Have you ever visited a place and the history of that place haunted you?

Last week I had the opportunity to visit Munich in the German state of Bavaria. I enjoyed my trip, but I did not sleep well during my visit.

Munich has a long history, one steeped in arts, culture, and innovation. Today, the people of Munich convey and celebrate their rich heritage in their museums, gardens, theaters, and beer halls.

Munich has a long history, one steeped in arts, culture, and innovation. Today, the people of Munich convey and celebrate their rich heritage in their museums, gardens, theaters, and beer halls.

However, one aspect of Munich's somewhat recent history overshadows the rest of its past and it is something that cannot be celebrated, but must be remembered: Munich is the birthplace of Nazism and the concentration camp system.

In this post you will discover Munich and Bavaria’s connection with Nazism and the concentration camp system and how this region of Germany works to keep the memory of its involvement in the Holocaust alive so that Germans will not repeat the past.

Author’s Note

This post has two parts: An overview of the rise of Nazism and the concentration camp system and my efforts to make sense of what I saw, learned, and how I felt (and feel) about it. As a result this is a rather long post, but I believe it needed to be posted in its entirety.

Part 1: Overview of the Rise of Nazism

The End of World War I

At 11:00am on November 11, 1918, World War I ended.

Due to a lack of funds, materiel, and the disintegration of the Central Powers, Germany surrendered.

The surrender shocked Germans throughout Germany. For years the Kaiser and military had told them that Germany was winning the war. The fact that Germans were fighting armies in places such as France and Belgium, but not in Germany added to their shock.

The surrender shocked Germans throughout Germany. For years the Kaiser and military had told them that Germany was winning the war. The fact that Germans were fighting armies in places such as France and Belgium, but not in Germany added to their shock.

As part of the Treaty of Versailles (1919), Germany had to reduce its military from 4 million to 100,000 men. The unemployment of 3.9 million men combined with the stiff reparation payments demanded by the treaty to cripple the German economy.

This environment of fear, anger, and frustration gave birth to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers’ Party) or Nazi Party.

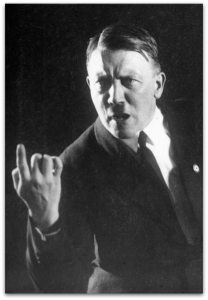

The Rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party

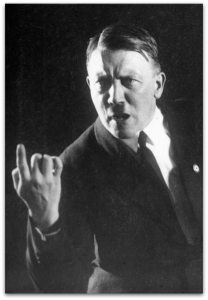

Before the military downsized Corporal Adolf Hitler, it tasked him with monitoring the activities of the German Workers’ Party, which Anton Drexler (an ardent German nationalist) had organized in Munich in 1918.

The nationalist message of Drexler’s party attracted Hitler and he began working for it after the army discharged him. At first, Hitler served the party by drumming up support. His chief talent laid in gaining new members through his fiery speeches.

Hitler had a talent for oratory. He knew how to engage and energize an audience. He began by capturing his listeners' attentions with some wry humor and light banter. This technique allowed Hitler to read his audience. Once he judged his listeners he told them what they wanted to hear. Hitler became more animated as his speech continued. By the time he reached the portion of the speech where he talked about the Workers’ Party ideology both he and his audience were captivated and animated about what he had to say.

Hitler had a talent for oratory. He knew how to engage and energize an audience. He began by capturing his listeners' attentions with some wry humor and light banter. This technique allowed Hitler to read his audience. Once he judged his listeners he told them what they wanted to hear. Hitler became more animated as his speech continued. By the time he reached the portion of the speech where he talked about the Workers’ Party ideology both he and his audience were captivated and animated about what he had to say.

A turning point for the small German Workers' Party came when Hitler convinced Drexler to rent the large banquet hall in Munich’s Hofbräuhaus, one of the largest beer halls in the world. Hitler’s speech proved a success and from there he began talking at many of Munich’s large beer halls.

Hitler proved so successful at gaining new members through his oratory that on July 28, 1921, party leaders elected him chairman and gave him sole leadership. Thus, Hitler became the Führer of the German Workers’ Party, which had since became the National Socialist Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei) or Nazi Party for short.

The Nazi Party became successful because of its strong support in Munich and because Ernst Röhm supplied it with military-grade weapons. During the late 1910s and 1920s, German political culture necessitated the need for party members to protect their orators; most political discussion took place in beer halls where attendees threw beer tankards and brawled. Hitler and the Nazis created a security force called the Sturmabteilug (Storm Detachment or Assault Division) or SA for short. The SA served as the predecessor of the SS.

The Nazi Party became successful because of its strong support in Munich and because Ernst Röhm supplied it with military-grade weapons. During the late 1910s and 1920s, German political culture necessitated the need for party members to protect their orators; most political discussion took place in beer halls where attendees threw beer tankards and brawled. Hitler and the Nazis created a security force called the Sturmabteilug (Storm Detachment or Assault Division) or SA for short. The SA served as the predecessor of the SS.

In 1923, Germany suffered from hyperinflation. Frustrated with the government of the Weimar Republic, many Bavarian statesmen considered secession. As an ardent nationalist, the secession of Bavaria did not fit in with Hitler's plans for the republic.

On November 8, 1923, three prominent Bavarian state officials planned to speak about Bavarian independence in front of 3,000 people at the Bürgerbräuskeller in Munich. Believing that he had the support of the people and the force of his SA troops (and their weapons), Hitler attempted to seize power.

Hitler’s “Beer Hall Putsch” ended with the death of sixteen Nazi SA members, four Munich police officers, and Hitler's arrest and imprisonment for treason. The judge sentenced Hitler and his follower Rudolf Hess to five years in prison; Hitler served nine months before he was released for good behavior.

The Nazi Party almost died out but surged in popularity in both Munich and in other German states after the stock market crash in 1929.

In 1932, the Nazi’s secured enough votes that Hitler was allowed to form a coalition government. On January 30, 1933 he became Chancellor of Germany.

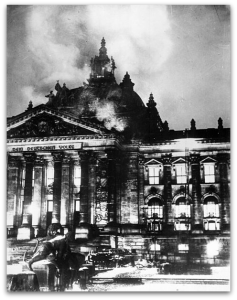

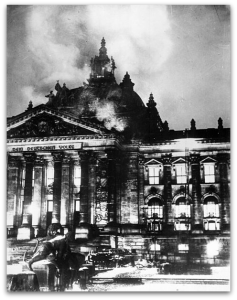

The Reichstag Fire & the Creation of Dachau

On February 27, 1933, a Dutch communist named Marinus van der Lubbe set fire to the Reichstag or German Parliament building. Hitler used this act of terrorism as an excuse to ask Parliament to place Germany under a state of marital law while he sought out van der Lubbe’s accomplices (van der Lubbe declared that he acted alone). Parliament agreed and issued the Reichstag Fire Decree.

On February 27, 1933, a Dutch communist named Marinus van der Lubbe set fire to the Reichstag or German Parliament building. Hitler used this act of terrorism as an excuse to ask Parliament to place Germany under a state of marital law while he sought out van der Lubbe’s accomplices (van der Lubbe declared that he acted alone). Parliament agreed and issued the Reichstag Fire Decree.

Hitler used the Reichstag Fire Decree and the emergency powers it gave him to quash those who opposed the Nazi Party. SA officers rounded up Hitler's political rivals and opponents (primarily communitsts, socialists, and Jews) and placed them in jail.

By March 1933, Hitler ran out of places to put his political prisoners as city and state jails overfilled with them. Munich Police President Heinrich Himmler offered Hitler a solution: just outside of Munich the town of Dachau had an abandoned warehouse and ammunition factory. Hitler could use this facility as a place to “concentrate” his political prisoners.

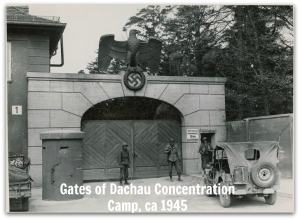

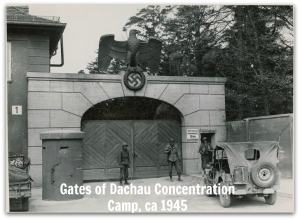

Dachau Concentration Camp

The Dachau Concentration Camp opened on March 22, 1933. It had the capacity to hold approximately 5,000 men.

The Dachau Concentration Camp opened on March 22, 1933. It had the capacity to hold approximately 5,000 men.

Initially, the camp fell under the purview of the Bavarian State Police. However, by April 10, 1933 Hitler's SS unit (which had replaced the SA in March 1933) oversaw the camp.

The SS imposed a systematic regime of physical and mental torture. My tour guide referred to Dachau as the “School of Violence,” the place where the SS trained its soldiers in the arts of torture and murder.

Prisoners at Dachau had no rights because, as they were informed upon their arrival, they were not human: They were pigs and scum.

As a forced-labor prison, the initial prisoners built the facilities of the camp. The first building they renovated/built was the “bunker.” The cells in this building had been converted from a row of double lavatories and outfitted with wooden plank beds. It quickly became a torture chamber.

New prisoners arrived at the “bunker” where the SS dehumanized them. The SS welcomed new prisoners with 25 lashes from a bullwhip. The SS often compelled other prisoners to inflict the lashes either with the offer of a food or alcohol reward or with the threat that they would be dealt a harsher punishment if they refused.

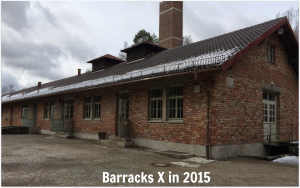

When the prisoners completed construction of the camp it consisted of the jourhouse (entry gate and SS offices), the bunker, thirty-four barracks, a crematorium (complete with gas chamber), a maintenance building, and seven or eight watchtowers. Each barrack was designed to hold about 208 prisoners, but towards the end of the war they housed over 2,000.

When the prisoners completed construction of the camp it consisted of the jourhouse (entry gate and SS offices), the bunker, thirty-four barracks, a crematorium (complete with gas chamber), a maintenance building, and seven or eight watchtowers. Each barrack was designed to hold about 208 prisoners, but towards the end of the war they housed over 2,000.

Dachau was not a secret place, everyone in Germany and many outside of Germany knew of its existence. A “joke” or rhyme of sorts developed that warned Germans to watch what they said or they might end up in Dachau.

Dachau became the model by which all other concentration camps inside and outside of Germany followed in terms of prisoner housing and treatment. Dachau always served as a prison for political prisoners.

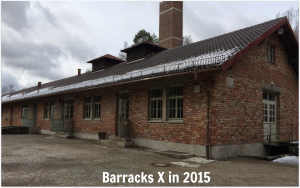

Although Dachau had a gas chamber in its crematorium, or “Barracks X," it was never used (no one knows why). The Nazis sent thousands of Jews to Dachau, but often the camp proved a temporary stop. The Nazis sent most of the Jews who arrived at Dachau to other “death” concentration camps outside of Germany.

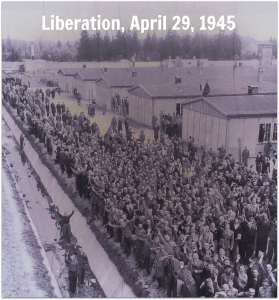

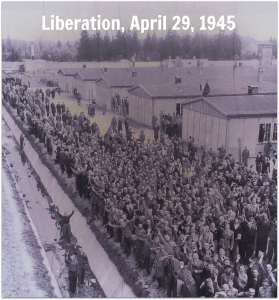

Documents record that nearly 32,000 prisoners died at Dachau, mostly men as it was a men’s camp. American forces liberated the camp on April 29, 1945. Newspapers reported that the Americans liberated near 30,000 Jewish and political prisoners.

Documents record that nearly 32,000 prisoners died at Dachau, mostly men as it was a men’s camp. American forces liberated the camp on April 29, 1945. Newspapers reported that the Americans liberated near 30,000 Jewish and political prisoners.

The sight of the camp horrified the American soldiers who liberated it-- men starved to skin and bones, many ill with Typhus, and thousands of bodies strewn everywhere as the SS had run out of coal for the crematorium.

Then there were the bodies in the so-called “death train.”

Three days before the SS surrendered Dachau to the Americans, they forced near 10,000 prisoners to leave the camp for other camps. The SS forced near 7,000 prisoners to march on foot; 1,000 of them died along the way. The SS crammed 3,000 prisoners into train cars, which did not make it far from the camp.

German Historical Memory

Today, the people of Munich do not hide from their state and city’s involvement with Hitler’s rise to power or from the atrocities committed at Dachau.

Today, the people of Munich do not hide from their state and city’s involvement with Hitler’s rise to power or from the atrocities committed at Dachau.

Officially, the German nation strives to prevent a reoccurrence of the atrocities that happened during the twelve years of Nazi rule by making sure that no German forgets their past. To this end, the German government funds the upkeep of all the remaining concentration camps, which serve as memorial sites (open free of charge) to the victims of the Holocaust.

Germany also requires all school children to visit a concentration camp. This is in addition to reparation payments that the country has made to victims of the Holocaust. (It took many years, but German businesses such as Volkswagen and BMW also offer reparations payments to concentration camp prisoners whose labor they purchased and profited from during the war.)

Moreover, it is illegal to display the Nazi swastika outside of a museum or to offer the “Hitler Salute." If you are caught offering the “Hitler salute” in Germany you will be arrested and fined one month’s pay for your first offense. If caught a second time you will be imprisoned for three years without hope of parole.

State and municipal governments also strive to remember the past. The Munich City Museum has a permanent exhibit on the rise of National Socialism in Munich.

Unofficially, I met several Germans who apologized for their past. For example, the day before we visited Dachau, Tim I took a trip into the Bavarian Alps. At some point our bus passed a site that evoked World War II and our guide mentioned how crazy Hitler was and offered an apology for the past.

The Nazis governed Germany for twelve years, a blip in the grand scheme of German history. And yet, today this blip overshadows the rest of its history. But neither the Germans I met nor the historic sites I visited hid from this past. Instead, they acknowledged the period of 1933-1945 as an awful, horrific time and they work tirelessly to ensure that all Germans keep the memory of the Holocaust present in their minds so they do not repeat the past.

Part 2: Thinking About American Historical Memory

Conclusions

I admit that I did not sleep well while in Munich.

I enjoyed learning about the German past, but the horrors of Nazism and World War II seemed ever present. I could not escape the period. Even when I visited much earlier historic sites many had been damaged or completely rebuilt as a result of Allied bombing during the World War II.

And yet, I was also comforted by the fact that I was mentally uncomfortable.

History can't and shouldn't always be comfortable to think about. It's the difficult and uncomfortable memories of the past that help to keep us from repeating it.

I think we Americans can learn a lot from the Germans' efforts to make amends for their past by keeping its uncomfortable memory alive.

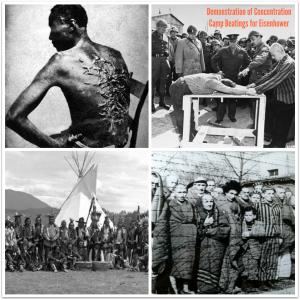

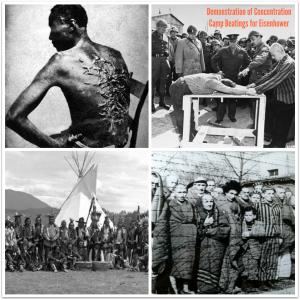

As I toured Dachau, my mind couldn’t help but try to make sense of the atrocities that happened there and throughout the concentration camp system. As our tour guide described the physical and mental torture the SS inflicted upon the inmates my mind brought me back to early America. Much of the torture and abuse he described (and showed us pictures of) reminded me of the American institution of slavery.

American slavery was a system predicated upon the idea that Africans and African Americans were subhuman creatures. Slave owners and overseers forced slaves to work hard, sometimes underfed them, and inflicted an array of physical and mental torture upon them.

In Dachau, the SS believed their prisoners to be subhuman. They forced them to labor hard, beat, or ordered the beating of, prisoners they thought willful, guilty of a transgression, or for some other contrived reason.

In Dachau, the SS believed their prisoners to be subhuman. They forced them to labor hard, beat, or ordered the beating of, prisoners they thought willful, guilty of a transgression, or for some other contrived reason.

The SS employed kapos or prisoners to enforce order in concentration camp barracks just as some slave masters elevated slaves to oversee the work of their fellow slaves. Both slave overseers and kapos received special treatment for their work and received similar punishment if they failed at their job: re-entry into the general population they had helped abuse, which likely meant death.

My mind also drew me to compare the Nazi’s execution and concentration of political opponents and other “undesirable” peoples with the Americans’ treatment of Native Americans. From the colonial period through the nineteenth century, Americans viewed Native Americans as inferior peoples and worked to either eliminate their populations or concentrate them on reservations.

The American system of slavery and treatment of Native Americans are not exact comparisons for the Nazis' concentration camp system or the Holocaust they perpetrated, but there are enough similarities that I found my visit to Dachau and Munich sobering.

My visit to Germany made me feel ashamed. Germans acknowledge and apologize for their ancestors' complicity in World War II and the Holocaust and yet Americans refuse to do the same for their horrific past.

The United States has never offered an official, state apology for slavery and many museums and textbooks still gloss and whitewash over the horrors of slavery and American treatment of Native Americans. This is a difficult past and we need come to terms with it. I do not believe that our nation will ever work out its sectional issues or its problems with race until we acknowledge our difficult past.

Admittedly, unlike the Germans, we Americans have the luxury of avoiding our past. Slavery did not leave behind bombed out buildings that we had to rebuild and then walk by every day, at least not in the North and not in a way that southern Americans associate the damage of the Civil War with slavery. It is easy for us to ignore our uncomfortable history, but it is also weak and cowardly.

Many Americans see acknowledging the mistakes of our ancestors to be a sign of weakness. But, the Germans show us that the act requires strength and courage.

Where do book ideas come from?

As a first and second year graduate student, I was obsessed with this question. I spent an inordinate amount of time wondering how my professors came up with great article, book, and dissertation topics.

Where do book ideas come from?

As a first and second year graduate student, I was obsessed with this question. I spent an inordinate amount of time wondering how my professors came up with great article, book, and dissertation topics. There is a dearth of information about American life and the economy of the new United States between 1783 and the mid-1790s.

There is a dearth of information about American life and the economy of the new United States between 1783 and the mid-1790s.