At NCPH 2016, someone asked the panelists of "Drafting History for the Digital Public" how we acquired the digital skills to work on our various projects. My answer: My historical training drives my digital work.

For the next three days, colleagues asked me about my response and since the conference more questions have found their way into my inbox. Most of the questions inquire about the “specialized” and “technical” training I use to write history for digital audio.

At NCPH 2016, someone asked the panelists of "Drafting History for the Digital Public" how we acquired the digital skills to work on our various projects. My answer: My historical training drives my digital work.

For the next three days, colleagues asked me about my response and since the conference more questions have found their way into my inbox. Most of the questions inquire about the “specialized” and “technical” training I use to write history for digital audio.

Confession: I am a traditional historian using traditional historical skills to work in an accessible digital media.

Ben Franklin's World represents an interview-driven form of narrative history. The end product of each episode may be a digital audio file, but the historian’s traditional tools—research, analysis, interpretation, and writing—give birth to each episode.

In this post, you will take a behind-the-scenes tour of Ben Franklin's World to see how I use my traditional historical training to produce its digital audio content.

Research

Like most history books and journal articles, Ben Franklin's World episodes begin with questions and research.

Listeners determine most episode topics. They e-mail, tweet, Facebook message, and verbally request topics such as the American Revolution, Everyday Life, the Constitutional Convention, and George Rogers Clark. It’s helpful to know what aspects of early American history listeners want to explore, but as we learned in graduate school, what makes history fascinating is asking the right questions of broad topics. It’s up to me to come up with the historical questions each episode will explore.

How do I know what questions to ask and investigate? I research. I look at the historiography to see what arguments and interpretations of the broad topic exist and which historians to contact. After I schedule a guest, I prepare for each interview by reading their work or researching their project/historic site.

Analysis

Analysis plays a role in all stages of episode production. I use the historian’s ability to analyze information when I research episode topics, read guest books and articles, prepare interview questions, interview guests, edit episodes, and when I write episode intros, outros, and show notes.

When I read a book for the show, I read it for information and structure and reference both with the historiography. I facilitate this analysis by taking notes on argument, interesting facts, the historical questions the author asks, their answers to those questions, and how the historian structured their narrative as I read. Upon finishing a book, I review my notes and use my knowledge of the historiography to contextualize the information they contain. This comparison and contextualization allows me to determine what information we should highlight in the interview, how to ask questions that get at the desired information, and how to sequence the questions so that the questions and answers tell a coherent story about the topic of the episode.

It’s the same type of analysis we do when we study for comps, explore the secondary source literature for course reading assignments and lectures, and consider as we determine how to write up our research projects for books and articles.

Interpretation

Ben Franklin’s World seeks to create advocates for history and historical research by generating wide, public awareness about the work of professional historians. The project generates awareness by offering accessible interpretations of the modern historiography of early America.

Each episode contains two types of interpretation: The guest historian’s interpretation of the historical record and my interpretation of their interpretation.

My interpretation comes through in the questions I ask and how I edit each episode. Each question reflects information I want to highlight for listeners. The order in which I ask questions reflects the sequence of how I think listeners should explore or think about historical people, events, and themes.

Historians rely on this type of interpretation every time they offer a lecture, build an exhibit, lead a tour, write a synthesis narrative, or edit a collection of scholarly essays.

Writing

I cannot overstate the role good writing and editing skills have played in the success of Ben Franklin’s World. The reason that most Ben Franklin’s World episodes convey tight, coherent mini-narratives about early American history is my graduate advisor took the time to teach me how to write and edit my work.

Every episode of Ben Franklin’s World relies on a scripted structure and undergoes at least three rounds of editing.

Guest historians offer natural, unscripted responses just as I offer unscripted commentary and follow-up questions. However, I script out the intro and outro for each episode as well as 50 to 80 percent of the questions you hear me ask. This is not to say I read the scripts verbatim, but writing out my ideas ahead of time and referencing the script as I record is a large part of why each episode sounds tight and well organized-- “smooth,” as many listeners say.

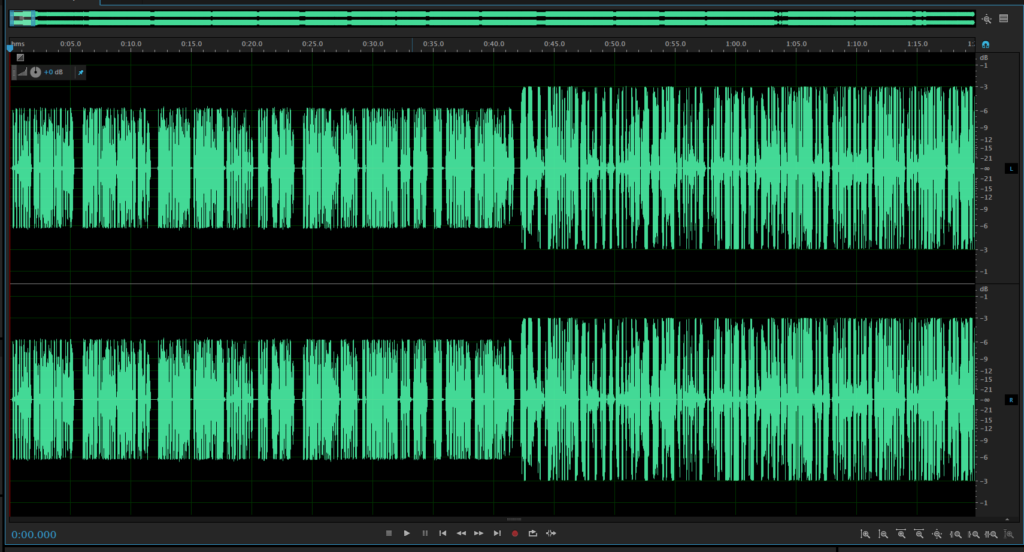

Editing serves as the other reason why episodes sound tight and coherent. Each episode receives a minimum of three rounds of editing. I conduct the first and third rounds, my audio engineer (Darrell Darnell) conducts the second and possibly fourth rounds. We edit each interview in a program called Adobe Audition. Audition works like a word processor for audio files. I record each interview as a .wav file and Audition allows me to read the interview by displaying it’s waveforms. You read through audio files by listening to the interview and watching the waveforms.

The First Edit: I look and listen for long breath sounds, pauses, unnecessary tangents, misstated information, and whether I can improve the flow of an interview by restating a question, shortening an answer, or by moving around questions and answers. When I find a section I want to remove, I use Audition’s delete or cut feature much like we use the delete key in our word processor.

Occasionally, I find misstated information and I try to correct it. For example, one guest said “Rhode Island” when they meant “New Hampshire.” Neither of us heard this mistake during our conversation, but I caught it during the edit. As my guest said “New Hampshire” elsewhere in the interview, I used Audition’s copy and paste feature to replace the misstated “Rhode Island” with “New Hampshire."

I would classify the edits I make in this first round as content edits. I focus on the content of the episode and use the remove, copy, and paste tools to get the “text” of the episode how I want it.

The Second Edit: Darrell goes through the edited files and focuses on cleaning up the audio. He removes most of the ahs and ums, long breath sounds, and long pauses. He also levels the waveforms so the volume of the recording sounds even, adds my intro, outro, and bumper segments (show music), and adds compression to the file. Darrell is the magician behind the fantastic audio quality of each episode.

The Third Edit: At this point the file is equivalent to the page proofs of an article or manuscript. It’s just about ready for publication but it needs a final proof read. I listen through the file to determine whether we need to cut or add anything else from the episode and whether the audio has imperfections we need tweak. If I find a problem in the proof, I send the file back to Darrell and he fixes it.

Editing is the most time intensive part of producing episodes. To save time most podcasters either don’t edit or they hire out this work completely. Outsourcing all of the editing for a podcast about history doesn’t work. Unless the engineer has had historical training, they cannot write and edit historical content the way a historian can.

Conclusion

Historians' ability to research, analyze, interpret, and write makes us well suited to convey our scholarship through digital media. The only special training historians need to work in digital media is time: time to research the different voice(s) of the media they want to work in, time to read a few how-to books or blog posts about how to use software like WordPress or Audition, and time to ask questions of others who work in the same medium.

As we complete the second decade of the 21st century, we need to stop viewing “digital history” projects, like podcasts, as separate or “non-traditional" categories of the historical discipline. This outlook has created a mental hurdle that prevents many historians from trying and embracing new media; media which our traditional work is well suited for and which can extend the reach of our work beyond those who read our books and journal articles.

Do you consider yourself an academic or a public historian?

How do you bridge public and academic history?

Do you consider yourself an academic or a public historian?

How do you bridge public and academic history? What if historians owned and operated a media network?

How much impact could they make with the ability to create wide public awareness about their research?

What if historians owned and operated a media network?

How much impact could they make with the ability to create wide public awareness about their research?

Of late, several professors have inquired whether I offer, or have considered offering, semester-long internships at

Of late, several professors have inquired whether I offer, or have considered offering, semester-long internships at