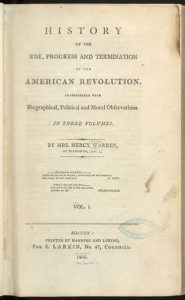

I've been digging into the earliest histories of the American Revolution. Specifically David Ramsay's The History of the American Revolution in Two Volumes (1789) and Mercy Otis Warren's The Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution (1805).

Ramsay's history contains 667 pages, Warren's history 700 pages.[1] In all of those pages, Ramsay devotes almost two pages to the Articles of Confederation, Warren a single, short paragraph.[2]

I've been digging into the earliest histories of the American Revolution. Specifically David Ramsay's The History of the American Revolution in Two Volumes (1789) and Mercy Otis Warren's The Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution (1805).

Ramsay's history contains 667 pages, Warren's history 700 pages.[1] In all of those pages, Ramsay devotes almost two pages to the Articles of Confederation, Warren a single, short paragraph.[2]

What does it mean that the first historians of the American Revolution--a man and woman who lived through and experienced the event--devoted so little time and space to the United States' first constitution?

In fairness to Ramsay, he does summarize why the Second Continental Congress drafted the Articles of Confederation: "the act of independence did not hold out to the world thirteen sovereign states, but a common sovereignty of the whole in their united capacity. It therefore became necessary to run the line of distinction, between the local legislatures, and the assembly of the states in Congress." (332) He also reflects on the powers granted to the "assembly of states in Congress" by the Articles of Confederation.

As Ramsay recounts the powers the Articles of Confederation granted to the new national congress, he also reflects on why aspects of the confederation government proved weak: The new government did not have the power to regulate trade because Americans had so little experience trading with foreign powers on their own; the framers of the Articles didn't know they needed the power to regulate trade. The confederation government lacked a "power of compulsion" [power to tax] on the states because "the system of federal government was...more calculated for what men then were, under these circumstances, than for the languid years of peace, when selfishness urusped the place of public spirit, and when credit no longer assisted, in providing for the exigencies of government." (333)

Ramsay may have included the Articles of Confederation in his history, but his account is short and it doesn't attempt to describe the debate, conflict, and compromise that informed the drafting and ratification of the Articles of Confederation.

Why do these early histories lack details about the Articles of Confederation and how they came to be?

I can think of some possibilities:

Both Ramsay and Warren relied on the papers and correspondence of friends as source material for their histories. Did they largely omit the drafting and ratification of the nation's first government from their histories because their friends and correspondents weren't those who had participated in the drafting and ratification of the Articles? It's a possibility, but one I don't think will turn out to be the case.

Could it be that the absence of the Articles of Confederation in these histories speaks to the fact that there was so much going on with the War for Independence that Americans were too distracted to care or notice the ratification of their first national constitution on March 1, 1781? This could be true, in part. I know from my work on the Revolution in Albany that on the ground most people were more concerned with survival than with the activities of a faraway congress.

Or perhaps the reason why Warren and Ramsay devoted so little time and space to the Articles of Confederation is that both published their histories with nationalistic goals and after the ratification of the Constitution of 1787. In fact, Ramsay purposely waited to publish his history until after the states had ratified the Constitution.

Ratification of the Constitution complicated the history of the Articles of Confederation, especially for the nation's first historians. Both Warren and Ramsay's histories feature chronological accounts of the Revolution. Their histories read as "this event happened and then this event happened and then this event happened" with splashes of commentary thrown in.

Both historians strove to use early American history as a way to unite the new nation. They recognized that Americans needed to form an identity apart from Great Britain and British traditions. They attempted to unify their fellow Americans by writing histories that the new nation could be proud of. Sure the United States failed throughout the course of the American Revolution, but Americans learned from their mistakes and overcame the odds to secure their independence. These histories have political and moral points and these points are supposed to be uplifting.

As Ramsay's brief attempt to incorporate the Articles of Confederation into his history demonstrates, the Articles don't fit neatly within the framework of these early nationalist histories. The story of the Articles highlights conflict and dissension. States and regions argued over whether the state or national government should have supreme sovereignty; how lands should be divided and governed; how citizens and states should be taxed. It took three years, lots of compromise, and the threat of a British invasion of Maryland for the states to unanimously ratify the Articles and put the constitution into effect.

In 1805, the story of the Articles was ill-timed. It contained too much discord to recount at a time when Americans were still trying to unite behind the Constitution of 1787. No one yet knew if the Constitution of 1787 would persist and whether the United States would survive as an independent country. This uncertainty would have made it difficult for these nationalist historians to grapple with the history of the Articles of Confederation.

Regardless of why Ramsay and Warren largely omitted the Articles of Confederation from their histories, the fact that they largely left the constitution out of their histories leaves me to wonder if it's their omission that has caused it to be absent from so many subsequent histories of the American Revolution and early United States.

Notes

[1] Warren, Mercy Otis. The History of the Rise, Progress, and Termination of the American Revolution. Edited by Lester H. Cohen. 2 vols. Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1988; Ramsay, David. The History of the American Revolution in Two Volumes. Edited by Lester H. Cohen. 2 vols. Indianapolis: Liberty Classics, 1990.

[2] If you're curious, Warren had this to say about the Articles of Confederation in her one paragraph: "A solemn confederation, consisting of a number of articles by which the United States should in future be governed, had been drafted, discussed, and unanimously signed by all the delegates in congress, in the month of October, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-six. This instrument was sent to each legislature in the thirteen states, and approved and afterwards ratified by the individual governments. After this, the congress of the United States thought proper to appoint commissioners to the court of France, when fortunately a loan of money was negociated [sic] on the faith of the United States, and permission obtained for the reception of American ships of war, and the sale of prizes that might be captured by them, and carried into any of the ports of France." pg 198. Note that Warren gave the wrong date. Congress signed the Articles of Confederation and sent them out to the state legislatures in November 1777, not October 1776.

Since January 2016, I have been traveling across the United States speaking about history, podcasting, and digital media at conferences, events, and interviews.

The experience has revealed that people have 3 key questions for me:

Since January 2016, I have been traveling across the United States speaking about history, podcasting, and digital media at conferences, events, and interviews.

The experience has revealed that people have 3 key questions for me: It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with

It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with  On March 3, 2016, I explored the idea of whether it makes sense to create a

On March 3, 2016, I explored the idea of whether it makes sense to create a  Podcasts are hot right now.

Podcasts are hot right now.