What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for Ben Franklin's World.

What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for Ben Franklin's World.

I read these books with the same care and thought I give to scholarly work. I also read them with an eye toward trying to figure out why they are "popular."

Why do history lovers choose these books over scholarly ones, which often contain better evidence, information, and analysis?

In this post, I offer observations about the popularity of popular history books.

Popular History Books Feature People

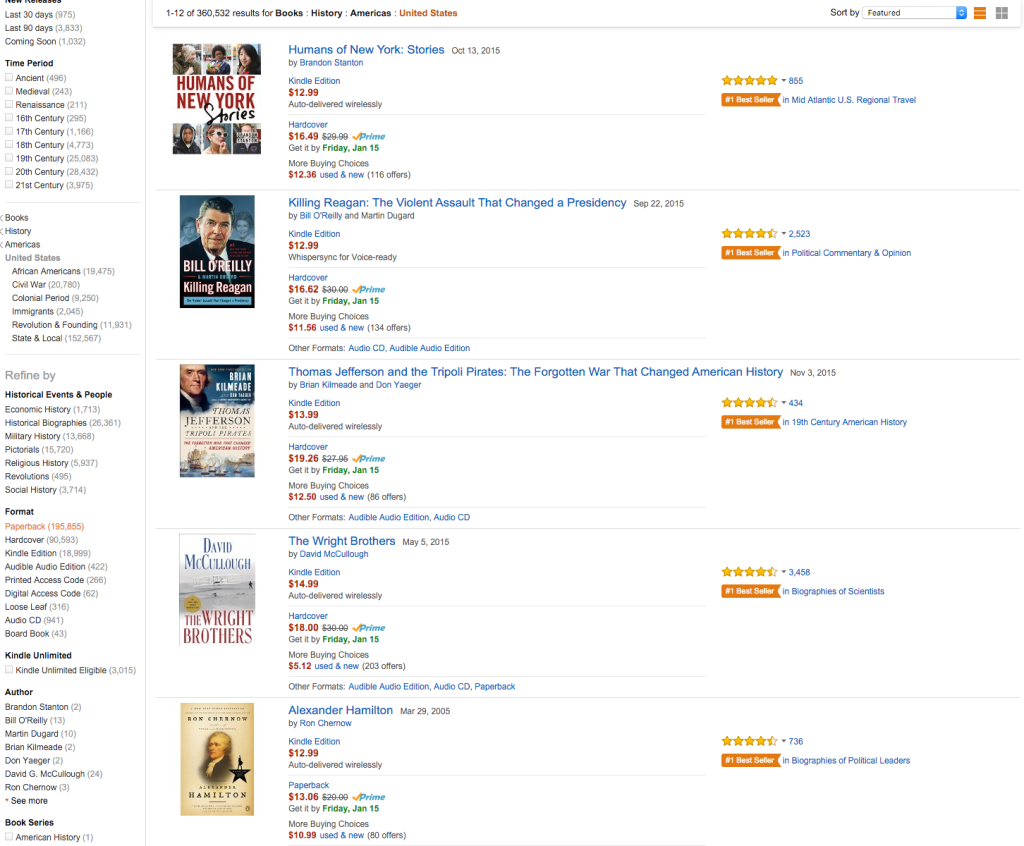

Many historians argue that popular history books are popular because they tackle a founding father or famous person.

A casual glance at the bookshelves or best-seller tables at Barnes and Noble supports this idea.

With that said, I am not convinced that famous people make popular history books popular.

Listeners of Ben Franklin's World love learning about the founders and famous people, but do you know what they love learning about even more?

The lives of everyday people.

Each week, I receive e-mails with requests that I present more episodes about how non-famous, non-elite men and women lived.

You know who tackles this topic best and writes about it the most?

Academic historians.

If readers want to read about everyday men and women, why are popular history books popular?

They are popular because they feature people readers can follow and live through vicariously. I suspect that many history lovers settle for books about George Washington and Thomas Jefferson because they can't find books about people like Martha Ballard or George Robert Twelves Hewes.

The feedback my listeners provide strongly suggests that they would love to read books about men or women who lived average lives; books that allowed them to witness the past through the eyes of someone like them.

Popular History Books Use Plain, Evocative Language

Language has the power to evoke ideas, images, and emotions. The writers of popular history books embrace language. They use words and idioms that enliven or humanize the people and events they write about.

I love scholarly history books, but comparatively the language within them is flat. Many scholars focus more on the point they are trying to make rather than on how they express their point. Popular history writers pay more attention to expression.

Popular history writers also use plain language, short sentences, and idioms.

You won't find the "technical or specialized parlance of a specific social or occupational group" in a popular history book. You also won't find copious citations or in-text references to other historians' books.*

Popular history writers write like they talk.

Scholarly writers often write like distant narrators who use big words and complex sentences.

Popular History Books Make Judgement Calls

Writers of popular history books pass judgement. Historians mince words.

Often, scholarly authors use language that both implies judgement and offers them plausible deniability for such thoughts.

For example, a popular history author writes "Benjamin Franklin was a womanizer." An author of a scholarly work pens "Benjamin Franklin seemed to have an affinity for women given all of the flirtatious language in his surviving correspondence."

Readers view authors as subject experts. They want to know the writer's opinion on the topic or person at hand. A preference at odds with scholars' training.

Conclusions

I offer the above as observations on the patterns I see.

I freely admit that while reading some popular history books my eyes have rolled and audible, exasperated sighs have passed through my lips.

I think popular history writers are on to something with people and the use of plain, evocative language.

If writers of scholarly history books took these techniques and applied them to their studies of everyday men and women, I believe we could see a resurgence of scholarly historical research on bestseller lists and on the bookshelves of non-university bookstores.

*Encyclopedia Britannica, "jargon."