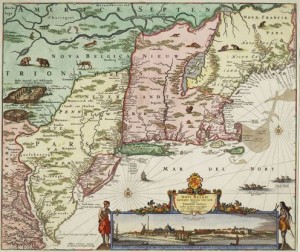

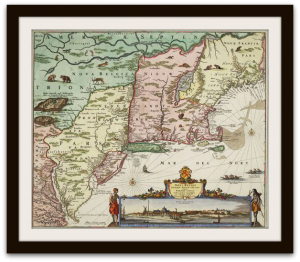

What did the world of the seventeenth-century Hudson Valley look like?

At the 35th Annual Conference on New York State History, historians Leslie Choquette, Jaap Jacobs, Paul Otto, and L.H. Roper grappled with what the region looked like from Native American, Dutch, English, and French perspectives.

What did the world of the seventeenth-century Hudson Valley look like?

At the 35th Annual Conference on New York State History, historians Leslie Choquette, Jaap Jacobs, Paul Otto, and L.H. Roper grappled with what the region looked like from Native American, Dutch, English, and French perspectives.

In this post you will discover what these scholars had to say about life in the Hudson Valley during the seventeenth century.

Rise of English vs. Dutch Competition

Jaap Jacobs discussed how the decentralized nature of the Dutch West India Company and the Dutch East India Company worked well: Decentralization allowed investors to send Dutch ships into the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans to take advantage of new trade opportunities in an organized way.

Jacobs admitted that the Dutch benefitted from the English Civil War (1642-1651) because the English turned their attention inward while the Dutch turned their attention outward. Likewise the Spanish and Portuguese devoted their attentions to their colonies and the closing years of the Eighty Years War. By the 1640s, the Spanish no longer had the means to defend its colonies. With its main competitors distracted, the Dutch expanded their trade networks around the globe.

The Dutch began to face serious competition for global trade during the 1650s. Between 1652 and 1674, the Dutch and English engaged in three wars known as the Anglo-Dutch Wars. Jacobs succinctly expressed the outcomes of these wars:

• 1st Anglo-Dutch War (1652-1654): Marginal victory for the Dutch. • 2nd Anglo-Dutch War (1665-1667): Victory for the Dutch although the Dutch lost New Netherland. • 3rd Anglo-Dutch War (1672-1674): Narrow escape for the Dutch that effectively ended their activities in the Atlantic World.

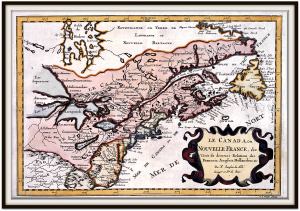

The French

Leslie Choquette outlined the differences between New France, New England, and New Netherland.

The French commenced their North American forays in 1534, when Jacques Cartier explored the St. Lawrence River. Between 1598 and 1608, the French attempted to found trading settlements in New France, all proved unsuccessful. In 1608, Samuel de Champlain founded the city of Quebec with twenty-eight men.

Choquette argued that New France had two characteristics that distinguished it from New England and New Netherland.

Choquette argued that New France had two characteristics that distinguished it from New England and New Netherland.

1. The people of New France formed an alliance with indigenous peoples.

New France suffered from hostility and warfare, but the New French fought distant Native Americans, not those who lived nearby.

2. New France suffered from a very low rate of European immigration, which hampered its development as a colony.

Choquette discussed the need for scholars to move away from nationalistic histories of New France.

English nationalistic histories suggest that New France experienced low immigration because the French were incompetent. They also posit that the French had great relations with the “savages” because they were “savages.”

French nationalistic histories assert that the people of New France coexisted well with their Native American neighbors because the French were a tolerant people. They address low immigration rates to New France by suggesting that no Frenchman wanted to leave “Belle France” and that England experienced high rates of migration to its North American colonies because what Englishman would not want to leave England?

Choquette stated that French-centered histories discount the fact that the French could be just as ruthless as the English and Dutch when it came to dealing with Native American peoples who were not their allies. Both the English- and the French-centered histories also discount the fact that de Champlain had to enter an alliance with Native Americans on Native American terms. He entered the alliance not because the French were tolerant, but because Native American nations controlled the territory outside European colonial settlements.

Native Americans

Paul Otto wants historians to understand that economic, religious, and social norms structured the seventeenth-century encounter between Native American and European peoples in the Hudson Valley.

Otto believes that if historians can understand Native American economic, religious, and social structures then they will have a better sense of what took place in the colonial Hudson Valley; European interactions with Native Americans and Native American participation in those interactions made the formation of societies in the Hudson Valley possible.

Otto asserts that historians must understand two things if they are to understand how colonial society developed around the Hudson Valley:

The Iroquois occupied lands inland from European settlements. The distance between the Haudenosaunee peoples and Europeans gave the Iroquois time to adapt to European settlement before European diseases ravaged their populations.

Historians must also develop a understanding of Haudenosaunee society. Prior to European colonization, the Iroquois had brought their five different linguistic and cultural groups together into one metaphorical longhouse. In this communal longhouse, the Haudenosaunee peoples developed rituals for how to negotiate and deal with their differences. One ritual revolved around wampum and the exchange of wampum to settle disputes and seal agreements.

2. Where did wampum come from?

The Iroquois peoples did not make wampum. They traded for the beads which Munsee peoples along the coast of Long Island and southern New England made from the whelk and quahog shells they found along their beaches.

Long before the arrival of Europeans, the Munsee and Iroquois interacted and exchanged wampum. This trade demonstrates that North America was not a land where people lived in isolation from one another, but a land made up of diverse peoples with sophisticated trade and diplomatic networks.

Otto believes that once historians understand how Native American societies functioned before the arrival of Europeans, they will better understand why European settlements developed as they did because many formed in response to their interactions and relations with the Native American societies around them.

*Picture of wampum belt courtesy of the Iroquois Museum

Audience Q & A Highlights

Audience Q & A Highlights

Both the French and Dutch were seventeenth-century peoples who held similar Christian world views, but why did the Dutch seek to avoid interaction with Native Americans while the French sought close interaction?

Leslie Choquette attributed the close interactions the French had with neighboring Native American peoples to the fact that the French had “lucked out” when they settled in the St. Lawrence Valley. The French settled in an area devoid of Native American farming communities. Sometime between the 1540s and 1600, Native American warfare pushed the Iroquois peoples out of the St. Lawrence Valley. The Iroquois practiced sedentary farming.

The people who inhabited the St. Lawrence Valley when the French arrived lived nomadic and semi-sedentary lives. This meant the French faced little-to-no competition for land. Without competition for land resources, the French had an easier time establishing good relations with the peoples who lived near their settlements.

Choquette also described a major difference between French conceptions of land ownership and Dutch and English understandings of property ownership. The people of seventeenth-century France thought about land in feudal terms. The king owned all the land, but it was possible to farm the king’s land. This feudal conception of property ownership accommodated the idea that both the French and Native American peoples could “own” the same land at the same time.

Paul Otto added that the Dutch and English sent colonists to settle in areas populated by Native American peoples. The Dutch and English sought to farm land that Native Americans also farmed. Competition for the land increased proportionately with the expansion of Dutch and English settlement. He hypothesized that if Dutch and English settlement had occurred on a smaller scale as it had in New France then there would have been less conflict because there would have been less competition for the land.

[simpleazon-image align="left" asin="1438450974" locale="us" height="400" src="http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51YD8J62BsL.jpg" width="232"]Want to Know More?

The panelists collaborated to write [simpleazon-link asin="1438450974" locale="us"]The Worlds of the Seventeenth-Century Hudson Valley[/simpleazon-link]