Reading about the history of vast early America is great. But every so often I find it necessary to go out into the field and see the places I read about. This is, in part, how I came to spend last week in Sint Eustatius, the "Golden Rock" of the 18th-century Atlantic World. This post begins a three-post series about Sint Eustatius, its history, and my visit to the island.

Historic Overview of Sint Eustatius

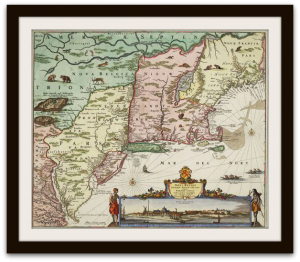

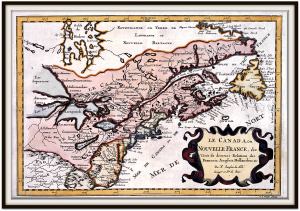

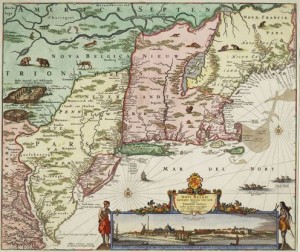

A small, volcanic island in the Lesser Antilles, Sint Eustatius (also known as Statia) stands in between the islands of Saba and Saint Kitts. Archaeological evidence suggests native peoples lived on Statia prior to the 17th century. However, when the French attempted to settle the island in 1629, they no longer lived on Statia.[1]

French settlement of Statia lasted only a few years. The French feared Spanish attacks and they discovered that Statia lacks a natural source of water.

The Dutch found Statia uninhabited in 1636 and settled the island. They recognized the island sat at the crossroads of the trade winds and that it had a large, natural harbor with an easy anchorage that could accommodate up to two hundred ships. To overcome the island's lack of natural water, the Dutch built cisterns.

Under the Dutch, Statia grew in two parts: Lower Town along the shoreline and Upper Town atop the steep cliff where people built their houses, churches, and government offices.

The Dutch built Fort Oranje at the edge of Upper Town's steep cliff and designed it to protect both Upper and Lower Town. By 1701, it had four bastions. Despite its size and strategic location, Fort Oranje never proved capable of staging an adequate defense of the island because the Dutch West India Company never garrisoned enough soldiers on Statia to man it. As a result, the island changed hands between the French, English, and Dutch approximately twenty-two times, often with the exchange of only a couple of shots, between the 17th and 18th centuries.

When the Dutch settled Sint Eustatius, they planned to grow tobacco, cotton, and indigo. By the 18th-century they established sugar plantations. However, these cash-crop plantations proved to be secondary to the main source of Statia's wealth, the slave trade.

Statia's position at the crossroads of the African and American trades brought ships from all over the Atlantic into her large harbor. Duty-free trade supplemented the slave trade especially during times of European warfare. The Dutch often declared neutrality, especially during periods of warfare between the English and French. Dutch neutrality allowed all traders to freely trade in Statia.

Traders could find just about every type of good in Statia. This fact combined with Dutch neutrality caused Americans to sail to Statia in search of gunpowder, ammunition, and other war materiel during the War for American Independence. Historians estimate that as much as 50 percent of the patriots' war supplies came through Statia.

The American Revolution coincided with the peak of Statia's economic power; the days when those around the Atlantic World referred to her as the "Golden Rock." Two notable events occurred on Statia during the Revolution.

First, on November 16, 1776, the American naval vessel Andrew Doria sailed into Statia flying the new flag of the United States. As per custom, she entered the port by firing a peaceful, welcome salute. The Dutch soldiers in Fort Oranje were to supposed to fire a return salute, but they hesitated. They did not recognize the Andrew Doria's flag. The officer on duty inquired with Governor Johannes de Graaff about what action the men in the fort should take. As the welcome salute signified peaceful entry, de Graaff ordered his men to return the salute. The American press spun this customary salute by the Dutch as the first international recognition of the United States, the "first salute."

Second, in 1781, British Admiral George Rodney sailed to Sint Eustatius with orders to subdue the island so the Americans couldn't supply their war effort through it. Rodney sacked the island in February. His orders after subduing the island were to head to the Chesapeake to prevent the French navy from meeting up with George Washington's American army. Rodney defied his orders. He remained in Statia to plunder the island in an effort to satisfy personal debts and enrich himself. As a result, the French met up with the American army at Yorktown in October 1781.

Although the American War for Independence had contributed to Statia's wealth, the independence of the United States also contributed to Statia's decline. After gaining independence, the United States sought to trade in different ports and Statia never recovered from Rodney's plundering. Today, the island, with its population of approximately 3,000 people, is an official municipality of the Netherlands.

[1] No hard evidence exists for why the native inhabitants of Statia left the island. An exhibit in the Sint Eustatius History Museum offered two possibilities: first, native inhabitants left the island in fear the Spanish would raid their island and enslave them. Second, the Spanish raided the island and enslaved its native peoples sometime during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.