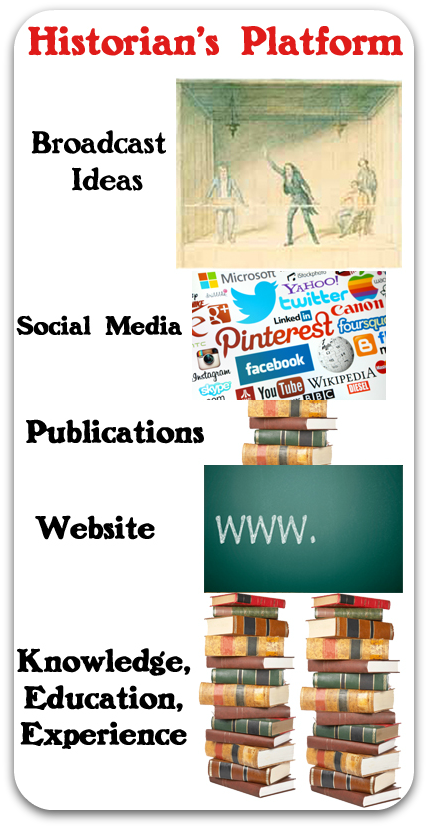

Are you thinking about adding a podcast to your historian’s platform?

I thought it would be interesting to share how “Ben Franklin’s World: A Podcast About Early American History” has fared as a method to communicate the work of professional historians to the history-loving public.

Are you thinking about adding a podcast to your historian’s platform?

I thought it would be interesting to share how “Ben Franklin’s World: A Podcast About Early American History” has fared as a method to communicate the work of professional historians to the history-loving public.

In this post, you will discover how Ben Franklin’s World has performed during its first four months.

Brief Overview of Launch

I launched Ben Franklin’s World in two phases: a soft launch and a hard launch.

Soft Launch

The soft launch took place on the benfranklinsworld.com website.

On October 7, 2014, I posted the first four interview episodes plus my short pilot episode; the pilot offers a brief explanation of who I am and why I started the podcast.

Until early December 2014, these episodes could only be accessed from benfranklinsworld.com.

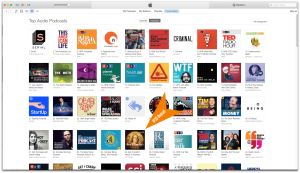

The soft launch gave me time to tweak the show and build a catalog of 8-10 episodes before I listed it on iTunes, the largest podcast directory.

Podcast experts recommend debuting a podcast on iTunes with 5-10 episodes.

Launching with several episodes allows new listeners to download multiple episodes. (Many podcast listeners like to binge listen to new shows.) This strategy also provides enough content for your podcast to generate the download numbers it needs for placement in iTunes' “New & Noteworthy” sections.

“New & Noteworthy” sections provide prominent placement within specific categories and/or the entire iTunes store. Placement in "New & Noteworthy" helps listeners discover your podcast faster; think free advertising.

Hard Launch

Hard Launch

The hard launch took place on December 2, 2014 when Apple accepted my submission and listed Ben Franklin’s World on iTunes.

New episodes appeared every other Tuesday until December 30, 2014, when Ben Franklin’s World became a weekly show.

By starting as a twice-monthly program, I created positive buzz for the podcast and gave myself time to build a sufficient store of new episodes to support a weekly show.

Strategy Results

This two-part launch strategy worked.

Ben Franklin's World built a small, but dedicated following of friends, family, and people who found the show via social media between October and December.

Early listeners provided useful feedback, which I used to tweak the show. They also helped to elevate the profile of the show when it launched on iTunes.

After iTunes listed Ben Franklin's World, I sent an e-mail to the 30+ people on my e-mail list. I informed them that they could now find the show in iTunes and asked them to provide honest ratings and reviews. (Apple uses ratings and reviews to help determine which shows to place in its "New & Noteworthy” sections.)

Their downloads, ratings, and reviews helped place Ben Franklin’s World in the “New & Noteworthy” section of the history category before the end of its first week on iTunes.

Placement in "New & Noteworthy" also boosted the profile of Ben Franklin’s World. Show download numbers went from single and double-digit downloads per day to 100 and 200 downloads per day.

On December 28, 2014, the podcast took off.

On December 28, 2014, the podcast took off.

The show received placement in the “New & Noteworthy” section for the entire iTunes store and two or three times appeared among the top 10 shows in “New & Noteworthy."

The result: December 28, marked my first 1,000+ download day with 1,304 downloads. On December 29, the show had 2,548 downloads. The peak came on December 30 with 3,545 downloads in a single day!

Throughout January, Ben Franklin’s World did not have a sub-1,000 download day.

Peak days always came on Tuesdays (new episode release days) when instead of having a 1,000+ download day, the show had a 2,000-2,500+ download day. Release days always put Ben Franklin’s World among the top 200 podcasts in the overall store.

Apple allows new podcasts about 8 weeks of eligibility for its “New & Noteworthy” categories. Ben Franklin’s World enjoyed great placement for exactly 8 weeks.

Downloads Post “New & Noteworthy"

On February 1, 2015, iTunes removed Ben Franklin’s World from “New & Noteworthy.”

Download numbers have dropped a bit, but I am very pleased with the performance of this young program.

Download numbers have dropped a bit, but I am very pleased with the performance of this young program.

New episodes still experience 2,000+ downloads on release day and numbers stay above 1,000 downloads per day until about Thursday or Friday when they dip into the 900-500+ downloads per day range for the rest of the week.

With that said, new episodes still reach 5,000 downloads in 7-14 days.

As of Thursday, February 12, 2015, at 9:57 am, listeners have downloaded episodes of Ben Franklin’s World 83,494 times.

Although downloads do not equal number of listeners, they illustrate that a lot of people are choosing to spend 35-55 minutes each week discovering the great work that academic and public historians are conducting in early American history.

In the near future, I would like to increase the reach of Ben Franklin's World and its daily download numbers so the podcast once again enjoys 1,000+ downloads per day. I have ideas for how I can achieve this feat and I will share my strategies for promotion in future posts.

Conclusions

I enjoy podcasting and the medium has provided me with many benefits.

First, podcasting has helped me achive my goal: It has enabled me to start bridging the gap between professional historians and the history-loving public.

Ben Franklin’s World has created a wider public awareness about my colleagues' historical research.

Second, podcasting has expanded my professional and social networks.

Each week, I have a meaningful conversation with a different colleague, often someone I have not had the chance to meet in person.

I also receive several e-mails per week from listeners who tell me how much they enjoy the podcast and learning about the work of its guest historians.

Third, my work as a podcaster has allowed me to become a more well-read historian.

Since August, I have read one history book a week that does not pertain to my research or my sepcific interests in early American history.

I look forward to continuing this new professional adventure.

What Do You Think?

What Do You Think?

Have you considered creating a podcast? Do you have questions about podcasting that I could help you answer?