Do you consider yourself an academic or a public historian?

How do you bridge public and academic history?

Do you consider yourself an academic or a public historian?

How do you bridge public and academic history?

I get asked these questions quite often. People ask via e-mail messages and when we meet in-person at seminars and conferences.

In this post, you will discover how I work in both the academic and public history disciplines.

Two Disciplines, One Historian

The simple answer to how I work in both academic and public history: I am a historian.

Intellectually, I am an interdisciplinary historian. I trained as an academic because I wanted to better understand how historians produce historical knowledge and learn how I could participate in this process.

I also have a bit of training as a public historian. I worked as a seasonal interpretive ranger for the Boston National Historical Park for five years (2001-2005). In this role, I witnessed the “David McCullough Phenomenon”: The ability to generate interest in and create advocates for history through the effective communication of history.

The challenge of trying to adapt the "McCullough Phenomenon" for scholarly history fascinates me.

My interest in the entire process of history, from knowledge creation through knowledge dissemination, means I must work in both historical disciplines. I would be dissatisfied intellectually if I had to choose between parts of the process.

4 Ways I Navigate the Worlds of Academic and Public History

1. Network. I network a lot. I attend seminars and conferences about both academic and public history. I engage fellow #Twitterstorians on Twitter, and I network through e-mail; never underestimate the power of a thoughtful reply.

Of all the networking techniques I engage in, attending seminars and conferences is the most powerful way to cultivate relationships with colleagues because interactions happen face-to-face. Additionally, seminars and conferences offer fantastic opportunities to stay abreast of new historical research and interpretive techniques.

The best way to become a part of the academic and public history communities is to know what is going on within the disciplines and to interact with your peers.

2. Participation. I participate in the processes of both history disciplines.

As an academic historian, I produce scholarship and participate in peer review. I research historical questions, analyze and interpret evidence, and I write up my findings for academic journals and (hopefully soon) book publication. I also present my work at conferences.

As a public historian, I interpret scholarly history for non-specialist or public audiences. I distill both important historical research and the historical process and convey it in blog posts, newspaper and magazine articles, and through podcast episodes. I also volunteer at public history organizations when time permits.

3. Education. I try to keep up with scholarship and happenings in both academic and public history.

At present, I subscribe to 6 different journals: The William and Mary Quarterly, Journal of the Early American Republic, Early American Studies, The Public Historian, Journal of American History, and American Historical Review.

Honestly, I lack the time to read all of these journals, but at the very least I read the table of contents for each issue and skim articles that look intriguing or helpful.

Although I am behind in reading journal articles, I am fairly up-to-date with the book historiography for early America. The interview-driven format of Ben Franklin's World ensures that I read at least one history book per week.

I also read a fair number of history blogs each morning by individual historians, historical organizations, and mainstream media.

Knowing the literature of your field, and what is going on within the disciplines, will help you learn about and become a part of the professional communities. Knowing what is going on will also help you network and participate in conversations at your next conference or seminar.

4. Combine Interests. My public history project combines my interest in academic and public history. Ben Franklin’s World is both a public and academic history communications project.

Ben Franklin's World is where I grapple and engage with the challenge of history communication. Each episode represents an attempt to answer: How can I convey history and the historical process in a way that will appeal to a public audience? I want each episode to reveal the importance of history and historians’ work.

Concluding Thoughts

I am not sure if my four techniques will work for everyone, but this is how I bridge the disciplines.

A Note of Caution: If you have the same interdisciplinary historical inclinations that I have, you may find it difficult to find a job with an institution or organization. It has been my experience that both academic and public history organizations want their faculty and staff to focus on one aspect of the discipline. This is why I created my own job.

With that said, both disciplines are changing. In the future, we may see academic training include aspects of public history and public history training include aspects of academic history. It’s an exciting time to be a historian regardless of whether you prefer one side of the discipline to the other or, like me, enjoy them both.

Of late, several professors have inquired whether I offer, or have considered offering, semester-long internships at

Of late, several professors have inquired whether I offer, or have considered offering, semester-long internships at

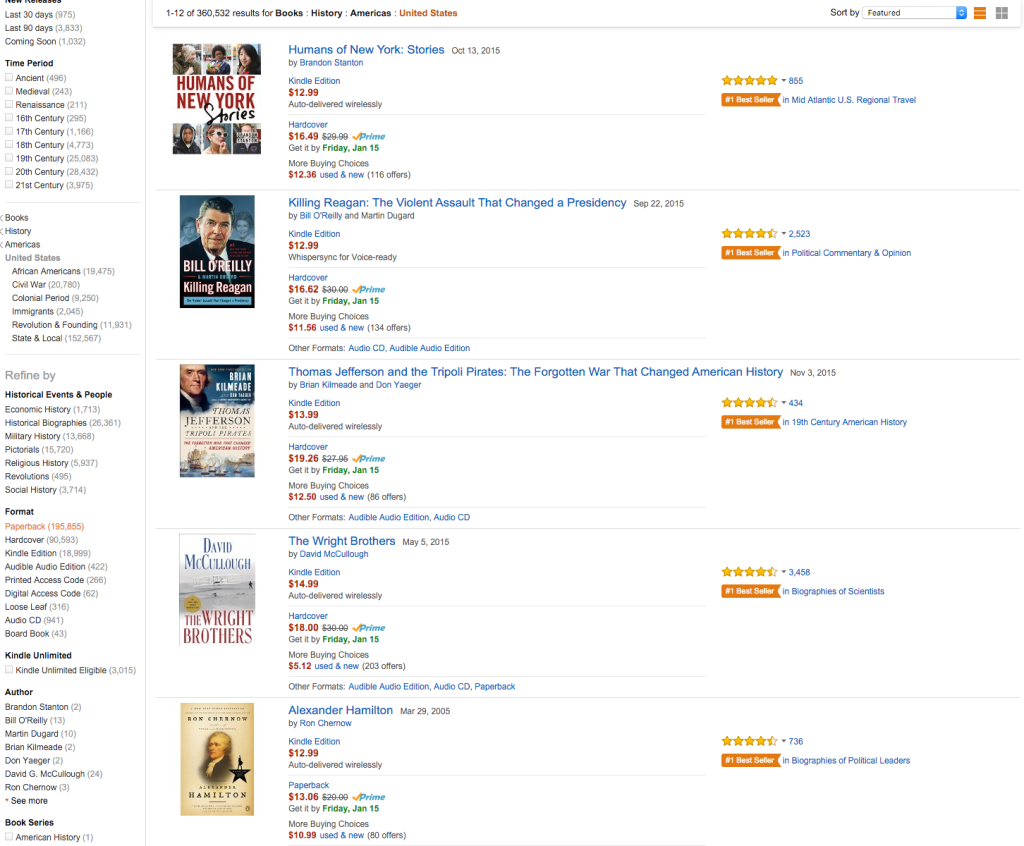

What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for

What makes popular history books "popular?"

Over the last few months, I have read several popular history books for