Welcome to Getting Access, a series devoted to helping you obtain the digital records you need.

Do you study the history of colonial America or New York State?

Welcome to Getting Access, a series devoted to helping you obtain the digital records you need.

Do you study the history of colonial America or New York State?

Do you have an interest in learning about Dutch contributions to American history?

If so, did you know that you can gain access to back issues of de Halve Maen for $10/year? Or that the New Netherland Institute provides free, online access to numerous research materials?

In this post you will learn about digital options for primary- and secondary-source records that pertain to Dutch-American history.

de Halve Maen

Since 1922, The Holland Society of New York has printed a quarterly journal called de Halve Maen.

The publication draws readers' attentions to new research concerning the Dutch settlement of North America and Dutch contributions to American history.

Essays range in topics from agriculture to material culture. They also include articles about Dutch genealogy.

Cost of Access: $10/year for Individuals/$45/year for Institutions

What’s Included with Access?

Your membership includes access to all issues printed between 1923 and 2002.

You will have the ability to keyword search back issues.

You will also have access to: • The Holland Society’s membership records • Digital copies of Van Laer’s New York Historical Manuscripts (Volumes 1-4) • Stokes Iconography of Manhattan Island (Volumes 2-4) • "Liber A" of the Collegiate Church Archives, a folio-manuscript book written by Domine Henricus Selijns, minister of the Reformed Dutch Church in New York (1682-1701).

The records contained in "Liber A" provide a documentary history of the Dutch Reformed Church of New York City during Selijns’ ministry. The volume offered by the Holland Society offers the text in both Dutch and English.

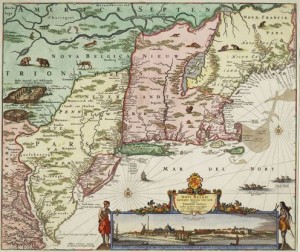

New Netherland Institute Online Publications

The New Netherland Institute offers digitized translations and transcriptions of primary-source documents that relate to the history of New Netherland.

The records come from the collections of the New York State Library and New York State Archives. The Institute has also posted documents owned by the New York Public Library and the Scheepvaart Museum in Amsterdam.

Cost of Access: Free

Which Records Are Online?

- Register of the Provincial Secretary, 1638-1660

- Minutes of the Council of New Netherland, 1652-1654

- Correspondence of Petrus Stuyvesant, Director-General of New Netherland, 1647-1658

- Curaçao Papers, 1640-1665

- Correspondence of Jeremias van Rensselaer

- Correspondence of Maria van Rensselaer

- Court Minutes of Rensselaerswijck

- Memorandum Book of Antony de Hooges

- New Netherland Papers of Hans Bontemantel

- Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts

- Petrus Stuyvesant’s 1665 Certification of Land Grants to Manumitted Slaves

- Guide to 17th-century Dutch Coins, Weights, and Measures

Conclusion

The de Halve Maen and New Netherland Institute databases stand as invaluable resources for any historian or genealogist who wishes to research Dutch-American history.

You will find that the records of the New Netherland Institute focus on the history of New Netherland while those of the Holland Society cover New Netherland and its legacy.

Finally, you should know that New York History has finally added its back issues to J-Stor.

What Do You Think?

What Do You Think?

What is your favorite web-based archive or database? What information does it contain?