This month, I’m sponsoring 10 graduate students as Omohundro Institute Associates. As an OI Associate you will receive a paper copy of the William and Mary Quarterly, a 20 percent discount on OI and UNCPress books, and invitations to OI seminars, conferences, and our not-to-be-missed AHA and OAH receptions. But MOST importantly, you will gain access to one of the best scholarly communities in the world.

In 2004, my undergraduate mentor and advisor, William Pencak, introduced me to my first scholarly community. He told me that as a historian I should have twin goals in my career: produce high-quality work the field can benefit from and be a good, collaborative colleague. He told me being an active member of the larger scholarly community would help me achieve both goals. He then sponsored my first conference paper and my first membership to a professional organization to introduce me to this broader community.

Bill Pencak was a generous colleague who gave this advice to many of his students and modeled it so we could follow his example. Bill’s advice stands among the best professional advice I’ve ever received and it has played a big and crucial role in my career. The scholarly community Bill introduced me to through my first professional organization membership has provided me with more knowledge about our early American past and has given me opportunities to build my professional network. It’s a network that has come in handy so many times over the years. The people within it have helped me as a graduate student, as an independent scholar in search of a place within the profession, and as a working historian once I found my place.

In fact, my journey to the Omohundro Institute started because Bill Pencak introduced me to the importance of scholarly community. In 2007, I briefly met another scholar at a conference. This short encounter proved to be enough that I felt comfortable talking to this person when we met again in different venues in 2012 and 2013. And because I had conversed with this person in 2012 and 2013, I felt I could reach out with a request for real assistance when Ben Franklin’s World started to take off and I needed to know how to transform it from a hobby into a professional publication. This professional connection came from my active membership in a scholarly community and it led me to the Omohundro Institute in 2014.

Now in case you aren’t familiar with the rest of my story, the people of the Omohundro Institute generously agreed to share their knowledge with me on what it takes to build a professional publication. They also further offered to help me implement and adapt their advice in ways that worked for my project. Today, Ben Franklin’s World stands as the reigning best history podcast, a podcast that performs in the top 7 percent of all podcasts, and as a publication that is achieving its goal to make great scholarly history available to people outside of the profession.

All of this success happened because of a chance meeting I made while taking Bill’s advice to become an active member of the scholarly community.

My intent with this drive is twofold: First, I want to pay back Bill’s kindness and honor his memory; Bill passed away in 2013. My hope is that if I introduce you to the Omohundro Institute’s scholarly community you will do what Bill gave me the opportunity to do: read its journal, share your ideas at its conferences, attend its receptions, and work on building your professional network.

My second goal is quite selfish: I want you to join my primary scholarly community because it benefits me and my colleagues. Many of the great ideas we get for new projects and how we can improve and expand our current projects come from OI Associates. So, I want to hear about your ideas at our conferences and meet you at our receptions. I want you to enjoy the ideas and examples of high-quality work the OI publishes because they will help you generate more ideas. Ultimately, I want to introduce you to this community because I think once you join us, you will stick around for the remainder of your career and help us with our mission to support the production of high-quality scholarship and to get that scholarship out into the world where it can be useful.

So, if you are a graduate student and would like to join the OI community as an Associate, I will sponsor your membership. Send me an e-mail. Please tell me who you are, what you are working on, which graduate program you are affiliated with, and where the OI can mail your WMQ.

It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with

It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

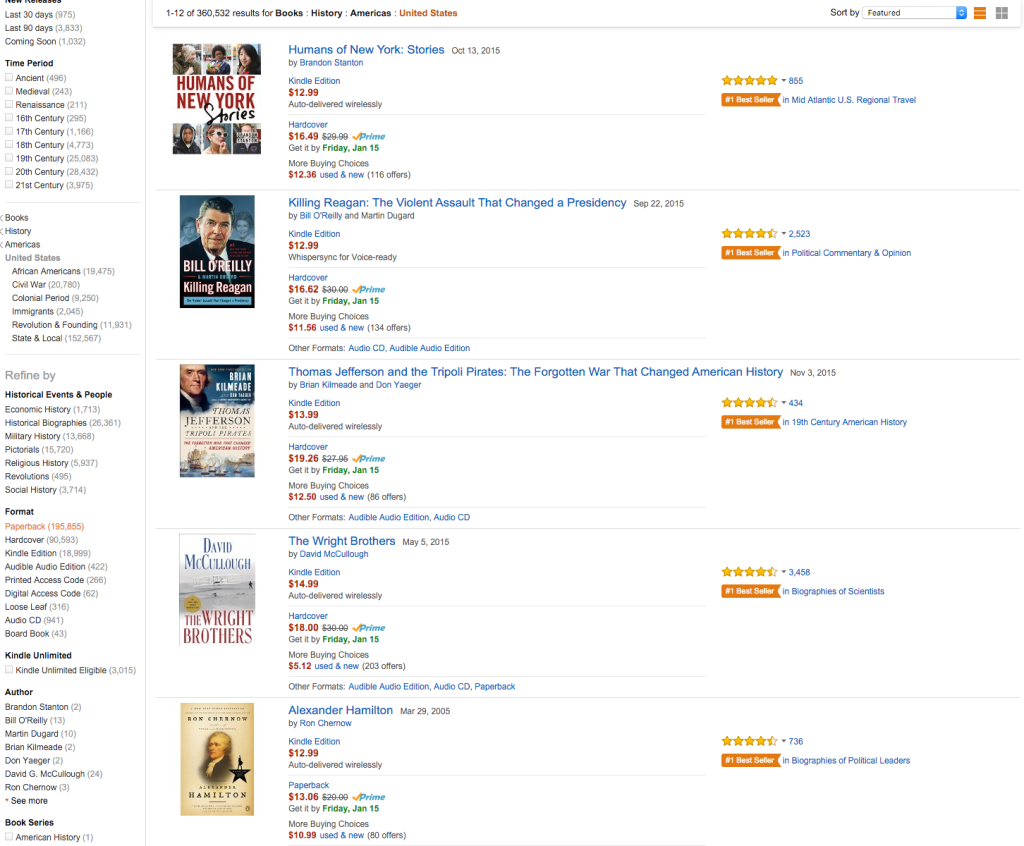

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with  What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for

What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for