The 2016 election cycle has been difficult. Not only does it have me worried about the future, it's presenting me with unexpected editorial headaches.

Since April, I've had to consider what to do about guest references to Donald Trump in Ben Franklin's World interviews. Mentions of Trump occurred sporadically until the Republican National Convention. Since the RNC, I've been confronted with decisions about whether to leave these references in episodes or edit them out on a near weekly basis.

The 2016 election cycle has been difficult. Not only does it have me worried about the future, it's presenting me with unexpected editorial headaches.

Since April, I've had to consider what to do about guest references to Donald Trump in Ben Franklin's World interviews. Mentions of Trump occurred sporadically until the Republican National Convention. Since the RNC, I've been confronted with decisions about whether to leave these references in episodes or edit them out on a near weekly basis.

What To Do About Trump?

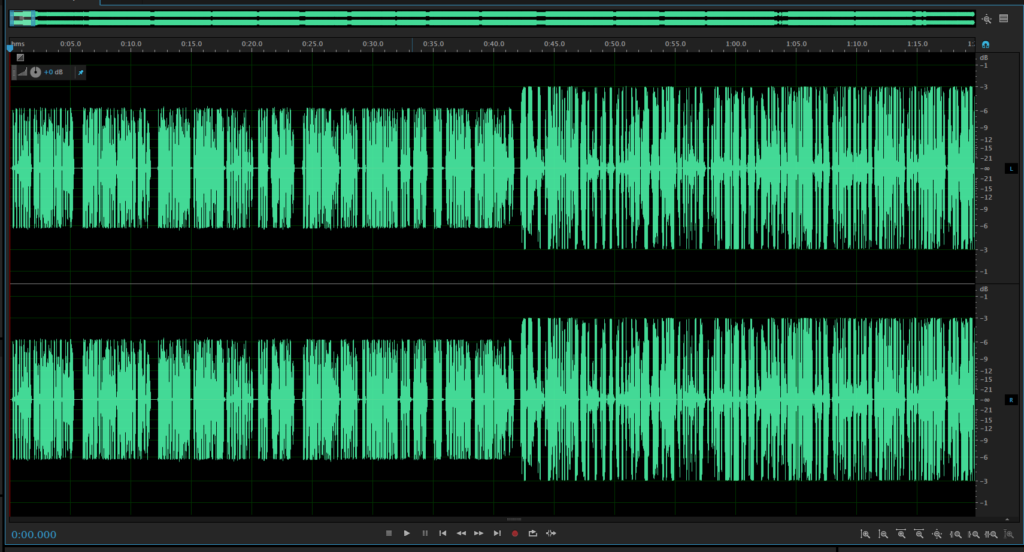

I don't make editorial decisions lightly. When I edit each episode, I listen for the flow of the conversation and what I can do to improve it. Most of the time that involves removing verbal ticks, pauses, and breath sounds. Other times editing involves cutting tangents that don't add to the larger point of the episode. Sometimes it means moving answers to follow-up questions into previous answers so listeners have the context they need to follow what's being said and enjoy the episode.

I don't consider it my job to edit ideas. After all, part of the mission of Ben Franklin's World is to present and make available different ideas about early American history.[1] So, I figuratively sweat over each Trump reference and whether I should leave it in or take it out.

Thus far, all mentions of Trump have conveyed frustration and anger with Trump's politics and many Americans' positive reception of them. All references have sounded spontaneous and gratuitous. I sympathize with my guests. I find Donald Trump’s political views terrifying and I do think historians should do more to speak out against him. With that said, I have cut all anti-Trump statements from conversations I’ve posted through Ben Franklin’s World.

Why?

The primary goal of Ben Franklin’s World is to create wide public awareness about early American history and the work of professional historians. I can’t create this awareness if listeners stop listening. Surveys and interactions with BFWorld listeners reveal that its audience spans the spectrum of the political, cultural, and ethnic diversity of the United States. As such, I've chosen to keep Ben Franklin's World as non-partisan as possible.

However, non-partisan doesn't mean that the show couldn't discuss present-day politics and viewpoints. I believe there is a constructive way guests could bring up and discuss present-day politics without alienating listeners. This way involves historians doing what they do best: approaching and commenting upon modern-day politics from a historical viewpoint.

Guests would need to approach their modern-day political positions on Donald Trump, and Hillary Clinton, from historical standpoints if they wanted those views to air on Ben Franklin's World.

Approaching the Present from the Past: A Fictional Example

To give a broad and fictional example, say a guest comes on the podcast to discuss a book or exhibit about early American immigration. Over the course of our conversation, the guest discusses how their research on colonial Boston reveals that there was a a mass influx of immigrants from Germany, Ireland, Scotland, and Portugal around 1750. With this wave of immigrants came Jews, free blacks, and a large number of Catholics (I’m making this up).

After discussing why these immigrants came to Boston around 1750, the guest discloses the findings of their detailed study into the settlement patterns of those immigrants: The immigrants didn’t settle in enclaves, they settled in equal proportion around the city. The guest explains the significance of this finding: members of the different religious and ethnic immigrant groups intermixed with native-born Bostonians, and vice versa, every day.

Our fictional guest goes on to relate how this intermixing created cultural, religious, and racial tensions that made both new and old Bostonians uncomfortable. However, the need to keep their community united in the face of French imperial threats, meant that the Bostonians used x, y, and z methods to overcome their discord. These methods demonstrated to native-born Bostonians that the diverse immigrants who had settled within their community were assets, not liabilities.

The guest closes by discussing why the colonial Bostonians’ realization is fascinating. They muse about how Americans are still grappling with similar questions about immigration and immigrants today:

“Hillary Clinton wants to create a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants who work to support the United States and their local communities. Donald Trump wants to deport all immigrants regardless of whether or not they have become valuable and productive community members. These modern-day positions make me wonder what would happen if we tried some variation of the colonial Bostonians’ methods for overcoming religious, cultural, and racial tension because if Boston had deported all the immigrants who arrived around 1750, there’s evidence to suggest that the French would have besieged and conquered the city."

The above example is fictitious, but it illustrates how historians could comment upon modern-day politics in a productive way. The fake guest provided listeners with a historical case study and raised ideas about how the past speaks to the present. Their answer invites listeners to wonder what would have happened if colonial Bostonians had deported the immigrants in their city: What would a French Boston have meant for the American Revolution? Would the Revolution have still happened? Would some of the colonial solutions this historian found for overcoming difference work in our own society? Are immigrants really bad for society?

Our fictional historian did not state their political viewpoint. They alluded to it. And they never made a partisan political statement such as “Trump is crazy” or “Hillary is nuts,” statements that would have caused many listeners to stop listening. The fake historian also invited listeners to think about ways the past speaks to the present without telling them what to think. Not all listeners will change their minds as a result of the thoughts and questions the historian raised, but some may, and they will change their minds because the historian included them in a productive thought exercise.

If historians want to make a point about Donald Trump or Hillary Clinton that I would keep in a Ben Franklin’s World episode, they would need to make it in conjunction with historical and factual points. Their statements must add value to the conversation and to how the larger historical point we’re discussing relates to the present.

Historians in the Media

I offer my thoughts on this contentious issue because I believe they are valuable to historians’ broader interactions with media. If you want to influence the election, you need to consider and know the audience of the media outlet you are addressing.

If you are a guest on a political show with a largely partisan audience, consider taking a partisan tact because it’s likely expected. If the outlet you're speaking on has little or nothing to do with modern-day politics, consider moderating and more subtly presenting your points by leading with history. If you are unsure about the audience you'll be speaking to and with, ask your contact at the outlet.

Knowing your audience will enable you to speak to them, not at them. When you speak to your audience (which means you have considered who they are and what they think), you are more likely to find it receptive to the points you are making for and with them.

[1] In offering different viewpoints about the early American past, I interview, edit, and air the ideas of guests I disagree with. Regardless of whether I agree or disagree with a guest's ideas, I try to edit each episode with a sense of detachment and with original context in mind so even historians I disagree with make their points as clearly and as accurately as possible for listeners.

Since January 2016, I have been traveling across the United States speaking about history, podcasting, and digital media at conferences, events, and interviews.

The experience has revealed that people have 3 key questions for me:

Since January 2016, I have been traveling across the United States speaking about history, podcasting, and digital media at conferences, events, and interviews.

The experience has revealed that people have 3 key questions for me: It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with

It’s August and I’ve somehow found myself with 7, straight weeks at home. It’s the first time I’ve been home for a full month this year. (Hence why this blog has been a bit of a ghost town.)

Since January, I’ve been on a type of “history podcast tour.” Historians & history lovers have become fascinated with  On March 3, 2016, I explored the idea of whether it makes sense to create a

On March 3, 2016, I explored the idea of whether it makes sense to create a  Podcasts are hot right now.

Podcasts are hot right now. At

At