I have been monitoring a few trends in digital communications.

In this post, I will discuss what I have noticed, where I think it is all going, and why historians should care.

General Observations

Digital communications has entered a “Wild West” period. Digital audio, video, and magazines have been around long enough that people know how to start and produce content for them. Today, the focus is not on content creation, but on how to monetize digital media.

There are four major players driving digital media monetization trends: Traditional media networks, digital media networks, internet entrepreneurs, and consumers.

Consumers want to locate high-quality, digital content that interests them quickly and reliably. Traditional media networks, digital media networks, and internet entrepreneurs aim to service this consumer demand by providing high-quality, easy-to-find, niche content to consumers as part of membership/subscription programs.

The future of digital media is content curation and bundling.[1]

Rise and Proliferation of Podcast Networks

At a casual glance, the world of podcasts might seem like a free-for-all. In fact, consolidation has begun.

At a casual glance, the world of podcasts might seem like a free-for-all. In fact, consolidation has begun.

The number of podcast networks has exploded over the last year.

A few of these networks developed out of traditional media such as the NPR podcast network. The majority have their roots in digital communications such as Panoply (Slate), Rainmaker.FM (Copyblogger), and Earwolf (Midroll). Others had a hybrid birth: Radiotopia and Gimlet began as digital networks, but their founders came from NPR.

Networks allow participants to cross-promote member shows to audience members who already enjoy one or two shows within that network. As a result, shows within a network tend to grow large audiences.

Additionally, networks offer bundled ad buys to advertisers. Ad revenue proceeds do not always divide equally. The network takes significant cut for maintenance and advertising fees and shows with larger audiences receive higher percentages than shows with smaller audiences.

More Players Enter the Digital Audio Game

Competition has been stiff in the realm of digital video.

Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu all offer original video content. YouTube stands as the second largest search engine and internet video producers have started to hyper-specialize in the content they produce to stand out on the platform.

The same has not been the case for audio.

Apple has dominated the podcast market.

As of July 2015, 82 percent of all podcast listeners listened on an iPhone. iTunes and the Apple Podcasts App account for more than 50 percent of all podcast downloads. The closest competitor to iTunes has been Stitcher Radio, which supplies approximately 2.5 percent of all podcast downloads.

As of July 2015, 82 percent of all podcast listeners listened on an iPhone. iTunes and the Apple Podcasts App account for more than 50 percent of all podcast downloads. The closest competitor to iTunes has been Stitcher Radio, which supplies approximately 2.5 percent of all podcast downloads.

However, Apple is about to experience serious competition to its near monopoly as a gateway to digital audio.

During the last 4-6 months, more digital media companies have either entered or have made strides to enter the digital audio market.

In May 2015, Spotify released a beta program to curate podcast content. Since June, the company has hand selected podcasts to include in its service and each month it expands its podcast offerings for its beta user group.

On October 27, 2015, Google announced its reentry into podcasts. Google Play Audio is now accepting submissions for its Google Play Music podcast directory.

On November 2, 2015, Pandora revealed that it will be the “exclusive streaming partner” for season 2 of Serial, the most popular podcast to date.

Amazon stands as the only major player that has not announced a plan to incorporate podcasts into its media offerings.

Membership Has its Privileges

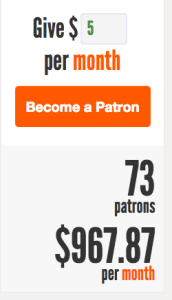

Smaller podcast (audio and video) networks have begun to mimic their large counterparts. Just as Google Play Music, Amazon Prime, Spotify, Pandora, Apple, and Netflix compete to offer unique content to their subscribers, internet entrepreneurs and digital media networks have begun to create membership programs.

Smaller podcast (audio and video) networks have begun to mimic their large counterparts. Just as Google Play Music, Amazon Prime, Spotify, Pandora, Apple, and Netflix compete to offer unique content to their subscribers, internet entrepreneurs and digital media networks have begun to create membership programs.

Panoply (Slate) offers Slate Plus. $50 per year gets you access to all content on the Slate website and extra, members-only premium content.

Gimlet Media is pivoting to the membership model too. Listeners who support the network at $60/year receive a t-shirt and access to behind-the-scenes content.

Radiotopia also offers swag for listeners who subscribe to its monthly donation options. However, listeners who subscribe at the $20/month or $300/year level also get the chance to participate in developing and choosing new talent and shows for the network.

Out in Right Field: Live-Stream Video

This next trend has nothing to do with the consolidation and bundling trends noted above. At least not yet.

This next trend has nothing to do with the consolidation and bundling trends noted above. At least not yet.

Live-stream video is growing in popularity. Millions of people love to watch live video of people doing everything from surfing to delivering a talk on how to save money on your taxes.

People love live-stream video for three reasons: First, it's authentic. Whereas people can stage how they present themselves through static social media posts or edited videos, they can’t hide who they are while streaming live video.

Second, they love live-stream video because it is interactive. Platforms like Periscope, Meerkat, Blab.im, and Google On Air Hangouts allow viewers to interact with the person streaming the video. Viewers can ask questions, offer suggestions, and either harass or support the person streaming in real time.

Third, I suspect people also enjoy live-stream video because of the schadenfreude they feel when they watch someone mess up in front of a live audience.

Why Historians Should Care About Digital Communications Trends

Historians need to be aware of these trends as we consider how best to communicate our work in digital media.

For the moment, I am watching these trends to see which ones have staying power. I suspect that the consolidation and bundling of digital media into networks and subscription platforms is just getting started.

I do not think this movement to curate content as a subscription or membership service will spell the end for independent digital content producers, but when this trend finishes, it will make it significantly harder for independent producers to attract attention and build an audience. After all, the trend is about making it easier for potential readers, listeners, and viewers to find reliable, high-quality content that interests them.

Above, I noted four major players driving this trend. There might be a fifth player shortly: Universities.

At the moment, universities are focused on turning traditional ideas into digital media: They record course lectures and make them available via digital audio or video. This approach is inside-the-box thinking and doesn’t always translate into great digital content.

With that said, there are university departments producing native video, audio, and text content for blogs and podcasts.

The University of Texas-Austin History Department stands out. Check out their blog Not Even Past and the 15 Minute History podcast. UT-Austin history professors and graduate students produce blog and podcast content specifically for each media type. Additionally, although UT-Austin professors and grad students produce all of the content, their media does not reek of self-promotion.

As universities become more involved in digital communications, I can’t help but wonder if digital education communications networks will form, whether they will form along athletic conference lines, and whether they will charge for the content they create and curate.

As universities become more involved in digital communications, I can’t help but wonder if digital education communications networks will form, whether they will form along athletic conference lines, and whether they will charge for the content they create and curate.

Will the bonds that tie the BigTen conference schools together extend to a future scholarly digital communications network?

I don’t know, but it would be powerful if it happens. Especially as the BigTen could advertise its scholarly digital communications network on its traditional television network.

When universities decide to develop digital media content that goes beyond the lecture hall, it will make it more difficult for scholarly digital media produced outside academic institutions to thrive. It may be the outlets such as Ben Franklin’s World, The Junto Blog, and We’re History will continue to prosper because of their longevity. But, new scholarly digital content producers will face a significant challenge as they seek to build an audience for their work.

[1] Bundling involves marketing, packaging, and offering two or more like products or services for one price. A good example of this would be Amazon Prime. The subscription service offers 2-day shipping, video and music streaming, and other services for one, annual membership fee.