This past weekend, I attended Podcast Movement, the world’s largest podcast conference.

In this post, I reveal the ideas Podcast Movement 2015 gave me and helped me to articulate, including the idea of whether I want to be an edupreneur or an institutional historian.

This past weekend, I attended Podcast Movement, the world’s largest podcast conference.

In this post, I reveal the ideas Podcast Movement 2015 gave me and helped me to articulate, including the idea of whether I want to be an edupreneur or an institutional historian.

Culture Shock

Podcast Movement marked my first non-academic conference and it left me with a feeling of culture shock for two reasons: First, the conference took place in Fort Worth, Texas.

Second, I attended the conference as an historian in a world that appears dominated by marketers.

A New England Yankee in Fort Worth, Texas

My trip to Podcast Movement marked my first visit to the Dallas/Fort Worth area. I have visited Houston twice and find it to be a cosmopolitan city that sprawls like no other city I have ever visited (even Los Angeles). Although I have enjoyed my visits to Houston, I will admit that I left disappointed that it didn’t feel like the Texas I had imagined.

I am disappointed no longer.

Not long after I deplaned in Fort Worth, I asked for directions to the shared van stand. The man who assisted me called me “darlin’” and pointed the way. I had expected a slightly southern accent, but the term caught me off guard. I couldn’t help but think that my helpful guide was being a bit fresh.

It turns out, he wasn’t being brazen. When I reached the shared van stand the male attendant also used “darlin’” to address me. In Texas, “darlin” is used in place of “ma’am.”

Other cultural experiences included country music (not the pop kind), cowboy boots (Texans really wear them), choices regarding the pork and beef you put in your Tex-Mex tacos (choices?), and a few other linguistic variations.

My visit to Fort Worth reminded me why I love, and am so fascinated by, the United States. The U.S. stands as a huge country, with many regional identities, and yet every citizen who lives within its borders proclaims to be “an American.” We portray ourselves as one people and yet Americans in Fort Worth, Texas are different from Americans in Boston, Massachusetts.

An Historian Attends a Non-Academic Conference

What happens when you attend a non-academic conference? You get a hefty conference badge and a swag bag!

Inside my swag bag I found a glossy, color program, ads for corporate sponsors, a book, sunglasses, and a portable power stick to charge my smartphone or tablet.

Aside from the swag bag, I experienced business card overload.

A friend told me that I should bring at least 100 business cards to the conference and develop a system for dealing with the business cards I received. I laughed at these suggestions.

Earlier this month I attended SHEAR. I handed out more business cards at SHEAR than I have ever handed out at one conference; I probably gave out between 15-20. At SHEAR and other academic conferences I follow the tried and true etiquette of giving a card only when asked or when I want someone to remember me after a conversation.

At Podcast Movement, attendees handed out business cards to everyone they saw, regardless of whether they engaged you in conversation.

I must have given out between 75 and 80 business cards and between 100-200 Ben Franklin’s World bookmarks. I think I came home with more than 100 business cards.

Finally, I have never been to a conference where so many of speakers presented without being aware of the composition of their audience.

Podcast Movement attracted an audience of hobbyists, business owners, marketers, and public radio professionals. I enjoyed many conference sessions and panel discussions, but the public radio professionals spoke to everyone as if their audience worked in public radio and had NPR’s budget. As small as NPR’s budget may be, it is much bigger than that of an indy podcaster.

Additionally, many of the presenters at “How-To Monetize Your Podcast” sessions spent more time selling themselves than they did conveying useful information about how a podcaster could court advertisers or develop salable products. They were marketers, not educators.

When you attend a history conference, nearly every presenter knows their audience. I found the change of pace at this quasi-business conference a bit jarring at times.

Standing at a Crossroads

As different as Podcast Movement was from the academic conferences I normally attend, I had a really good time. I met many amazing podcasters and made several new friends. I heard fantastic talks given by Roman Mars (I met him too!), Marc Maron, and Sarah Koenig. I also came home with several ideas about how I can tweak Ben Franklin’s World and grow its audience.

I plan to start with developing an app and by seeking crowdfunding.

Attending both SHEAR and Podcast Movement also helped me articulate that I feel like I am standing at a crossroads with Ben Franklin’s World.

Attending both SHEAR and Podcast Movement also helped me articulate that I feel like I am standing at a crossroads with Ben Franklin’s World.

The podcast started as an experiment. Now that it has and continues to succeed, I need to decide whether I am an “edupreneur” starting a history-based business or whether I am a podcaster looking for an institutional job.

If I am honest with myself, I want to be the latter.

I am an historian and educator. I know little about starting a business and the thought of "monetizing" history makes me uneasy.

At SHEAR some of my colleagues seemed surprised I wasn’t on the job market. They told me I have an impressive work portfolio. I appreciate their recognition, but no institutions place job ads for the type of work I do so I have stopped looking.

Creating public digital history projects is important work, it is the type of work that will return history to the forefront of the public mind, which will in turn help us get funding and increase our enrollment rates.

But public digital history projects do not contribute to our culture’s corporate model of university education. Nor is it the type of work that earns tenure or garners an alternative academic position. I am a digital historian, but I don’t work on databases that lead to a better understanding of historic sources.

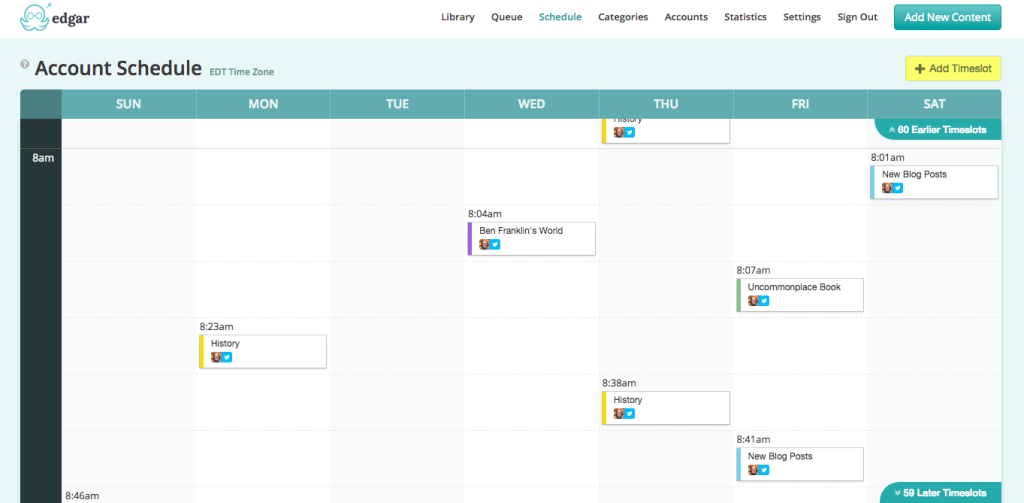

There is also the not-so-insignificant price tag that comes with creating and operating a public digital history project. Technology allows us to convey history in incredible and meaningful ways to large public audiences. But technology isn’t always free.

There is also the not-so-insignificant price tag that comes with creating and operating a public digital history project. Technology allows us to convey history in incredible and meaningful ways to large public audiences. But technology isn’t always free.

Ben Franklin’s World costs approximately $90 per episode to produce (sometimes more) and this cost does not include my time.

If I fulfill my goal of completely outsourcing my audio editing, each episode will cost $165, again not including my time. This cost is far less than NPR spends on each of its podcast and radio episodes, but it still means that a project such as mine requires a minimum operating budget of $360-$450 per month to keep it going.

Ideally, I would have a budget of $660-$825 per month so I can create more time for my scholarship.

In a perfect world, my monthly budget would be closer to $1,000 per month so I could hire graduate students to find and attach primary source documents, and suggestions for how educators can use them in their classrooms, to each episode.

I am not sure an institutional digital history job is in my future.

Conclusion

I suppose in the end I will be an edupreneur who holds hope that some day there will be institutional jobs for historians like me. Then we can help institutions build new projects and train others who want to engage in public digital history.

Until that day comes, I will persist in my work. I keep going because I believe that the historical profession has to take history to the public. We need to help our fellow citizens remember why the past and what we do is important. I believe that technology and new media can help us bring history back into the forefront of the public mind.

Until that day comes, I will persist in my work. I keep going because I believe that the historical profession has to take history to the public. We need to help our fellow citizens remember why the past and what we do is important. I believe that technology and new media can help us bring history back into the forefront of the public mind.

I am not sure how long the podcast will continue, but I do know that I want to build a career that includes both traditional archival research and writing and experimentation with public digital history projects. I am not alone in this desire. However, ours is a tricky road.

When we bootstrap and succeed in our work the beancounters at institutions will at some point take note. I think they will appreciate our work, but they will question why they should hire us. We are, after all, doing this important and beneficial work for free. This thought has me staring down the road of edupreneur.

Eureka! I found it!

I am in New York City this week conducting research at the New York Public Library. I also have a ticket to see Hamilton the Musical.

Eureka! I found it!

I am in New York City this week conducting research at the New York Public Library. I also have a ticket to see Hamilton the Musical.