Have you heard of the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon? It's also known as the frequency or recency illusion. It's the phenomenon when you hear or see something unusual and then hear and notice that something repeatedly.

Last week, I noticed that the earliest histories of the American Revolution virtually omitted the Articles of Confederation. Now, I see the omission of the Articles from nearly every place where I would expect to read and find more information about them, like the National Archives' website.[1]

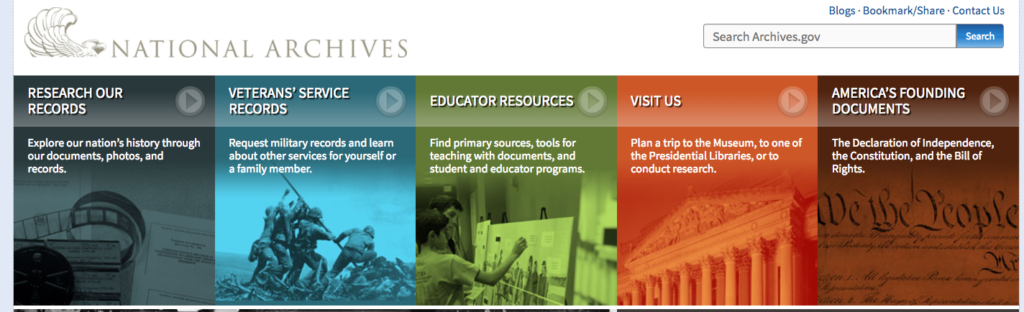

The National Archives holds, conserves, and preserves the founding documents of the United States. When you visit its website, a menu bar at the top of the homepage prominently displays a link to "America's Founding Documents."

Click the link and you will find pictures for and links to the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

The Articles of Confederation is conspicuously absent from the page.[2] In fact, it isn't even a sidebar or bottom-page link away. In this digital representation of "America's Founding Documents," the Articles of Confederation doesn't exist.

The National Archives houses the original, signed copy of the Articles of Confederation. But to find its digital copy, you have to search for it. And the first link you will find, "Welcome to OurDocuments.gov," takes you to a completely different website, which has a far inferior display and web view for documents compared to the Archives' "America's Founding Documents" page.[3]

Archives and History

Archives shape the way we view and interpret history. It's something Jennifer Morgan and Peter Drummey reminded me of during our conversations for the "Doing History: How Historians Work" podcast series and something Karin Wulf talks about in her tweets and blog posts.

The National Archives plays a large role in how we view our nation's written record and what we view as historically important in that record. According to its interpretation, the Articles of Confederation is not a significant document. Therefore the document is hard to find on the National Archives' website--a casual browser would not find it--and the Archives has omitted it from the digital pantheon it created to highlight "America's Founding Documents."[4]

Of course, I disagree with the National Archives.

The Articles of Confederation is one of "America's Founding Documents." In fact, it shares the same lineage as the three documents the National Archives includes within its "Charters of Freedom."

The "America's Founding Documents" Family Tree

The Second Continental Congress agreed to draft articles of confederation on the same day it moved to draft a declaration to declare the colonies' independence from Great Britain.[5]

The fact that the Articles of Confederation placed too much sovereignty in the states caused the Constitutional Convention to convene and draft a new constitution in 1787. The Articles of Confederation directly informed the Constitution of 1787.

The Articles of Confederation also informed Madison's Bill of Rights. For example, Article 2 of the Articles of Confederation states that "Each State retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States, in Congress assembled."[6]

Amendment X of the Bill of Rights: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people."[7]

Project Direction

The ultimate goal of my research into the drafting and ratification of the Articles of Confederation is to produce a multimedia/multi-platform book. In the poetic words of Robert Frost, I have "miles to go before I sleep/And miles to go before I sleep"; I am years away from realizing this goal.[8]

One of the mistakes I made with my dissertation was I waited too long to start writing. Therefore, I'm thinking about writing an article. I have so much research to conduct for this project. Pursuing an article would both direct the directions I go in my research and ensure that I start writing sooner rather than later.

I have two article projects in mind. One article would explore the omission of the Articles of Confederation from histories of the American Revolution. I imagine the article would investigate the early histories of the American Revolution, why the Articles do not fit neatly within those nationalist interpretations of American history, and how the historiography of the Revolution has rarely looked back at the Articles since those early histories.

The second article would be to explore the settlement of the boundary between New York and Massachusetts. The article would explore issues over western land, cultural differences, and how Article 9 of the Articles of Confederation operated. I've wanted to write this article since grad school and I already have a fair amount of the research for it in my files. But I'm not sure I should write it. The article would deal with issues that affected the drafting and ratification of the Articles of Confederation, but it's not a piece I see fitting within a multimedia/multi-platform book focused on how the Second Continental Congress drafted and ratified the Articles.

Notes

[1] Alan Taylor's American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804, is one place I expected to find the Articles of Confederation mentioned and it appeared. Taylor devoted three pages (pages 337-339) to summarizing the Articles and the challenges the Second Congress experienced in drafting and ratifying them.

[2] The Articles of Confederation are also absent from the National Archives online gift shop. For the record, I would purchase a facsimile of the Articles to hang on my wall if one existed.

[3] A bit more searching and you will find the National Archives' wonderful high-resolution images of the signed copy of the Articles of Confederation.

[4] The National Archives also omits the Articles of Confederation from its physical pantheon to the United States' founding documents: the Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom.

[5] Richard Henry Lee's Resolution, June 7, 1776.

[6] It's important to note the importance of Article 2. It appears after Article 1, which states "The Stile of this confederacy shall be, "The United States of America." Transcript of the Articles of Confederation, OurDocuments.Gov.

[7] U.S. National Archives, "The Bill of Rights: A Transcription."

[8] Robert Frost, "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening"