If you have attended a conference during the past two or three years you have likely witnessed the following scene: three to four panelists at the front of the room reading their papers one-by-one, while several people in the audience alternate between watching the presenters and looking down at their smartphones or tablets while frantically texting.

This is the scene of many #Twitterstorians at work live-tweeting a conference.

If you have attended a conference during the past two or three years you have likely witnessed the following scene: three to four panelists at the front of the room reading their papers one-by-one, while several people in the audience alternate between watching the presenters and looking down at their smartphones or tablets while frantically texting.

This is the scene of many #Twitterstorians at work live-tweeting a conference.

In this post, you will find tips and tricks for how you can live-tweet a conference panel as well as why I think conference tweeting has become a necessary part of the profession.

Why Tweet a Conference Panel

Tweeting conference panels has become a mainstream activity at professional conferences.

Conference tweets help spread new ideas, start conversations about those new ideas, and allow colleagues who couldn’t attend to stay up-to-date with the latest professional information.

Conference tweets also serve as a powerful public relations tool. Anyone interested in a particular profession can gain insight into the inner-workings of that profession by following tweets from a professional organization’s annual conference.

In the case of History, not only does tweeting information from a conference help fellow historians gain insight into what areas colleagues are exploring, but it helps non-historians gain insight into the work historians do.

Conference Tweet Etiquette

Caution: Tweeting conference panels is important work that should not be undertaken lightly. Live-tweeting a conference requires a high-level of mental focus. To tweet well you must really pay attention to the presenters and the ideas they convey.

Conference Tweet Etiquette

There are several stated and unstated rules you should follow if you want to be a successful and professional conference tweeter.

1. Know Your Venue: Tweeting from conferences has become an accepted professional practice. However, it would be unprofessional to tweet from a seminar that has a reputation as a workshop for fresh ideas.

2. Use the Hashtag: Nearly every conference has an official hashtag that you should use when you tweet. The hashtag serves several purposes:

2. Use the Hashtag: Nearly every conference has an official hashtag that you should use when you tweet. The hashtag serves several purposes:

1. It tells your followers that you are at a conference.

2. The hashtag allows anyone interested in the conference to follow tweets in context and in sequence.

3. Hashtags make it easier for conference organizers to aggregate tweets.

4. It is a powerful networking tool that will connect you with other conference-goers.

3. Give Credit: Always attribute the ideas of a presenter to that presenter. All tweets containing another’s idea should contain their name. Proper etiquette requires that you first tweet their full name, affiliation, and paper title (sometimes this requires more than one tweet) and then use either their last name or twitter handle (preferred if they have one) at the start of each subsequent tweet.

4. Number Your Tweets: If you need more than 140 characters to tweet a presenter’s idea, number your tweets. The number should be at the end of the tweet and in parentheses: (1), (2), (3). You should number your tweets as a sequence if you know how many tweets you need to convey an idea: (1/3), (2/3), (3/3). Numbering your tweets helps followers know that your tweets are part of a sequence.

5. Issue Corrections: Tweeting a conference panel is fast-paced work. No one performs it flawlessly. If you discover that you mis-tweeted a panelist’s ideas, delete your original tweet and issue a corrected tweet.

You should consider letting panelists know that you are willing to issue corrections. You can tell them in person or tweet at the end of a panel, or the conference, that you will gladly correct a mistake if someone finds one.

6. Identify Yourself If Requested: Some conference organizers request that you introduce yourself as a #Twitterstorian or tweeting attendee to the panelists before a panel starts. In my experience, this happens only at academic conferences and more of these conferences are rendering this introduction unnecessary by issuing badges that say “I Tweet” to those who tweet.

7. Do Your Best: Conference tweets represent presenters' ideas and convey an image of you as a professional historian to colleagues and the outside world. Do your best to convey ideas, the profession, and you accurately.

How To Tweet A Panel

How To Tweet A Panel

There are two ways to tweet a conference panel: live or after the fact.

Those who live-tweet use their smartphones, tablets or laptops to type tweets as panelists speak. Some conference attendees prefer to tweet after they have paid attention to the entire panel and digested its ideas. In both cases, you should introduce and attribute your tweets to the person and paper where they came from.

How to Live Tweet A Conference Panel

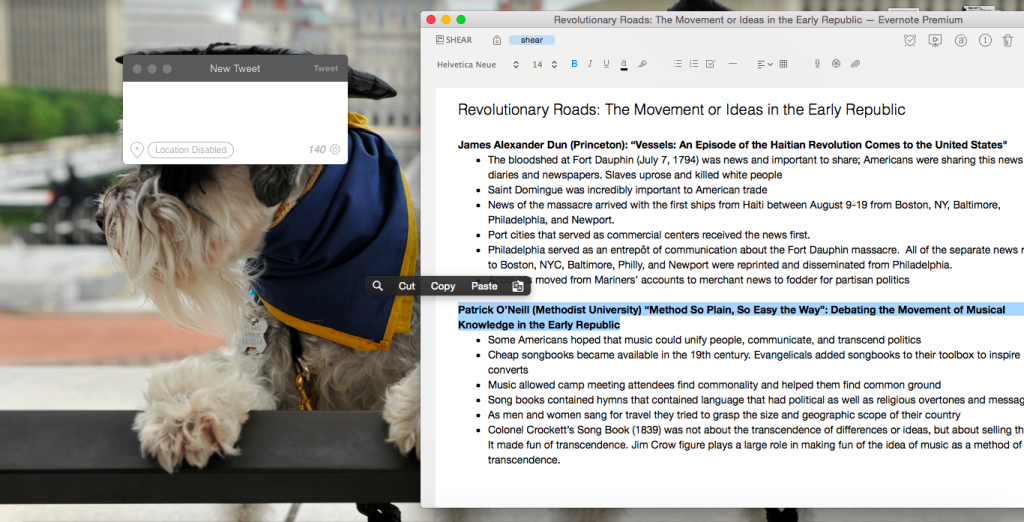

Many Twitterstorians live-tweet from their smartphones or tablet devices. I prefer to tweet from my laptop because I can take all the notes I want and then cut and paste what I want to tweet with ease.

I also prefer to live-tweet from my laptop because I type much faster on a full-sized keyboard. Capturing notes on my laptop allows me to focus more on ideas instead of on whether my thumbs hit the right key on a touchscreen device. Additionally, typing notes enables me to capture the context of an idea and better judge if and how it should be tweeted.

My Live-Tweet Workflow

Equipment/Tech: Laptop, smartphone, power cords, Evernote (my favorite note-taking app) and Tweetbot (my favorite Twitter app).

Step 1: Sit by a power outlet. Whenever possible, I show up to a panel early and sit near an outlet. This allows me to charge and save my laptop and smartphone batteries for rooms where I cannot sit by an outlet.

Step 2: Connect to the internet. History conferences have a spotty record when it comes to providing free WiFi. Many #Twitterstorians tweet from their smartphones because they are portable and already connected to the internet. I prefer to work on my laptop.

Before the panel begins, I either connect to the free WiFi or create a private WiFi hotspot for my laptop with my smartphone.

Step 3: Make note of speakers, paper titles, and twitter handles. I try to do this the night or morning before, but if this doesn’t work, I pull out my conference program, flip to the appropriate page, and place the open page on the floor in front of me or on the chair next to me (if available).

Although, conference programs tell you the names and proper spellings of the speakers and their paper titles, I have yet to see one include the presenters' Twitter handles. I perform a quick search to see if I can locate one. Often I attribute tweets using the presenter's last name.

Step 4: Use shortcuts/hotkeys. Hotkeys or shortcuts won’t help you on a smartphone or tablet, but they can simplify your live-tweet workflow on a laptop.

If you are logged into Twitter you can launch a new tweet box by pressing [N].

I set [option + /] as my hotkeys for Tweetbot. I prefer to use Tweetbot because I can launch a new tweet box while I take notes in Evernote.

Other shortcuts/hotkeys you might find helpful are those for cut and paste. On a Mac the keyboard shortcut for cut is [command+ c]. Use [command+ v] for paste.

Step 5: Tweet.

Conclusion

Conclusion

I started tweeting conference panels to help colleagues who could not attend the conference. However, the more I have tweeted and interacted with non-conference attendees, the more I have realized that conference tweets don’t just help fellow historians catch a glimpse of the ideas being discussed, they help anyone interested in history gain insight into the inner-workings of the historical profession. This is an aspect of conference tweeting that the profession should welcome. The more people who understand what we do and why our work is important, the easier time history departments and organizations will have finding funding and students.

Share Your Tips!

Do you live-tweet conference panels? Do you have helpful tips to share?