This week I am taking “Historiann” Ann M. Little’s Challenge.

Inspired by James McPherson’s Q & A in The New York Times Sunday Book Review, Little decided to answer the same questions The Times posed to McPherson. She posted her responses on her blog “Historiann: History and Sexual Politics, 1492 to the Present” and encouraged her readers to do the same.

This week I am taking “Historiann” Ann M. Little’s Challenge.

Inspired by James McPherson’s Q & A in The New York Times Sunday Book Review, Little decided to answer the same questions The Times posed to McPherson. She posted her responses on her blog “Historiann: History and Sexual Politics, 1492 to the Present” and encouraged her readers to do the same.

In this post you will discover what my answers are to The New York Times Book Review interview questions.

The Interview

What books are currently on your night stand?

Presently, I have 7 books on my nightstand:

1. Gregory O’Malley, [simpleazon-link asin="1469615347" locale="us"]Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807[/simpleazon-link]

Presently, I have 7 books on my nightstand:

1. Gregory O’Malley, [simpleazon-link asin="1469615347" locale="us"]Final Passages: The Intercolonial Slave Trade of British America, 1619-1807[/simpleazon-link]

2. Ian Mortimer, [simpleazon-link asin="1439112908" locale="us"]The Time Traveler's Guide to Medieval England: A Handbook for Visitors to the Fourteenth Century[/simpleazon-link]

3. Ian Mortimer, [simpleazon-link asin="014312563X" locale="us"]The Time Traveler's Guide to Elizabethan England[/simpleazon-link]

4. Marcus Aurelius, [simpleazon-link asin="0812968255" locale="us"]Meditations: A New Translation[/simpleazon-link]

5. Mark Satterfield, [simpleazon-link asin="1939529786" locale="us"]The One Week Marketing Plan: The Set It & Forget It Approach for Quickly Growing Your Business[/simpleazon-link]

6. Lawrence Hill, [simpleazon-link asin="B00LLOW318" locale="us"]The Book of Negroes[/simpleazon-link]

7. Allegra di Bonaventura, [simpleazon-link asin="0871407760" locale="us"]For Adam's Sake: A Family Saga in Colonial New England[/simpleazon-link]

What was the last truly great book you read?

In terms of history, the last great book I read was John Demos’ [simpleazon-link asin="0679759611" locale="us"]The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America[/simpleazon-link]. This well-written history narrative provides excellent insight into how an historian's mind works. It is a history book that tells a gripping story that reads like a detective novel.

[simpleazon-image align="left" asin="0679759611" locale="us" height="400" src="http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51w7FF-cTlL.jpg" width="225"]The Unredeemed Captive tells the story of Eunice Williams and her family. On the night of February 29, 1704, French-allied Native Americans raided the town of Deerfield, Massachusetts. The raid came early in Queen Anne's War (1702-1713), the second out of four wars waged between France and England for domination of North America. The raiders kidnapped Eunice Williams and many of her family members during the attack. In fact, the Native Americans went to Deerfield with orders from New France's governor to take Williams' father, Reverend John Williams, because he would fetch a high value in any prisoner exchange between New France and New England. Although the Governor of Massachusetts Bay arranged for the redemption of all of the Williams family members, the Native Americans had adopted 4-year-old Eunice and refused to part with her. As a result, Eunice became an adopted member of the Kahnawake Mohawk people. She grew up as both a Mohawk and as a French-speaking Catholic, a fate almost worse than death for her Puritan family.

Demos spends much of the book sorting out the knowns and unknowns of Eunice's life as a Kahnawake. Sparse documentary evidence about Eunice's life causes Demos to discuss theories or speculations about what Eunice's life as a Mohawk must have been like. He bases his theories and speculations on first-hand accounts of what the village looked like, how the Kahnawake lived and worked, and the Mohawks' process of captive adoption. Demos admits that much of his evidence comes from accounts biased with European prejudices.

In sharing his thought process throughout The Unredeemed Captive, Demos shows how the mind of an historian works. Throughout the book Demos demonstrates how historians weigh evidence. He gives a lot of weight to evidence that specifically documents Eunice and notes how and why some supporting evidence such as letters between family members or the captive narratives of others do not offer as reliable evidence.

Who are the best historians writing today?

In alphabetical order: Colin G. Calloway, John Demos, Alan Taylor, and Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, to name just a few.

What’s the best book ever written about American history?

This question is too broad to answer and I am also not sure that it should be answered in such general terms. Historical works reflect the interests of the period that historians wrote them in. Each generation has produced history books that contemporary readers deemed interesting, well-researched, and well-argued.

[simpleazon-image align="right" asin="0743223136" locale="us" height="300" src="http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/517oIyvrNDL.jpg" width="207"]Do you have a favorite biography of a Revolutionary War-era figure?*

David McCullough’s [simpleazon-link asin="0743223136" locale="us"]John Adams[/simpleazon-link]. I haven’t read a biography in a while, but I couldn’t put this thick tome down when I read it many years ago. Also, I took away more information from this book than the details of John Adams’s life; this book taught me about the power of relating American history through the lives of individuals. Readers like to live vicariously through the people they read about. John Adams taught me that the one major key to making American history accessible is to find a compelling character(s) and base a narrative around that person(s).

What are the best military histories?

E. Wayne Carp’s [simpleazon-link asin="0807842699" locale="us"]To Starve the Army at Pleasure: Continental Army Administration and American Political Culture, 1775-1783[/simpleazon-link]. Published in 1984, this book reminds readers that military victory often hinged on the ability of the government to supply its troops. The Continental Army lost battles, and Canada, because it was ill-equipped with food, shelter, firewood, and medicine. Carp attributes the poor supply of the Continental Army to the discord between the Continental Congress’ adherence to republic ideology and the actions needed to supply its army. This book places military histories of War for Independence battles in perspective.

What are the best books about African-American history?

Presently, I am enjoying Gregory O’Malley’s [simpleazon-link asin="1469615347" locale="us"]Final Passages[/simpleazon-link]. O’Malley explores the intercolonial slave trade, the transshipment of enslaved Africans that took place after the Middle Passage. O’Malley argues that more than those who shipped slaves from Africa, the men who participated in the intercolonial slave trade viewed slaves as commodities rather than as human beings, which he demonstrates in how the traders reacted to the slave market, imperial boundaries, and external forces such as captures by pirates or privateers.

Another work that has stayed with me is Sylvia Frey’s [simpleazon-link asin="0691006261" locale="us"]Water from the Rock: Black Resistance in a Revolutionary Age[/simpleazon-link]. Frey reveals the tough choices African-American slaves had to make during the Revolution. The Revolution offered slaves opportunities to resist slavery. It also presented male slaves with the chance to fight for their freedom. However, slaves had to trust that British and Patriot army officials would honor their offer to free them. They also had to contend with the military strategies of both armies. The Revolution placed most slaves in a difficult situation as attempting to stay neutral or choosing the wrong side might worsen their condition rather than bring freedom.

During your years of teaching, did you find that students responded differently over time to the history books you assigned?

Presently, I do not teach history in a college classroom. When I did teach, I taught at a community college that did not allow me to assign books outside of the required textbook.

[simpleazon-image align="left" asin="0394800168" locale="us" height="300" src="http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51Kgqd4kiNL.jpg" width="235"]What kind of reader were you as a child?

I read a fair amount as a child. The first book I read on my own was Dr. Seuss’s [simpleazon-link asin="0394800168" locale="us"]Green Eggs and Ham[/simpleazon-link]. As I grew older I came to enjoy historical fiction, how-to, and choose-your-own-adventure books. In high school I read a lot of biographies and history books. I wasn’t a very discerning reader; I picked up whatever American Revolution book was on the Barnes & Noble table or library display. Today, I prefer the same genres: history, biography, historical fiction, and how-to. I have also become a very picky reader. If a book is not well-written or does not have a good story, I put it down and move on.

If you had to name one book that made you who you are today, what would it be?

During the summer of 2001, I read 3 books that influenced my decision to become a professional historian: Bernard Bailyn’s [simpleazon-link asin="0674443020" locale="us"]The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution[/simpleazon-link], T.H. Breen’s [simpleazon-link asin="0691089140" locale="us"]Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution[/simpleazon-link], and David McCullough’s [simpleazon-link asin="0743223136" locale="us"]John Adams[/simpleazon-link]. I had just finished my freshman year at Penn State and spent the summer as an intern for the Boston National Historical Park. Ranger Richard Lehmann told me that if I wanted to know about the history of the American Revolution I should read both Bailyn and Breen. These works served as my introduction to analytical history and deep-thinking about the Revolution. It was an intellectual feast. McCullough’s John Adams taught me that history books can be fun to read (and that people will read them) if centered on a compelling historical figure.

If you could require the president to read one book, what would it be?

I would love for members of all three branches of government to (re)read George Washington’s "Farewell Address," which discusses Washington's fears over partisanship. With that said, I am not sure they are inclined to understand the message that partisanship can hinder good governance.

You are hosting a literary dinner party. Which three writers are invited?

David McCullough, Stephen King, and George R.R. Martin. This would make for an interesting evening, wouldn’t it? An historian and two novelists. However, I would love to discuss how they found their writer’s voice and how they developed their knack for descriptive and compelling storytelling. All three authors are masterful storytellers. Also, I would love to hear them share their insights on what it was (is) like to have their work turned into a television script.

I can dream that I will write a work of history that will be compelling enough to warrant a TV mini-series, can’t I?

Disappointing, overrated, just not good: What book did you feel as if you were supposed to like, and didn’t? Do you remember the last book you put down without finishing?

[simpleazon-image align="right" asin="0226306526" locale="us" height="300" src="http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/51eSze2DNpL.jpg" width="200"]

Stephen Greenblatt’s [simpleazon-link asin="0226306526" locale="us"]Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World[/simpleazon-link]. I read it during my first year of graduate school. I wrote such a scathing review of it, my advisor made me re-write it. On the plus side, my experience with this book provided me a with valuable lesson on how to write a critical, but fair book review.

What books are you embarrassed not to have read yet?

If you had asked me this question last week, I would have said John Demos’ [simpleazon-link asin="0679759611" locale="us"]The Unredeemed Captive[/simpleazon-link], but I just finished it. (It is an excellent read.)

Today, I am embarrassed that I still haven’t read Alan Taylor’s [simpleazon-link asin="039334973X" locale="us"]The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772–1832[/simpleazon-link]. It has been out for a year and it won the Pulitzer Prize. Additionally, Alan is a good friend and I love to read his books. Fortunately, Alan has agreed to talk about The Internal Enemy on Ben Franklin’s World: A Podcast About Early American History in January 2015, which means I will read it soon.

What do you plan to read next?

My new podcasting career has placed a lot of history books on my list. My next history read will be Don Hagist’s [simpleazon-link asin="1594162042" locale="us"]British Soldiers, American War: Voices of the American Revolution[/simpleazon-link]. Afterwards I will read Ken Miller’s [simpleazon-link asin="0801450551" locale="us"]Dangerous Guests: Enemy Captives and Revolutionary Communities during the War for Independence[/simpleazon-link].

Share Your Story

Share Your Story

How would you answer each of these questions?

Please respond in the comments section or on your own blog. If you post your answers on your blog, please share your link.

*I adapted this question to suit my own historical interests.

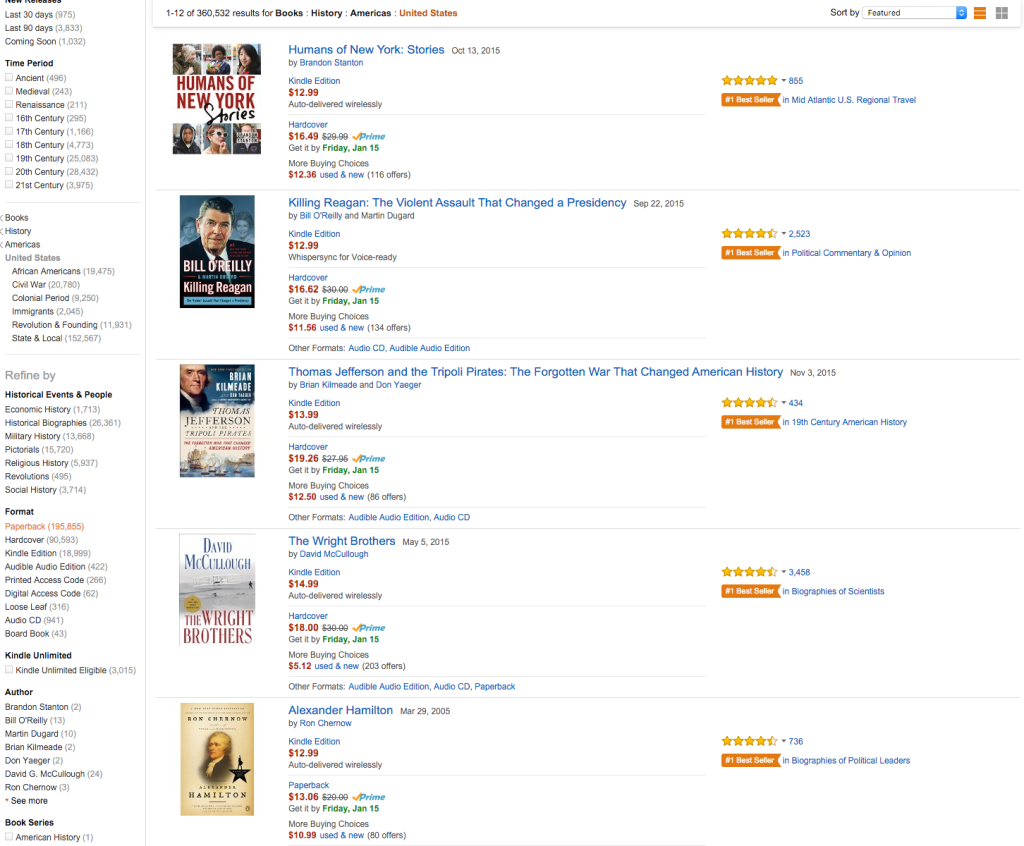

What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for Ben Franklin's World.

What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for Ben Franklin's World.