History for the Digital Public" how we acquired the digital skills to work on our various projects. My answer: My historical training drives my digital work.

For the next three days, colleagues asked me about my response and since the conference more questions have found their way into my inbox. Most of the questions inquire about the “specialized” and “technical” training I use to write history for digital audio.

At NCPH 2016, someone asked the panelists of "Drafting History for the Digital Public" how we acquired the digital skills to work on our various projects. My answer: My historical training drives my digital work.

For the next three days, colleagues asked me about my response and since the conference more questions have found their way into my inbox. Most of the questions inquire about the “specialized” and “technical” training I use to write history for digital audio.

Confession: I am a traditional historian using traditional historical skills to work in an accessible digital media.

Ben Franklin's World represents an interview-driven form of narrative history. The end product of each episode may be a digital audio file, but the historian’s traditional tools—research, analysis, interpretation, and writing—give birth to each episode.

In this post, you will take a behind-the-scenes tour of Ben Franklin's World to see how I use my traditional historical training to produce its digital audio content.

Research

Like most history books and journal articles, Ben Franklin's World episodes begin with questions and research.

Listeners determine most episode topics. They e-mail, tweet, Facebook message, and verbally request topics such as the American Revolution, Everyday Life, the Constitutional Convention, and George Rogers Clark. It’s helpful to know what aspects of early American history listeners want to explore, but as we learned in graduate school, what makes history fascinating is asking the right questions of broad topics. It’s up to me to come up with the historical questions each episode will explore.

How do I know what questions to ask and investigate? I research. I look at the historiography to see what arguments and interpretations of the broad topic exist and which historians to contact. After I schedule a guest, I prepare for each interview by reading their work or researching their project/historic site.

Analysis

Analysis plays a role in all stages of episode production. I use the historian’s ability to analyze information when I research episode topics, read guest books and articles, prepare interview questions, interview guests, edit episodes, and when I write episode intros, outros, and show notes.

When I read a book for the show, I read it for information and structure and reference both with the historiography. I facilitate this analysis by taking notes on argument, interesting facts, the historical questions the author asks, their answers to those questions, and how the historian structured their narrative as I read. Upon finishing a book, I review my notes and use my knowledge of the historiography to contextualize the information they contain. This comparison and contextualization allows me to determine what information we should highlight in the interview, how to ask questions that get at the desired information, and how to sequence the questions so that the questions and answers tell a coherent story about the topic of the episode.

It’s the same type of analysis we do when we study for comps, explore the secondary source literature for course reading assignments and lectures, and consider as we determine how to write up our research projects for books and articles.

Interpretation

Ben Franklin’s World seeks to create advocates for history and historical research by generating wide, public awareness about the work of professional historians. The project generates awareness by offering accessible interpretations of the modern historiography of early America.

Each episode contains two types of interpretation: The guest historian’s interpretation of the historical record and my interpretation of their interpretation.

My interpretation comes through in the questions I ask and how I edit each episode. Each question reflects information I want to highlight for listeners. The order in which I ask questions reflects the sequence of how I think listeners should explore or think about historical people, events, and themes.

Historians rely on this type of interpretation every time they offer a lecture, build an exhibit, lead a tour, write a synthesis narrative, or edit a collection of scholarly essays.

Writing

I cannot overstate the role good writing and editing skills have played in the success of Ben Franklin’s World. The reason that most Ben Franklin’s World episodes convey tight, coherent mini-narratives about early American history is my graduate advisor took the time to teach me how to write and edit my work.

Every episode of Ben Franklin’s World relies on a scripted structure and undergoes at least three rounds of editing.

Guest historians offer natural, unscripted responses just as I offer unscripted commentary and follow-up questions. However, I script out the intro and outro for each episode as well as 50 to 80 percent of the questions you hear me ask. This is not to say I read the scripts verbatim, but writing out my ideas ahead of time and referencing the script as I record is a large part of why each episode sounds tight and well organized-- “smooth,” as many listeners say.

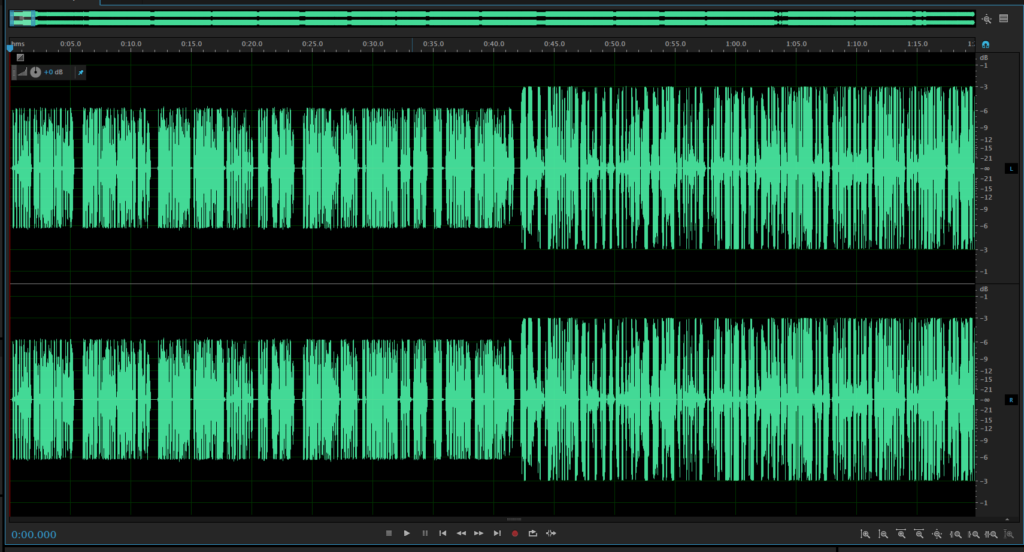

Editing serves as the other reason why episodes sound tight and coherent. Each episode receives a minimum of three rounds of editing. I conduct the first and third rounds, my audio engineer (Darrell Darnell) conducts the second and possibly fourth rounds. We edit each interview in a program called Adobe Audition. Audition works like a word processor for audio files. I record each interview as a .wav file and Audition allows me to read the interview by displaying it’s waveforms. You read through audio files by listening to the interview and watching the waveforms.

The First Edit: I look and listen for long breath sounds, pauses, unnecessary tangents, misstated information, and whether I can improve the flow of an interview by restating a question, shortening an answer, or by moving around questions and answers. When I find a section I want to remove, I use Audition’s delete or cut feature much like we use the delete key in our word processor.

Occasionally, I find misstated information and I try to correct it. For example, one guest said “Rhode Island” when they meant “New Hampshire.” Neither of us heard this mistake during our conversation, but I caught it during the edit. As my guest said “New Hampshire” elsewhere in the interview, I used Audition’s copy and paste feature to replace the misstated “Rhode Island” with “New Hampshire."

I would classify the edits I make in this first round as content edits. I focus on the content of the episode and use the remove, copy, and paste tools to get the “text” of the episode how I want it.

The Second Edit: Darrell goes through the edited files and focuses on cleaning up the audio. He removes most of the ahs and ums, long breath sounds, and long pauses. He also levels the waveforms so the volume of the recording sounds even, adds my intro, outro, and bumper segments (show music), and adds compression to the file. Darrell is the magician behind the fantastic audio quality of each episode.

The Third Edit: At this point the file is equivalent to the page proofs of an article or manuscript. It’s just about ready for publication but it needs a final proof read. I listen through the file to determine whether we need to cut or add anything else from the episode and whether the audio has imperfections we need tweak. If I find a problem in the proof, I send the file back to Darrell and he fixes it.

Editing is the most time intensive part of producing episodes. To save time most podcasters either don’t edit or they hire out this work completely. Outsourcing all of the editing for a podcast about history doesn’t work. Unless the engineer has had historical training, they cannot write and edit historical content the way a historian can.

Conclusion

Historians' ability to research, analyze, interpret, and write makes us well suited to convey our scholarship through digital media. The only special training historians need to work in digital media is time: time to research the different voice(s) of the media they want to work in, time to read a few how-to books or blog posts about how to use software like WordPress or Audition, and time to ask questions of others who work in the same medium.

As we complete the second decade of the 21st century, we need to stop viewing “digital history” projects, like podcasts, as separate or “non-traditional" categories of the historical discipline. This outlook has created a mental hurdle that prevents many historians from trying and embracing new media; media which our traditional work is well suited for and which can extend the reach of our work beyond those who read our books and journal articles.

A Podcast Network for Historians?

What if historians owned and operated a media network?

How much impact could they make with the ability to create wide public awareness about their research?

What if historians owned and operated a media network?

How much impact could they make with the ability to create wide public awareness about their research?

Last week, I attended Podfest, one of the two major conferences about podcasting in the United States. I used the opportunity to share ideas, meet with friends, and help new podcasters launch their shows.

As I shared my ideas, four veteran podcasters told me they had an idea for me too: Think BIGGER.

They suggested that I parlay the success of Ben Franklin's World into a history podcast network.

Truthfully, I had this idea last year, but I became busy and I haven't thought about it for awhile. Now the podcasters' suggestions have me thinking about it again.

In this post, you will discover what podcast networks are, the benefits they offer, and an overview for how to start one.

Podcast Networks

A podcast network is a group or company that produces, promotes, sells ad space on, and manages more than one podcast.

Some networks, like Gimlet Media and Radiotopia, own all of their own shows. Other networks, like Panoply, own some shows and manage the distribution, promotion, and ad sales for other shows they invited to join their network.

Network Benefits

Podcast networks offer many benefits, although not all networks offer all benefits.

1. Consistent content: Finding high-quality content can be difficult. Podcast networks offer listeners and advertisers an easy way to find shows with similar quality and/or topic(s) to the shows they already like.

Many networks offer programs that have a similar genre or topic. Gimlet Media produces a variety of storytelling podcasts. Radiotopia offers both storytelling and editorial shows.

2. Training and Editorial Assistance: Networks offer show hosts training and editorial guidance.

Networks that own all of their shows have producers who help hosts come up with show ideas, strategies for how to implement those ideas, and editorial assistance when it comes time to edit the show together. They also ensure that a consistent group of audio engineers edit and master episodes.

Networks that own some shows, but not all shows, may offer their members all or some of the above services.

3. Promotion: Word-of-mouth recommendations provide podcasts with the best avenue for finding new listeners.

Networks find new listeners for their programs by promoting member shows across their network. This promotion generates lots of word-of-mouth support that can quickly expand listenership for new programs because listeners are more likely to check out podcasts that belong to the same network. Listeners like consistent quality.

4. Bulk and Centralized Ad Sales: Advertisers want to invest in ads that generate awareness and sales. They want to work with companies (or networks) that have a track record of producing high-quality, consistently-released content that their target audience consumes.

Networks offer advertisers stability and opportunities to be heard by members of their target audience across multiple shows.

Why a Historian Operated Network

History is one of the most popular podcast genres. The most popular history podcast (and one of the most popular podcasts) is Dan Carlin's Hardcore History. New episodes of Carlin's podcast receive approximately 3 million downloads within the first month of availability.

The present landscape of history podcasts reflects that journalists and amateur historians, like Carlin, produce most of the podcasts about history. Although several of these podcasts are good, most reflect a lack of professional historical training.

A podcast network operated by historians would offer historians the ability to both professionalize and participate in a popular genre of a steadily growing media. The fact that such a network could tout podcasts produced by professional historians would provide its member shows with instant credibility.

Another advantage for historians: the network could be built into a sizable media outlet historians could always use and control. No more waiting for NPR, The New York Times, or the History Channel to come calling. In fact, a podcast network would increase the visibility of historians and their important work. This in turn would increase the frequency that popular media outlets would contact us.

Brief Overview for How to Start a Podcast Network

The first step for creating a historian-driven podcast network is to settle on an approach.

Will the network produce and own all member podcasts? Will it own some and invite other hosts to participate? Will it offer shows about any historical topic? Or will it offer shows related to a certain era, geographic area, or subfield?

The network would need a name. This name would need a domain name for its online presence, incorporation as a business entity, and trademark protection.

With legalities in place, the network would need to produce or find its first show(s). The selection/production of this show(s) is incredibly important because it will establish the reputation of the network with listeners and help the network gain an audience.

Once the network felt secure in the production of its first show it could create or add member shows. The addition and creation of member shows would likely be dependent upon the first show generating revenue from advertisements and affiliate opportunities.

Will I Start A Historian-Run Podcast Network?

Will I follow the podcasters’ advice and use Ben Franklin’s World to start a historian-driven podcast network?

I don't know.

I have the knowledge and a well-established first show. I also know I could help historians learn how to podcast and produce great, compelling content.

But, starting a network would require me to place my current research and publication plans largely on hold for an unknown period of time. Sure, I could create opportunities to blend my research agenda with that of the network, but it may take several years before I could really go back into the archives and work on a book-length project.

There is also the fact that starting a network would multiply the business/administrative aspects of producing a podcast that I don't always enjoy.

Network creators are both the face of the network and its "janitor." I would be responsible for finding and training new talent, creating or finding new shows, managing network hosts and show edits, show promotion, finding and securing advertising partners, and solving problems that arise.

With that said, I love the idea of building something that would allow historians to expand the reach and impact of their important research. And I think I could find a partner or two to assist with the administrative work.

Now is also the perfect time to start a network.

Historians are embracing the history communications movement and podcast networks and digital content providers are beginning to bring order to the "Wild West" atmosphere of digital media. Starting a network now will be easier than it will be two years from now. And starting now would give historians the opportunity to help shape the order content providers and networks are applying to the digital media landscape.

Over the last six months or so, I have felt like I am standing at a crossroads with my work, but I couldn’t articulate why. The idea of starting a network has forced me to figure out why I have this feeling. It’s because I need to make a choice about the type of scholarship I want to produce over the long term.

Do I want to be a historian who dabbles in digital media and researches and writes books and articles that contribute to the historiography?

Or do I want to be a historian who uses their training to shape the way historians utilize new media to present their scholarship to the world?

I have been podcasting long enough, and I see the landscape well enough, to know that I have to make this choice and I must make it soon. If I wait too long, I will miss this opportune moment.

Edupreneur or Institutional Historian? Questions Raised by SHEAR & Podcast Movement

This past weekend, I attended Podcast Movement, the world’s largest podcast conference.

In this post, I reveal the ideas Podcast Movement 2015 gave me and helped me to articulate, including the idea of whether I want to be an edupreneur or an institutional historian.

This past weekend, I attended Podcast Movement, the world’s largest podcast conference.

In this post, I reveal the ideas Podcast Movement 2015 gave me and helped me to articulate, including the idea of whether I want to be an edupreneur or an institutional historian.

Culture Shock

Podcast Movement marked my first non-academic conference and it left me with a feeling of culture shock for two reasons: First, the conference took place in Fort Worth, Texas.

Second, I attended the conference as an historian in a world that appears dominated by marketers.

A New England Yankee in Fort Worth, Texas

My trip to Podcast Movement marked my first visit to the Dallas/Fort Worth area. I have visited Houston twice and find it to be a cosmopolitan city that sprawls like no other city I have ever visited (even Los Angeles). Although I have enjoyed my visits to Houston, I will admit that I left disappointed that it didn’t feel like the Texas I had imagined.

I am disappointed no longer.

Not long after I deplaned in Fort Worth, I asked for directions to the shared van stand. The man who assisted me called me “darlin’” and pointed the way. I had expected a slightly southern accent, but the term caught me off guard. I couldn’t help but think that my helpful guide was being a bit fresh.

It turns out, he wasn’t being brazen. When I reached the shared van stand the male attendant also used “darlin’” to address me. In Texas, “darlin” is used in place of “ma’am.”

Other cultural experiences included country music (not the pop kind), cowboy boots (Texans really wear them), choices regarding the pork and beef you put in your Tex-Mex tacos (choices?), and a few other linguistic variations.

My visit to Fort Worth reminded me why I love, and am so fascinated by, the United States. The U.S. stands as a huge country, with many regional identities, and yet every citizen who lives within its borders proclaims to be “an American.” We portray ourselves as one people and yet Americans in Fort Worth, Texas are different from Americans in Boston, Massachusetts.

An Historian Attends a Non-Academic Conference

What happens when you attend a non-academic conference? You get a hefty conference badge and a swag bag!

Inside my swag bag I found a glossy, color program, ads for corporate sponsors, a book, sunglasses, and a portable power stick to charge my smartphone or tablet.

Aside from the swag bag, I experienced business card overload.

A friend told me that I should bring at least 100 business cards to the conference and develop a system for dealing with the business cards I received. I laughed at these suggestions.

Earlier this month I attended SHEAR. I handed out more business cards at SHEAR than I have ever handed out at one conference; I probably gave out between 15-20. At SHEAR and other academic conferences I follow the tried and true etiquette of giving a card only when asked or when I want someone to remember me after a conversation.

At Podcast Movement, attendees handed out business cards to everyone they saw, regardless of whether they engaged you in conversation.

I must have given out between 75 and 80 business cards and between 100-200 Ben Franklin’s World bookmarks. I think I came home with more than 100 business cards.

Finally, I have never been to a conference where so many of speakers presented without being aware of the composition of their audience.

Podcast Movement attracted an audience of hobbyists, business owners, marketers, and public radio professionals. I enjoyed many conference sessions and panel discussions, but the public radio professionals spoke to everyone as if their audience worked in public radio and had NPR’s budget. As small as NPR’s budget may be, it is much bigger than that of an indy podcaster.

Additionally, many of the presenters at “How-To Monetize Your Podcast” sessions spent more time selling themselves than they did conveying useful information about how a podcaster could court advertisers or develop salable products. They were marketers, not educators.

When you attend a history conference, nearly every presenter knows their audience. I found the change of pace at this quasi-business conference a bit jarring at times.

Standing at a Crossroads

As different as Podcast Movement was from the academic conferences I normally attend, I had a really good time. I met many amazing podcasters and made several new friends. I heard fantastic talks given by Roman Mars (I met him too!), Marc Maron, and Sarah Koenig. I also came home with several ideas about how I can tweak Ben Franklin’s World and grow its audience.

I plan to start with developing an app and by seeking crowdfunding.

Attending both SHEAR and Podcast Movement also helped me articulate that I feel like I am standing at a crossroads with Ben Franklin’s World.

Attending both SHEAR and Podcast Movement also helped me articulate that I feel like I am standing at a crossroads with Ben Franklin’s World.

The podcast started as an experiment. Now that it has and continues to succeed, I need to decide whether I am an “edupreneur” starting a history-based business or whether I am a podcaster looking for an institutional job.

If I am honest with myself, I want to be the latter.

I am an historian and educator. I know little about starting a business and the thought of "monetizing" history makes me uneasy.

At SHEAR some of my colleagues seemed surprised I wasn’t on the job market. They told me I have an impressive work portfolio. I appreciate their recognition, but no institutions place job ads for the type of work I do so I have stopped looking.

Creating public digital history projects is important work, it is the type of work that will return history to the forefront of the public mind, which will in turn help us get funding and increase our enrollment rates.

But public digital history projects do not contribute to our culture’s corporate model of university education. Nor is it the type of work that earns tenure or garners an alternative academic position. I am a digital historian, but I don’t work on databases that lead to a better understanding of historic sources.

There is also the not-so-insignificant price tag that comes with creating and operating a public digital history project. Technology allows us to convey history in incredible and meaningful ways to large public audiences. But technology isn’t always free.

There is also the not-so-insignificant price tag that comes with creating and operating a public digital history project. Technology allows us to convey history in incredible and meaningful ways to large public audiences. But technology isn’t always free.

Ben Franklin’s World costs approximately $90 per episode to produce (sometimes more) and this cost does not include my time.

If I fulfill my goal of completely outsourcing my audio editing, each episode will cost $165, again not including my time. This cost is far less than NPR spends on each of its podcast and radio episodes, but it still means that a project such as mine requires a minimum operating budget of $360-$450 per month to keep it going.

Ideally, I would have a budget of $660-$825 per month so I can create more time for my scholarship.

In a perfect world, my monthly budget would be closer to $1,000 per month so I could hire graduate students to find and attach primary source documents, and suggestions for how educators can use them in their classrooms, to each episode.

I am not sure an institutional digital history job is in my future.

Conclusion

I suppose in the end I will be an edupreneur who holds hope that some day there will be institutional jobs for historians like me. Then we can help institutions build new projects and train others who want to engage in public digital history.

Until that day comes, I will persist in my work. I keep going because I believe that the historical profession has to take history to the public. We need to help our fellow citizens remember why the past and what we do is important. I believe that technology and new media can help us bring history back into the forefront of the public mind.

Until that day comes, I will persist in my work. I keep going because I believe that the historical profession has to take history to the public. We need to help our fellow citizens remember why the past and what we do is important. I believe that technology and new media can help us bring history back into the forefront of the public mind.

I am not sure how long the podcast will continue, but I do know that I want to build a career that includes both traditional archival research and writing and experimentation with public digital history projects. I am not alone in this desire. However, ours is a tricky road.

When we bootstrap and succeed in our work the beancounters at institutions will at some point take note. I think they will appreciate our work, but they will question why they should hire us. We are, after all, doing this important and beneficial work for free. This thought has me staring down the road of edupreneur.