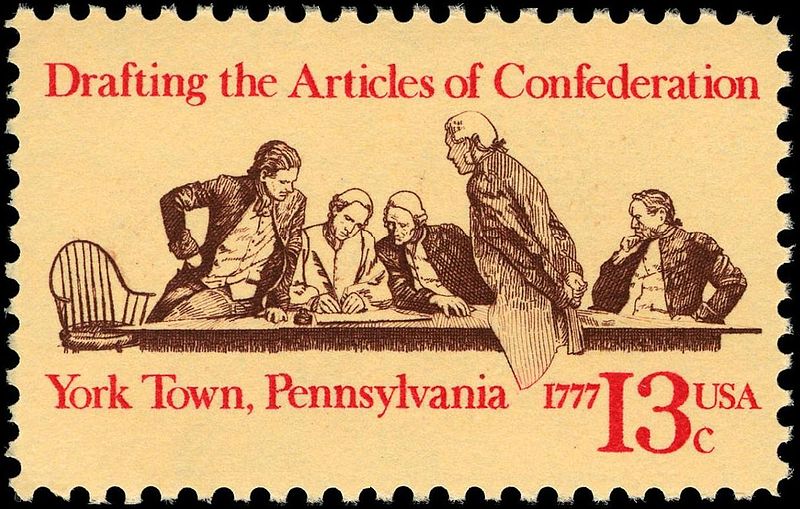

Have you ever wondered why journalists-turned-historians tend to sell more books than professionally-trained historians?

A couple of years ago, I took a writing course about how to write more effective beginnings with Michelle Seaton, a journalist. In a passing comment, Seaton mentioned that all authors need to think about how readers want to learn about the story the writer wants to tell.

Have you ever wondered why journalists-turned-historians tend to sell more books than professionally-trained historians?

A couple of years ago, I took a writing course about how to write more effective beginnings with Michelle Seaton, a journalist. In a passing comment, Seaton mentioned that all authors need to think about how readers want to learn about the story the writer wants to tell.

This comment stuck with me. History books written by journalists tend to be more popular than those written by professionally-trained historians because journalists write them to reveal history in a way that readers want to discover more about it.

In contrast, professionally-trained historians tend to write books that emphasize argument. Historians present the main topic of their book in a way that supports the case they are trying to make. Our books tend to be more about argument than story.

Since this revelation, I have tried to learn more about how professionally-trained historians can tell better stories and still make important historical points that advance our understanding of history.

In this post, you will discover how an article I read on vacation imparts more insight into how journalists-turned-historians write about history.

Bermuda

Tim and I passed our vacation with a roundtrip cruise from Boston to Bermuda. We spent most of the vacation at sea, which allowed us to disconnect from e-mail and the internet.

Tim and I passed our vacation with a roundtrip cruise from Boston to Bermuda. We spent most of the vacation at sea, which allowed us to disconnect from e-mail and the internet.

This glorious 7-day period of respite allowed me to catch up on a lot of reading that I have wanted to do for pleasure.

I read 2 books (a post on [simpleazon-link asin="0393351394" locale="us"]The Book of Negroes[/simpleazon-link] by Lawrence Hill is forthcoming) and articles in approximately 40 different magazines. Articles ranged in subject and came from some of my favorite periodicals: The Week, The Atlantic, The New Yorker, Mindful, Yoga Journal, AHA Perspectives on History, The Writer, and Writer’s Digest.

In the May 2014 issue of The Writer, the “Writing Essentials” segment contained an interview with Mitchell Zuckoff, a journalist and professor of journalism who has authored two World War II-period history books: [simpleazon-link asin="0061988359" locale="us"]Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure, and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II[/simpleazon-link] (2011) and [simpleazon-link asin="0062133403" locale="us"]Frozen in Time: An Epic Story of Survival and a Modern Quest for Lost Heroes of World War II[/simpleazon-link] (2013). Both achieved status as New York Times best sellers.

In the May 2014 issue of The Writer, the “Writing Essentials” segment contained an interview with Mitchell Zuckoff, a journalist and professor of journalism who has authored two World War II-period history books: [simpleazon-link asin="0061988359" locale="us"]Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure, and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II[/simpleazon-link] (2011) and [simpleazon-link asin="0062133403" locale="us"]Frozen in Time: An Epic Story of Survival and a Modern Quest for Lost Heroes of World War II[/simpleazon-link] (2013). Both achieved status as New York Times best sellers.

Writing Like a Journalist

Allison Futterman’s article, “Steps to Believability: Mitchell Zuckoff offers tips on working with research and creating narrative,” investigates Zuckoff’s writing process.

Zuckoff writes using a 3-step process that most historians will find familiar.

Step 1: Identify Topic

Zuckoff identifies a topic before he writes. In the case of both of his history books, Zuckoff wanted to write about World War II. “A self-described ‘newspaper nerd,’ Zuckoff spent countless hours reading newspapers from 1939 to 1945” looking for “the right story that had yet to be told."

Once Zuckoff thinks he has found the “right story,” he conducts “research to see if there is a critical mass” to sustain a book-length project. Like many professionally-trained historians, Zuckoff spends countless hours seeking out information from primary and secondary sources. “By the time Zuckoff starts writing, he has completed 85 to 90 percent of the research.” He completes the remaining 10-15 percent of his research as he writes and discovers holes in his story.

Zuckoff does not confine his research to the historical record. Arctic weather played an important role in the events covered in Frozen in Time. Zuckoff wanted to convey some of what the survivors of the plane crash experienced so he researched the psychological effects people experience when confronted with difficult physical conditions. This research, combined with the survivors’ first-hand accounts, helped him bring the survivors’ experience to life for his readers.

Step 2: Write

Zuckoff wants the people he writes about to “leave an indelible impression” on his readers. To this end, he writes about his topic as a story.

Zuckoff strives “to cultivate a connection between his reader and the material.” He creates this connection using two techniques.

First, Zuckoff does not create dialog. Like professionally-trained historians, he uses quotes from “actual people” in the historical record. By integrating what people really said into his story, Zuckoff fosters “clear development of each character,” which brings “even greater realism” to his work.

Second, Zuckoff writes as authentically as possible. He accomplishes this by remaining true to the historical record and by traveling to the places he writes about so he can place himself in the physical context of his story.

Zuckoff believes that visiting the places you write about and standing on the same “dirt” that your main historical figures once stood on allows a writer to bring an “even greater realism to their work."

Step 3: Revise

Once Zuckoff has drafted his narrative, he revises. Zuckoff offered two revision techniques.

First, Zuckoff reads all of his writing out loud; “read each chapter, then the whole manuscript.” He believes that reading out loud will help you see what research you should keep, which you should omit, and where you need to  use better language and tell a better story; “if you read your book aloud and perform it, you will find places where syntax is twisted or it drags or you’ve gone into a black hole."

use better language and tell a better story; “if you read your book aloud and perform it, you will find places where syntax is twisted or it drags or you’ve gone into a black hole."

Second, Zuckoff treats his research-intensive writing as a process. He concedes that “research does not morph itself into fascinating prose.” Zuckoff polishes his writing “again and again until it feels like you’re [the reader and writer] there” in the historical moment.

As a process, Zuckoff admits that research-intensive writing can be overwhelming. He suggests that we “treat it as a process and understand that as many times as [we] do it, it’s always intimidating. It’s daunting, but it’s one step after another."

Conclusion

For many historians, myself included, thinking about how your readers want to learn about the historical person or episode you want to write about can seem like the most daunting challenge of all. How do we write the history we care so deeply about in a way that will resonate with our readers?

What I found most interesting about this short interview with Michael Zuckoff is that writing for our readers is not rocket science. In fact, in describing his process Zuckoff revealed that he uses many of the tools in the professional historians’ toolbox to write his New York Times best sellers.

What I found most interesting about this short interview with Michael Zuckoff is that writing for our readers is not rocket science. In fact, in describing his process Zuckoff revealed that he uses many of the tools in the professional historians’ toolbox to write his New York Times best sellers.

I took away two important ideas that may help professional historians write better history books.

First, we should write about people as much as possible. Most readers connect best with history when they can relate to and live vicariously through other people. Perhaps this is why nearly all fiction books focus on characters.

Second, just as journalists-turned-historians and historical fiction writers reach into the professional historians’ toolbox to write their books, professional historians should reach into the toolboxes of journalists and fiction writers when we write our books.

Zuckoff approaches the main figures in his stories just as a fiction writer treats their protagonist. He accumulates as many details as he can about the people central to his story. He adds to these historical details by conducting interdisciplinary research and by making the effort to experience the environments and places his subjects encountered. All of this knowledge allows him to write about the people of the past as though they were alive.

What Do You Think?

What techniques do you use to write the best books possible?

You know you've made it as an academic blogger when a senior scholar reads one of your blog posts and expands upon it on their blog. This happened to me last week, when "Historiann" Ann M. Little read "How to Write for Your Readers" and offered a follow-up post.

You know you've made it as an academic blogger when a senior scholar reads one of your blog posts and expands upon it on their blog. This happened to me last week, when "Historiann" Ann M. Little read "How to Write for Your Readers" and offered a follow-up post.