Jointly authored by Liz Covart and Joseph Adelman

Twitter is a deceptively simple tool. With just 140 characters to work with, it can seem at times like it takes barely any work at all to come up with a tweet. There's not much room to say anything, right? But trying to say something meaningful in 140 characters is an art, and takes practice and consideration.

Jointly authored by Liz Covart and Joseph Adelman

Twitter is a deceptively simple tool. With just 140 characters to work with, it can seem at times like it takes barely any work at all to come up with a tweet. There's not much room to say anything, right? But trying to say something meaningful in 140 characters is an art, and takes practice and consideration.

From our conversations, we have realized that most of the guides to using Twitter focus primarily in generating a follower base and otherwise building an audience. That's worthwhile, of course, but it means that there is room for something that discusses how to craft an individual tweet, including how to use links, hashtags, and other tools in tweets.

We hope this guide will prove helpful for individual Twitter novices, but also for classes and other group projects where not everyone knows or understands how to write tweets.

Twitter Anatomy

To begin, here are some of the basic mechanics of how Twitter works:

- Tweets can be no more than 140 characters, including spaces and punctuation as well as any links or images you include.

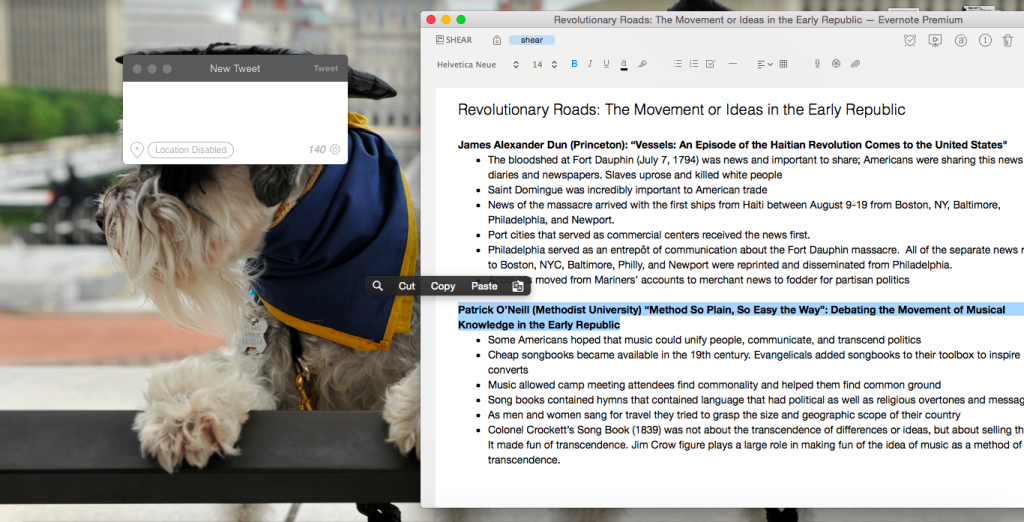

- If you tweet from Twitter, the service will automatically shorten the URL you wish to share down to 24 characters. All you need to do is cut or copy the URL you want to share from your browser and paste it into your new tweet box in Twitter. [1]

- After you use a shortened link, you will have approximately 118 characters left for your tweet.

- Twitter will automatically embed any image you attach to a tweet; the link Twitter creates takes up 23 characters. Twitter allows users to add up to 4 images to each tweet. After your first image, additional photos do not count against your character limit.

- You also want to leave 10-40 characters free, if possible, as research shows tweets with less than 140 characters receive more engagement.[2]

- You can use a hashtag to link your tweet to others on a similar topic. Hashtags are the words with # in front of them. They let users know that a tweet is part of a larger conversation by defining either the audience or topic the tweet addresses. For example, a tweet with #Twitterstorians is a tweet for historians on Twitter. #AmRev denotes a tweet about the American Revolution. See the History Hashtags list for a comprehensive list of history hashtags.

- You can include other feeds in your tweet by including the handle, which begins with @. However, you should avoid beginning a tweet with the @-symbol, because only people who follow both accounts will be able to see the tweet.

- For more advanced users, you can use a third-party app to schedule tweets. See Liz's post on Twitter strategies for details.

- You can reply to your own tweet to create a chain that Twitter will display to your readers.

- Attribution is important. Anytime you share someone else’s blog post, news article, or video, you want to create a tweet that attributes the content to that user.

How to Create a Tweet

Here's an example of a real tweet that Liz created to share a blog post about a Twitter hashtag.

A few weeks ago, Megan Kate Nelson published “#FollowWomenWednesday” on her blog Historista. The post discusses how social media users share content generated by men more often than they share content authored by women. Megan created the hashtag #FollowWomenWednesday as a way to help call attention to this bias. I found this post intriguing and wanted to share it.

When I create a tweet, I use the headline the author created, craft my own headline, state a reaction to the post, or pose a provocative question about the information contained in the post I want to share.

In the above example, I created the following tweet: “What a Great Idea! #FollowWomenWednesday @megankatenelson #Twitterstorians #Acwri http://histry.us/1Nx6TTS.”

The tweet offers my thoughts on the post, Megan’s headline, her Twitter handle, a link to her post, and hashtags for audiences I think might also be interested in her article, i.e. fellow historians (#Twitterstorians) and academic writers (#acwri).

Whenever possible you want to include the Twitter handle of the source or person who created the content (i.e. @megankatenelson, @thejuntoblog). Perform a quick Google Search of “Name of Blogger or Blog Twitter” If the blogger or source does not list their Twitter handle on their blog.

Tweet Anatomy

My tweet for Megan’s article is 108 characters; 81 characters for my note about the blog post and 23 characters for a shortened link to the article. As tweets with images share more often than text-only tweets, I add an image when possible. In the above example, I dragged and dropped the image Megan included in her post onto my desktop and then clicked the “add photos” icon and selected the image to add it to my tweet. My final tweet contains 128 characters.

We hope this post has given you an idea of how Twitter works at the level of an individual tweet. It's a fun way to interact with other people, whether in a professional or personal setting, and once you're comfortable with the format writing tweets comes much more naturally. ___________________________

[1] If you prefer, you can also sign-up for a URL link shortening service like bit.ly. The advantage to a service like bit.ly is you can track how many times people clicked on the link you shared. Additionally, you can purchase a custom short URL of 8-10 characters and use it as your shortened URL. For example, Liz purchased a custom short URL so all the links she tweets look something like this: http://histry.us/1234abc

[2] Research shows 100 characters to be the ideal length for a tweet. Additionally, some third-party Twitter apps still add users’ handles and ‘RT’ before your original tweet when they retweet you. Leaving at least 10 characters free should ensure that these third-party apps will tweet you whole message when retweeted.